1914: The Union of South Africa's Fatal Year

Quote from Steve on June 5, 2025, 5:52 pmImperial Occupation, European War, Internment, Censorship, Invasion, Republican Rebellion .... and Schism

Steve Hannath with permission from Hugh Amoore RDPSA.

In September 2024 Hugh Amoore RDPSA gave an inspirational Zoom presentation to the South African Collectors’ Society on the subject of ‘Internment in South Africa during WW1’. Those who did not see it missed something special. This article on the major events of 1914 has grown out of Hugh’s Zoom deeply impressive presentation.

The October 2024 issue of SACS's 'The Springbok' includes a full report on that Zoom meeting. Rather than duplicate the report again I decided to combine the material which Hugh supplied to SACS with additional items of my own and other SAPC members in order to underline the pivotal events of 1914 whose consequences shaped much of ‘White South African’ politics for my post-WW2 generation.

Circa 1916. General Louis Botha, Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, 1910 - 1919.

Boer Warrior, Statesman, Empire Loyalist, the Most Hated Man in Republican Afrikanerdom.

Botha's campaign in GSWA was largely a South African one in which he favoured mounted Boer commandos.

He gave Britain its first victory of the war. It was the only 'British' campaign of WW1 not run by British Staff officers.

Cigarette silk (1 of 61), 'General Botha', BDV Cigarettes, (Godfrey Phillips Pty Ltd, Great Britain, 1914-1918).

For an article on the GSWA campaign, see SWA: 1914 - 1923. The Union Land Grab.

If you have material that can expand this article to illustrate the social, political and postal developments in South Africa during WW1, please send scans and your comments to me for my consideration. If suitable I will include them here. In particular, I am looking for items that cover the internment of Enemy Aliens and the withdrawal of the Imperial Garrison after the outbreak of hostilities in Europe. (As a British dominion South Africa entered World War I automatically on 4th August 1914 when Britain declared war on Germany and its allies. South Africa officially declared its support for the war after a divisive Parliamentary debate on 14th September 1914.)

I am also looking for items that will illustrate South Africa's the outburst of riotous public disorder known as ‘Germanophobia’ and, of course, more material on the Invasion of GSWA and also the Republican Rebellion. These events split the Afrikaner nation (Afr. 'die Broedertwis'. the quarrel between brothers) and led to a long period of Afrikaner Nationalist republican agitation and rule in which SA's ad hoc segregation was formaliseed into a political policy known as Apartheid. But that's another story not to be covered here!

Contact Us:

To contact us about this article and or to submit scans, please email:Steve Hannath <editor@southafricanphilatelyclub.com>

This article is more history than one on stamps and covers which I use extensively for the purposes of illustration. To satisfy those philatelists and postal historians with a need for postage rates and routes I start with a brief description of the rates of the time as they were applied to the items illustrated below. The article starts with the South African backround politics leading up to the events of 1914. This article will be in about 8 -10 parts as I am limited to five images per post. It will take a similar number of says to complete.

Postage Rates of the WW1 Internment Period: 1914 – 1919

Under the Hague and UPU (Universal Postal Union) Conventions of 1907 mail from servicemen, POWs and Internees was free of charge. Registered and parcel post mail was treated differently by some countries who were signatories to the conventions. All international mail went by ship (surface mail) as no airmail service existed at the time.

Between 1910 to 1919 the postage rate in the Union of South Africa and SWA once conquered remained much without change. The domestic mail rate on a standard sealed letter was a 1d up to a ½ ounce or a part thereof, a postcard a ½d. Overseas letters to Britain and the Empire were a 1d per ½ ounce and 2½d to foreign destinations (like Germany or the USA). In the Union a Registered letter cost an internee 4d while the normal additional cost of standard postage was free.

Imperial Occupation, European War, Internment, Censorship, Invasion, Republican Rebellion .... and Schism

Steve Hannath with permission from Hugh Amoore RDPSA.

In September 2024 Hugh Amoore RDPSA gave an inspirational Zoom presentation to the South African Collectors’ Society on the subject of ‘Internment in South Africa during WW1’. Those who did not see it missed something special. This article on the major events of 1914 has grown out of Hugh’s Zoom deeply impressive presentation.

The October 2024 issue of SACS's 'The Springbok' includes a full report on that Zoom meeting. Rather than duplicate the report again I decided to combine the material which Hugh supplied to SACS with additional items of my own and other SAPC members in order to underline the pivotal events of 1914 whose consequences shaped much of ‘White South African’ politics for my post-WW2 generation.

Circa 1916. General Louis Botha, Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, 1910 - 1919.

Boer Warrior, Statesman, Empire Loyalist, the Most Hated Man in Republican Afrikanerdom.

Botha's campaign in GSWA was largely a South African one in which he favoured mounted Boer commandos.

He gave Britain its first victory of the war. It was the only 'British' campaign of WW1 not run by British Staff officers.

Cigarette silk (1 of 61), 'General Botha', BDV Cigarettes, (Godfrey Phillips Pty Ltd, Great Britain, 1914-1918).

For an article on the GSWA campaign, see SWA: 1914 - 1923. The Union Land Grab.

If you have material that can expand this article to illustrate the social, political and postal developments in South Africa during WW1, please send scans and your comments to me for my consideration. If suitable I will include them here. In particular, I am looking for items that cover the internment of Enemy Aliens and the withdrawal of the Imperial Garrison after the outbreak of hostilities in Europe. (As a British dominion South Africa entered World War I automatically on 4th August 1914 when Britain declared war on Germany and its allies. South Africa officially declared its support for the war after a divisive Parliamentary debate on 14th September 1914.)

I am also looking for items that will illustrate South Africa's the outburst of riotous public disorder known as ‘Germanophobia’ and, of course, more material on the Invasion of GSWA and also the Republican Rebellion. These events split the Afrikaner nation (Afr. 'die Broedertwis'. the quarrel between brothers) and led to a long period of Afrikaner Nationalist republican agitation and rule in which SA's ad hoc segregation was formaliseed into a political policy known as Apartheid. But that's another story not to be covered here!

Contact Us:

To contact us about this article and or to submit scans, please email:

Steve Hannath <editor@southafricanphilatelyclub.com>

This article is more history than one on stamps and covers which I use extensively for the purposes of illustration. To satisfy those philatelists and postal historians with a need for postage rates and routes I start with a brief description of the rates of the time as they were applied to the items illustrated below. The article starts with the South African backround politics leading up to the events of 1914. This article will be in about 8 -10 parts as I am limited to five images per post. It will take a similar number of says to complete.

Postage Rates of the WW1 Internment Period: 1914 – 1919

Under the Hague and UPU (Universal Postal Union) Conventions of 1907 mail from servicemen, POWs and Internees was free of charge. Registered and parcel post mail was treated differently by some countries who were signatories to the conventions. All international mail went by ship (surface mail) as no airmail service existed at the time.

Between 1910 to 1919 the postage rate in the Union of South Africa and SWA once conquered remained much without change. The domestic mail rate on a standard sealed letter was a 1d up to a ½ ounce or a part thereof, a postcard a ½d. Overseas letters to Britain and the Empire were a 1d per ½ ounce and 2½d to foreign destinations (like Germany or the USA). In the Union a Registered letter cost an internee 4d while the normal additional cost of standard postage was free.

Quote from Steve on June 6, 2025, 12:51 pm1902 - The War is Over (.... for some)

The defeated ‘Boer’ Republican forces surrendered on 31st May 1902. The SAW (South African War), one started by the Boers as a pre-emptory strike against a much superior foe, ended in the horror of a holocaust. Many surrendered Boers who had been imprisoned overseas found they had neither homes nor family to return to. This was the result of the British Army's scorched earth policies - the destruction of farms, homesteads, even some small rural towns, as well as cattle and livestock - and the forced removal of Boer 'refugees' to concentration camps where appalling conditions and indifferent treatment led to a death among children that peaked at 433 / 1000.

Following the “Khaki Election” of 1900, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Liberal MP and leader of the Liberal Party, met Emily Hobhouse, a British anti-war activist. She bought the plight of the incarcerated ‘Boer’ and African ‘refugess’ to the British public;s attention. Campbell-Bannerman was so shocked by what Hobhouse told him of the conditions in the concentration camps that he described them as ‘methods of barbarism’ in a speech to the National Reform Union in June 1901. As a result, for many Boers defeat by and peace with the British was hard to swallow. The bitterness they felt became a cornerstone of Afrikaner Nationalist Republicanism.

Victory in the SAW saw Britain achieve its long-held imperial goal for southern Africa, the unification of its British colonies of the Cape and Natal with the defeated ‘Boer’ republics of the OFS (Orange Free State) and ZAR (South African Republic aka ‘Transvaal). In order to maintain Pax Brittanica while strong-arming the reluctant ‘Boers’ into accepting the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Britain retained a large and powerful army, the Imperial Garrison, in South Africa, from 1902 - 1914. Victory in the SAW left the country’s English jingoists cock-a-hoop. There was now no obstacle to the British running the country for the benfit of capital.

For many, this was the natural order of things at a time when God was thought to be an Englishman. As a result, the Boers had to be made to speak English in school, the courts and the civil service. The imperial hubris that the English expressed after the Boer surrender was soon tempered by recognition that the ‘Boers’ were the largest European group in the country. Politically English-speakers would have to play second fiddle in any democratic Boer’ ‘tiekiedraai’. (Afr. a fast folk dance that turns on a tight circle). If Britain’s long-term goal of unification was to be achieved the defeated ‘Dutchmen’, ‘Japies’ and ‘back-velders’, had to be accomodated and brought on-side.

The defeated ‘Boer leaders made it clear that there could be no negotiations with Britain if Black South Africans were given political rights. For its part Britain felt that Black South Africans were yet not ready to run a rapidly industrialising country whose mineral wealth its Empire had fought a hugely expensive war to acquire. ('Steal' was the word many Boers used.) When the negotiations finally concluded with agreement Britain granted political power in the Union of South Africa to ‘Europeans Only’. The objections of Black South Africans were brushed aside as Britain concentrated the finding right men to lead ‘Boer’ and Brit in its new Imperial dominion, the Union of South Africa, now the land of 'White South Africans'.

The British found their 'main man' in the previous Commander of the defeated ZAR Forces, General Louis Botha, the victor of Colenso and Spion Kop in Natal. He was to be ably assisted by General Jan Smuts, previously the ZAR's State Attorney, an intellectual who could have had a stellar career within Britain's Temple legal fraternity had he chosen to remain in the UK after graduating from Christ College, Cambridge. Together these two Afrikaner men would share an unwavering loyalty to the British Empire which they saw as a shield behind which White South Africa would prosper across southern Africa. For them the sky was the limit in terms of what was possible.

Their first and biggest mistake was to assume that the ex-Boer commanders that they appointed to high office in the Union of South Africa government and its nascent UDF (Union Defence Force) shared their new-found enthusiasm for the British Empire. Many did not. They still grieved for their lost republics and their 'volk' (Afr. folk, kin), some 26,000 women, children and old men dead in British concentration camps. Indeed, when Smuts propagandised German atrocities against 'kith and kin' in Europe during the "Rape of Belgium" in 1914, General Christiaan Beyers, the Commandant-General of the UDF, replied on the eve of the Republican rebellion"we (the Boers) have forgiven but not forgotten all the barbarities comitted in our own country during the war."

More to come. Watch this space.......

1902 - The War is Over (.... for some)

The defeated ‘Boer’ Republican forces surrendered on 31st May 1902. The SAW (South African War), one started by the Boers as a pre-emptory strike against a much superior foe, ended in the horror of a holocaust. Many surrendered Boers who had been imprisoned overseas found they had neither homes nor family to return to. This was the result of the British Army's scorched earth policies - the destruction of farms, homesteads, even some small rural towns, as well as cattle and livestock - and the forced removal of Boer 'refugees' to concentration camps where appalling conditions and indifferent treatment led to a death among children that peaked at 433 / 1000.

Following the “Khaki Election” of 1900, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Liberal MP and leader of the Liberal Party, met Emily Hobhouse, a British anti-war activist. She bought the plight of the incarcerated ‘Boer’ and African ‘refugess’ to the British public;s attention. Campbell-Bannerman was so shocked by what Hobhouse told him of the conditions in the concentration camps that he described them as ‘methods of barbarism’ in a speech to the National Reform Union in June 1901. As a result, for many Boers defeat by and peace with the British was hard to swallow. The bitterness they felt became a cornerstone of Afrikaner Nationalist Republicanism.

Victory in the SAW saw Britain achieve its long-held imperial goal for southern Africa, the unification of its British colonies of the Cape and Natal with the defeated ‘Boer’ republics of the OFS (Orange Free State) and ZAR (South African Republic aka ‘Transvaal). In order to maintain Pax Brittanica while strong-arming the reluctant ‘Boers’ into accepting the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Britain retained a large and powerful army, the Imperial Garrison, in South Africa, from 1902 - 1914. Victory in the SAW left the country’s English jingoists cock-a-hoop. There was now no obstacle to the British running the country for the benfit of capital.

For many, this was the natural order of things at a time when God was thought to be an Englishman. As a result, the Boers had to be made to speak English in school, the courts and the civil service. The imperial hubris that the English expressed after the Boer surrender was soon tempered by recognition that the ‘Boers’ were the largest European group in the country. Politically English-speakers would have to play second fiddle in any democratic Boer’ ‘tiekiedraai’. (Afr. a fast folk dance that turns on a tight circle). If Britain’s long-term goal of unification was to be achieved the defeated ‘Dutchmen’, ‘Japies’ and ‘back-velders’, had to be accomodated and brought on-side.

The defeated ‘Boer leaders made it clear that there could be no negotiations with Britain if Black South Africans were given political rights. For its part Britain felt that Black South Africans were yet not ready to run a rapidly industrialising country whose mineral wealth its Empire had fought a hugely expensive war to acquire. ('Steal' was the word many Boers used.) When the negotiations finally concluded with agreement Britain granted political power in the Union of South Africa to ‘Europeans Only’. The objections of Black South Africans were brushed aside as Britain concentrated the finding right men to lead ‘Boer’ and Brit in its new Imperial dominion, the Union of South Africa, now the land of 'White South Africans'.

The British found their 'main man' in the previous Commander of the defeated ZAR Forces, General Louis Botha, the victor of Colenso and Spion Kop in Natal. He was to be ably assisted by General Jan Smuts, previously the ZAR's State Attorney, an intellectual who could have had a stellar career within Britain's Temple legal fraternity had he chosen to remain in the UK after graduating from Christ College, Cambridge. Together these two Afrikaner men would share an unwavering loyalty to the British Empire which they saw as a shield behind which White South Africa would prosper across southern Africa. For them the sky was the limit in terms of what was possible.

Their first and biggest mistake was to assume that the ex-Boer commanders that they appointed to high office in the Union of South Africa government and its nascent UDF (Union Defence Force) shared their new-found enthusiasm for the British Empire. Many did not. They still grieved for their lost republics and their 'volk' (Afr. folk, kin), some 26,000 women, children and old men dead in British concentration camps. Indeed, when Smuts propagandised German atrocities against 'kith and kin' in Europe during the "Rape of Belgium" in 1914, General Christiaan Beyers, the Commandant-General of the UDF, replied on the eve of the Republican rebellion"we (the Boers) have forgiven but not forgotten all the barbarities comitted in our own country during the war."

More to come. Watch this space.......

Quote from Steve on November 17, 2025, 7:06 pmGeneral Louis Botha played a pivotal, conciliatory role in the political transition that led to the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. As former Boer commander who had fought fiercely against the British during the South African War, he had earned Britain's respect. To Britain's surprise and delight Botha emerged from the conflict as a statesman committed to healing divisions and securing a stable constitutional settlement between Boer and Brit. His leadership mattered because he held credibility with two constituencies that distrusted one another: the victorious British imperial authorities and the defeated, resentful Boer population of the former republics.

1902. The War is Over. The Empire has Won. Afrikaner Recriminations Begin.

Botha understood that long-term security for Afrikaners required political accommodation rather than renewed confrontation. He used his growing relationship with British leaders to obtain moderate terms for self-government in the Transvaal (1907) and, later, to shape a broader union acceptable to both sides. His skill lay in persuading British officials that former Boer fighters could be trusted partners if given a real political stake, while simultaneously convincing sceptical Boer communities that constitutional cooperation offered greater benefits than isolation or resistance. He achieved this among his own people while they remained in the shadow of a bitter war.

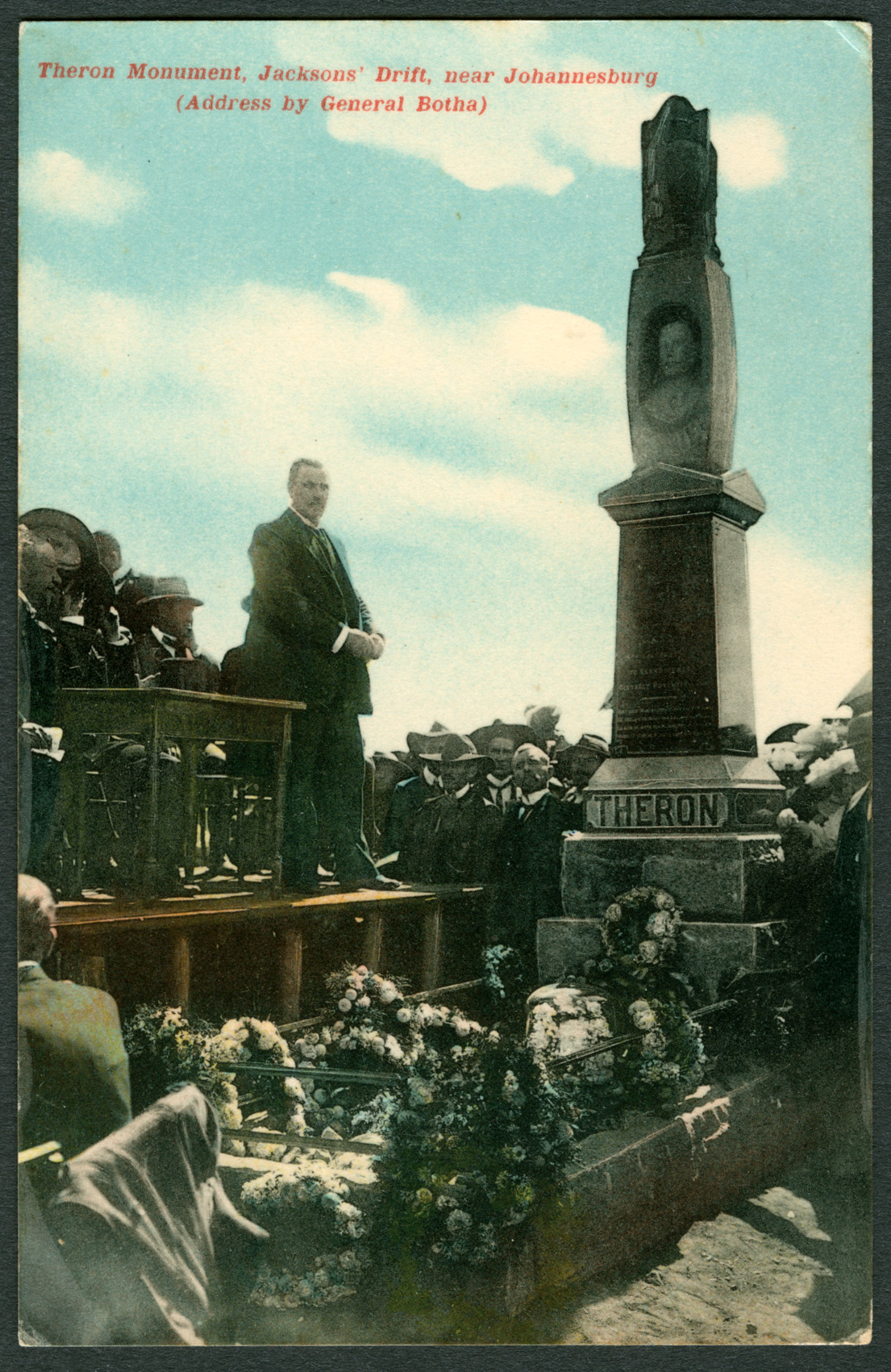

1907. Political Theatre. Keeping the Faith with the Boer Volk by commemorating one of their Heros.

General Louis Botha addresses the unveiling of the Danie Theron memorial on 28th December 1907.

Botha and General Jan Smuts jointly unveiled the Danie Theron gravestone near PotchefstroomHowever, Botha’s vision of reconciliation was almost entirely confined to relations between White South Africans. When it came to Black South Africans, he aligned with the prevailing White political consensus that the franchise should remain racially restricted. Botha opposed extending the non-racial Cape franchise model to the rest of the Union and supported compromises that ensured Black South Africans would be largely disenfranchised under the new constitution. His arguments framed political exclusion as necessary for “stability” and “racial order,” helping cement a constitutional structure that entrenched White political dominance and laid the groundwork for later segregationist policies. As Britain largely mistrusted Black South Africans, it supported Botha's racist proposals.

A key source of Botha’s effectiveness was his close partnership with General Jan Smuts. Smuts brought formidable intellect, strategic vision, and legal mastery to the Union project. Together, they crafted a pragmatic argument for unification, one of economic coherence, coordinated infrastructure and a political framework strong enough to manage internal tensions. Smuts handled much of the constitutional design at the National Convention while Botha worked to unify divided Afrikaner opinion and maintain British confidence. In the end, the Union of South Africa reflected Botha’s juggling act: conciliatory toward White factions, exclusionary toward Black South Africans, and ultimately shaped by compromises that prioritized White unity over broader democratic rights.

More to come. Watch this space.......

General Louis Botha played a pivotal, conciliatory role in the political transition that led to the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. As former Boer commander who had fought fiercely against the British during the South African War, he had earned Britain's respect. To Britain's surprise and delight Botha emerged from the conflict as a statesman committed to healing divisions and securing a stable constitutional settlement between Boer and Brit. His leadership mattered because he held credibility with two constituencies that distrusted one another: the victorious British imperial authorities and the defeated, resentful Boer population of the former republics.

1902. The War is Over. The Empire has Won. Afrikaner Recriminations Begin.

Botha understood that long-term security for Afrikaners required political accommodation rather than renewed confrontation. He used his growing relationship with British leaders to obtain moderate terms for self-government in the Transvaal (1907) and, later, to shape a broader union acceptable to both sides. His skill lay in persuading British officials that former Boer fighters could be trusted partners if given a real political stake, while simultaneously convincing sceptical Boer communities that constitutional cooperation offered greater benefits than isolation or resistance. He achieved this among his own people while they remained in the shadow of a bitter war.

1907. Political Theatre. Keeping the Faith with the Boer Volk by commemorating one of their Heros.

General Louis Botha addresses the unveiling of the Danie Theron memorial on 28th December 1907.

Botha and General Jan Smuts jointly unveiled the Danie Theron gravestone near Potchefstroom

However, Botha’s vision of reconciliation was almost entirely confined to relations between White South Africans. When it came to Black South Africans, he aligned with the prevailing White political consensus that the franchise should remain racially restricted. Botha opposed extending the non-racial Cape franchise model to the rest of the Union and supported compromises that ensured Black South Africans would be largely disenfranchised under the new constitution. His arguments framed political exclusion as necessary for “stability” and “racial order,” helping cement a constitutional structure that entrenched White political dominance and laid the groundwork for later segregationist policies. As Britain largely mistrusted Black South Africans, it supported Botha's racist proposals.

A key source of Botha’s effectiveness was his close partnership with General Jan Smuts. Smuts brought formidable intellect, strategic vision, and legal mastery to the Union project. Together, they crafted a pragmatic argument for unification, one of economic coherence, coordinated infrastructure and a political framework strong enough to manage internal tensions. Smuts handled much of the constitutional design at the National Convention while Botha worked to unify divided Afrikaner opinion and maintain British confidence. In the end, the Union of South Africa reflected Botha’s juggling act: conciliatory toward White factions, exclusionary toward Black South Africans, and ultimately shaped by compromises that prioritized White unity over broader democratic rights.

More to come. Watch this space.......

Quote from Steve on November 18, 2025, 4:31 pmLouis Botha - His Pre-War Years

Louis Botha was born into a modest Boer farming family on 27th September 1862, near Greytown in the British colony of Natal. His parents had been children on the Great Trek of 1835. The eighth of thirteen children, he was seven when his family moved to a farm near Vrede in the Orange Free State. His childhood was shaped in a multi-racial frontier environment that comprised long days helping on the farm, limited formal schooling and a great deal of practical responsibility from an early age. Though his education was irregular and limited, Botha was naturally bright, observant, and confident. His early years taught him a mix of resilience and pragmatism which when coupled with his sympathy for ordinary people became the characteristics of his later South African leadership.

As a young man, he developed a taste for adventure and, like all Boers, (Afr. farmers), land. In 1884 he served as a volunteer under Commandant Lukas Meyer in the successful campaign to restore Dinuzulu,, son of the Zulu chief Cetshwayo, to the Zulu throne. In appreciation of the services of the Boer volunteers, Dinuzulu granted the Boers a large tract of land on the southeastern Transvaal border. As a prominent younger leader Botha was made a member of the commission which divided the land given to the 'Dinizulu Volunteers'. Botha received the farm Waterval, near Vryheid, soon to be the headquarters of the New Republic, a bold attempt by Boer settlers to carve out a small, independent state in northern Zululand. It would struggle for recognition and stability.

Circa 1900. Boer Generals Louis Botha and Lukas Meyer and their wives.

Photos taken of both men show them wearing these uniforms in Natal and at the fall of Pretoria.

This is excellent work by Tinus le Roux. I will try to obtain more of his work which brings history to life.During the period of the New Republic's creation Botha met and married Annie Emmett. Her support and social skill helped ground his political and military career. Annie Emmett (sometimes spelled Emmet in contemporary documents) came from an English-speaking settler family in Natal. Her upbringing and home language were English. She was considered culturally and socially a “Natal colonial” rather than a Boer. She later became fluent in Dutch/Afrikaans despitee English being her home language. Annie's nature and background made her a calm, diplomatic bridge between the increasingly divided English and Boer language groups. She would prove to be of great use to the combatants of both sides who sought peace and reconciliation during and after the South African War.

Botha met Annie after her family moved into the same frontier world in which he was already active. Her father, John Emmett, was an English-speaking farmer and trader in northern Natal who frequently interacted with Boer families across the border that divided Natal colonists from ZAR (Transvaal) burghers. Botha was introduced to Annie through mutual acquaintances in the Lucks Meyer circle. After they married in Natal in 1884 the New Republic was established. Botha was rising in influence and Annie’s English-speaking background gave him social flexibility on a frontier where language and culture normally formed boundaries. The New Republic was absorbed into the South African Republic (ZAR) in 1888. Despite its demise Botha’s role in its formation had built him a reputation as a capable, steady, and fair-minded leader.

Some suggest the “Emmett/Emmet” surname raises the question of a family link to Robert Emmet, the Irish nationalist executed in 1803 for treason. (I have been guilty of conflating this link between Annie and more especially her brother Cheere with the Irish nationalist hero, in part because at the end of the Battle of Colenso Botha gave Cheere, his brother-n-law, the significant honour of bringing in the ten guns captured from Colonel Long. Cheere would become a Boer general and remain in in the field with Botha until the end of the war.) No documented genealogical connection exists to associate Annie and Cheere with Robert Emmet who died childless. While he had siblings, the Emmet/Emmett families who settled in southern Africa trace their roots to unrelated Irish or Anglo-Irish lines that emigrated decades later. Historians of Botha’s life generally refard it as a coincidental surname overlap.

The Bothas later settled on the farm Onverwacht near Vryheid, where Botha built a comfortable household and became active in local affairs. Botha and Annie had eleven children together, six daughters and five sons, between 1886 to 1904. The exact ordering of births varies slightly in different sources. Birth years are approximate because some early records were lost or inconsistently recorded during the ZAR period and also subject to the destruction of the South African War. Annie managed the large Botha household mostly on her own during Botha’s long absences in the South African War and later while he was in political office. Several of their children were still quite young when Botha became Prime Minister in 1910,

Circa 1902. Cinderella Label showing General Botha in uniform.

The SA Collectors Society website suggests that this is from the German SWA Campaign.

Perhaps. But given the uniform and age of Botha the image more likely shows him in the SAW of 1899 - 1902.

However, it could be a WW1 label using an earlier image of him.Botha's work as a farmer, field-cornet, and community representative brought him deeper into the political life of the ZAR. By the 1890s he had emerged as a respected figure, practical, moderate, and trusted by his neighbors. This was well before he became publicly known on the wider international stage. Long before the South African War, Botha's life had forged him with the qualities of frontier resilience, diplomatic instinct and a steady, persuasive leadership style. The coming war would make him a formidable military commander..

Louis Botha - His Pre-War Years

Louis Botha was born into a modest Boer farming family on 27th September 1862, near Greytown in the British colony of Natal. His parents had been children on the Great Trek of 1835. The eighth of thirteen children, he was seven when his family moved to a farm near Vrede in the Orange Free State. His childhood was shaped in a multi-racial frontier environment that comprised long days helping on the farm, limited formal schooling and a great deal of practical responsibility from an early age. Though his education was irregular and limited, Botha was naturally bright, observant, and confident. His early years taught him a mix of resilience and pragmatism which when coupled with his sympathy for ordinary people became the characteristics of his later South African leadership.

As a young man, he developed a taste for adventure and, like all Boers, (Afr. farmers), land. In 1884 he served as a volunteer under Commandant Lukas Meyer in the successful campaign to restore Dinuzulu,, son of the Zulu chief Cetshwayo, to the Zulu throne. In appreciation of the services of the Boer volunteers, Dinuzulu granted the Boers a large tract of land on the southeastern Transvaal border. As a prominent younger leader Botha was made a member of the commission which divided the land given to the 'Dinizulu Volunteers'. Botha received the farm Waterval, near Vryheid, soon to be the headquarters of the New Republic, a bold attempt by Boer settlers to carve out a small, independent state in northern Zululand. It would struggle for recognition and stability.

Circa 1900. Boer Generals Louis Botha and Lukas Meyer and their wives.

Circa 1900. Boer Generals Louis Botha and Lukas Meyer and their wives.

Photos taken of both men show them wearing these uniforms in Natal and at the fall of Pretoria.

This is excellent work by Tinus le Roux. I will try to obtain more of his work which brings history to life.

During the period of the New Republic's creation Botha met and married Annie Emmett. Her support and social skill helped ground his political and military career. Annie Emmett (sometimes spelled Emmet in contemporary documents) came from an English-speaking settler family in Natal. Her upbringing and home language were English. She was considered culturally and socially a “Natal colonial” rather than a Boer. She later became fluent in Dutch/Afrikaans despitee English being her home language. Annie's nature and background made her a calm, diplomatic bridge between the increasingly divided English and Boer language groups. She would prove to be of great use to the combatants of both sides who sought peace and reconciliation during and after the South African War.

Botha met Annie after her family moved into the same frontier world in which he was already active. Her father, John Emmett, was an English-speaking farmer and trader in northern Natal who frequently interacted with Boer families across the border that divided Natal colonists from ZAR (Transvaal) burghers. Botha was introduced to Annie through mutual acquaintances in the Lucks Meyer circle. After they married in Natal in 1884 the New Republic was established. Botha was rising in influence and Annie’s English-speaking background gave him social flexibility on a frontier where language and culture normally formed boundaries. The New Republic was absorbed into the South African Republic (ZAR) in 1888. Despite its demise Botha’s role in its formation had built him a reputation as a capable, steady, and fair-minded leader.

Some suggest the “Emmett/Emmet” surname raises the question of a family link to Robert Emmet, the Irish nationalist executed in 1803 for treason. (I have been guilty of conflating this link between Annie and more especially her brother Cheere with the Irish nationalist hero, in part because at the end of the Battle of Colenso Botha gave Cheere, his brother-n-law, the significant honour of bringing in the ten guns captured from Colonel Long. Cheere would become a Boer general and remain in in the field with Botha until the end of the war.) No documented genealogical connection exists to associate Annie and Cheere with Robert Emmet who died childless. While he had siblings, the Emmet/Emmett families who settled in southern Africa trace their roots to unrelated Irish or Anglo-Irish lines that emigrated decades later. Historians of Botha’s life generally refard it as a coincidental surname overlap.

The Bothas later settled on the farm Onverwacht near Vryheid, where Botha built a comfortable household and became active in local affairs. Botha and Annie had eleven children together, six daughters and five sons, between 1886 to 1904. The exact ordering of births varies slightly in different sources. Birth years are approximate because some early records were lost or inconsistently recorded during the ZAR period and also subject to the destruction of the South African War. Annie managed the large Botha household mostly on her own during Botha’s long absences in the South African War and later while he was in political office. Several of their children were still quite young when Botha became Prime Minister in 1910,

Circa 1902. Cinderella Label showing General Botha in uniform.

The SA Collectors Society website suggests that this is from the German SWA Campaign.

Perhaps. But given the uniform and age of Botha the image more likely shows him in the SAW of 1899 - 1902.

However, it could be a WW1 label using an earlier image of him.

Botha's work as a farmer, field-cornet, and community representative brought him deeper into the political life of the ZAR. By the 1890s he had emerged as a respected figure, practical, moderate, and trusted by his neighbors. This was well before he became publicly known on the wider international stage. Long before the South African War, Botha's life had forged him with the qualities of frontier resilience, diplomatic instinct and a steady, persuasive leadership style. The coming war would make him a formidable military commander..

Quote from Steve on November 21, 2025, 9:33 amSome British Attitudes to the Defeated Boers

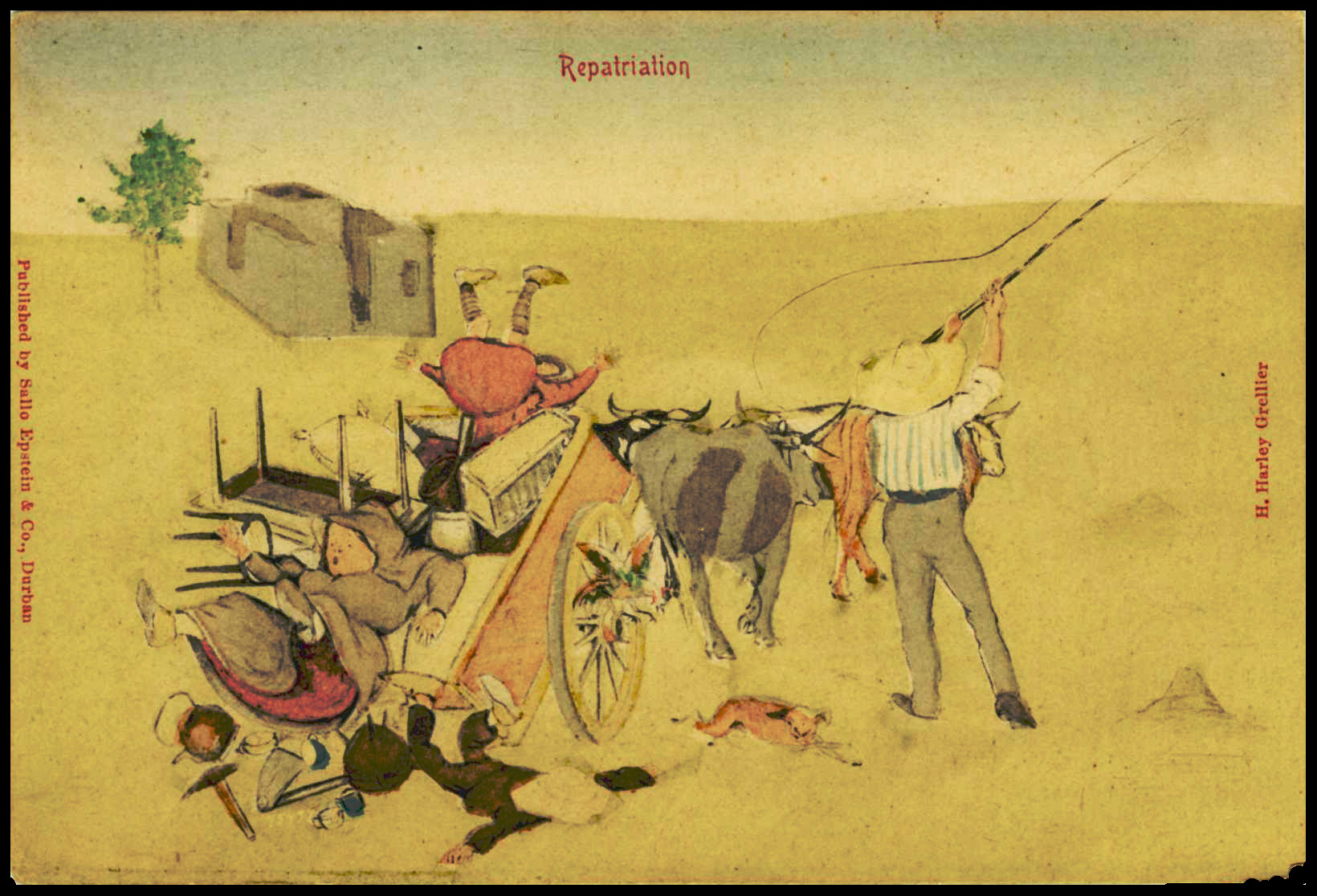

Circa 1902. Postcard. Unused. 'Repatriation'. (Published by Sallo Epstein & Co., Durban. H. Harley Grellier.)

Objects of mirth. A Boer family return to their burned-down farmhouse. The wagon collapses.

The wife, children and meagre possessions are dumped on the veld.In the aftermath of the war and the surrender via the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging, the British subjected the defeated Boers to harsh military laws that resricted movement. All travel required permits. This made it very difficult for the Boers to return to the farms from which they had been evicted and once there to rebuild their homes by purchasing the necessary supplies to do so. The British Army destroyed approximately 30,000 Boer homesteads during the South African War as part of a "scorched earth" policy, the systematic burning of farms and the destruction of crops and livestock. Its aim was to deny Boer commandos the ability to resupply from sympathetic farmers. The restrictions of post-war martial law made life very difficult for the Boers as they attempted to rebuild their farms, initially without financial support, and to reconnect with family. This caused lingering bitterness rather than reconciliation.

Circa 1902. Postcard. Unused. 'The Great Event'. (Published by Sallo Epstein & Co., Durban. H. Harley Grellier.)

"A Boer Woman silencing her children whilst the father signs his name."According to Paul van Zeyl who used this postcard in his 'Dorsland Trekker' display to show one of the reasons why some Boers left South Africa after the end of the war, this postcard refers to the Signing of the Oath of Allegiance that all Boers combatants had to sign before being allowed to return home. This is probably not what is happening here. What it does show is a slick, urbane, well-fed and manicured Englishman requiring the signature of a dishevelled and work-stained semi-literate backveld Boer farmer with the brow of a Neanderthal. This postcard shows the Boers as unsophisticated and stupid. Sallo Epstein's postcards are a wonderful source of paper-based archaeology. Hewre we see the arrogrance at the heart of a British Empire whose central tenet was that God was an Englishman.

This disrespect that the British had for the Boers was a major obstacle that Botha and Smuts had to overcome as they attempted to drag both Boer and Brit along together with them to the altar of marriage within the Union of South Africa. The Boers would bring their own historic resentments and desires for republican rule to the union. The British would largely bring their own smugness in ther grandeur of the Britsh Empire, refined, liberal and virtuous. It was always going to be a delicate juggling act.

Some British Attitudes to the Defeated Boers

Circa 1902. Postcard. Unused. 'Repatriation'. (Published by Sallo Epstein & Co., Durban. H. Harley Grellier.)

Objects of mirth. A Boer family return to their burned-down farmhouse. The wagon collapses.

The wife, children and meagre possessions are dumped on the veld.

In the aftermath of the war and the surrender via the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging, the British subjected the defeated Boers to harsh military laws that resricted movement. All travel required permits. This made it very difficult for the Boers to return to the farms from which they had been evicted and once there to rebuild their homes by purchasing the necessary supplies to do so. The British Army destroyed approximately 30,000 Boer homesteads during the South African War as part of a "scorched earth" policy, the systematic burning of farms and the destruction of crops and livestock. Its aim was to deny Boer commandos the ability to resupply from sympathetic farmers. The restrictions of post-war martial law made life very difficult for the Boers as they attempted to rebuild their farms, initially without financial support, and to reconnect with family. This caused lingering bitterness rather than reconciliation.

Circa 1902. Postcard. Unused. 'The Great Event'. (Published by Sallo Epstein & Co., Durban. H. Harley Grellier.)

"A Boer Woman silencing her children whilst the father signs his name."

According to Paul van Zeyl who used this postcard in his 'Dorsland Trekker' display to show one of the reasons why some Boers left South Africa after the end of the war, this postcard refers to the Signing of the Oath of Allegiance that all Boers combatants had to sign before being allowed to return home. This is probably not what is happening here. What it does show is a slick, urbane, well-fed and manicured Englishman requiring the signature of a dishevelled and work-stained semi-literate backveld Boer farmer with the brow of a Neanderthal. This postcard shows the Boers as unsophisticated and stupid. Sallo Epstein's postcards are a wonderful source of paper-based archaeology. Hewre we see the arrogrance at the heart of a British Empire whose central tenet was that God was an Englishman.

This disrespect that the British had for the Boers was a major obstacle that Botha and Smuts had to overcome as they attempted to drag both Boer and Brit along together with them to the altar of marriage within the Union of South Africa. The Boers would bring their own historic resentments and desires for republican rule to the union. The British would largely bring their own smugness in ther grandeur of the Britsh Empire, refined, liberal and virtuous. It was always going to be a delicate juggling act.