Correspondence - Postal History with Letters

Quote from Steve on October 17, 2025, 4:38 pmOver the years I have bought postal history covers from dealers who never bothered to read their enclosed contents. To them what was important was the quick realisation of some cash from a mediocre cover with stamps showing good but not great postmarks. Its content was the added mystery bonus. While it is satisfying for a collector to find an interesting cover in good condition, a postal historian's delight comes from its rates and routes. For the historian, it is the possibilty of the letter's content to reveal unrecorded social history.

The following unsigned letter is from the correspondence of Percy Horsfall. His letters come up for sale from time to time. He is usually writing to a woman - and she to him. I have always thought she was his wife - but now I am not so sure. Curiously, he has not signed this letter so in truth we do not know categorically that the writer is Percy Horsfall. However, other letters by him exist with the same distinctive handwriting, all also written in German. Add to this his references to his work in government and his membership of the Rand Club and I think it safe to say that this is indeed another letter from Percy Horsfall. But who is the woman he is writing to?

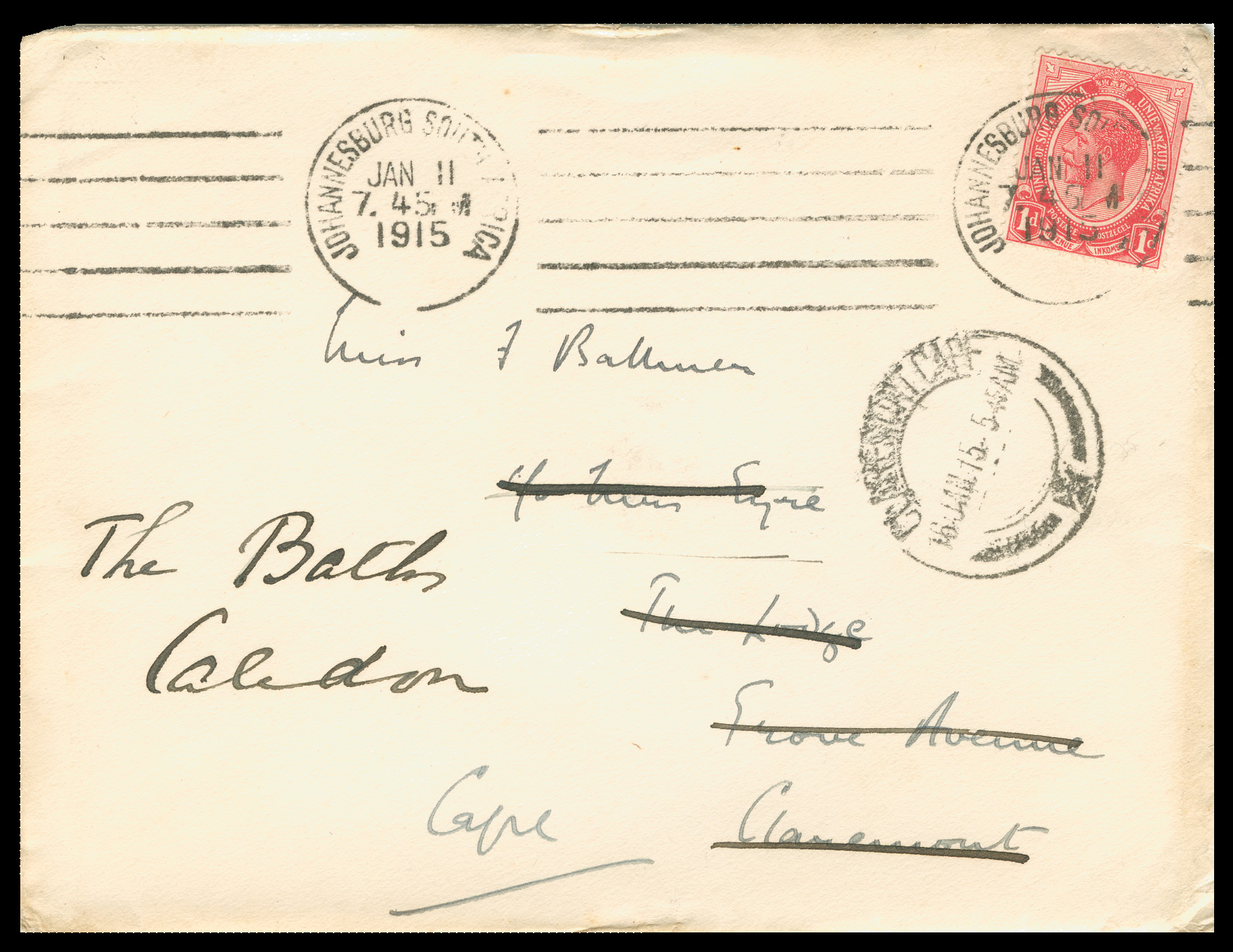

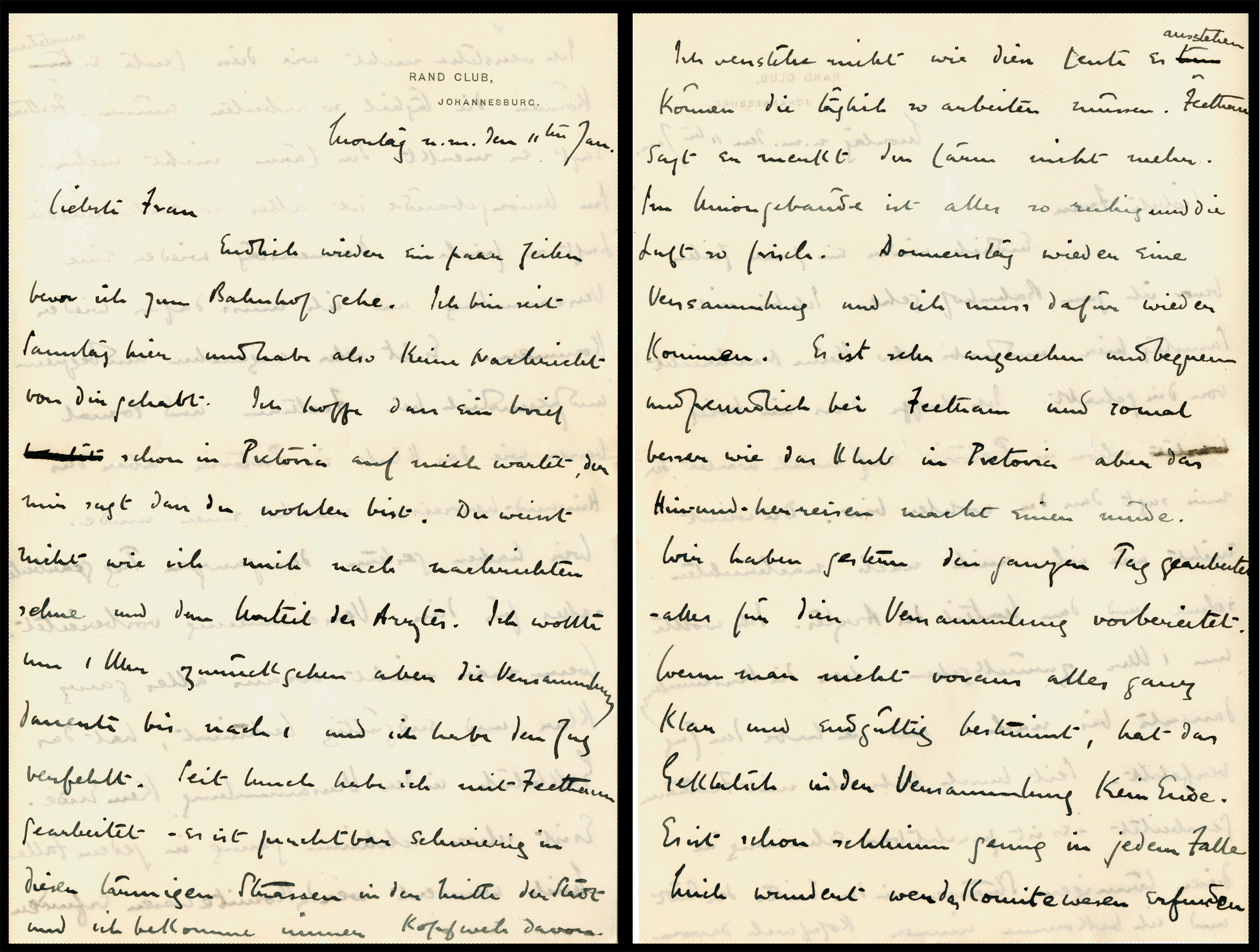

1915. Entire. Rand Club Stationery. Cover from JOHANNESBURG 'JAN 11 1915' to CLAREMONT, CAPE '16 JAN 15'.

1d red King's Head cancelled 5 bar 'JOHANNESBURG SOUTH AFRICA' machine canceller.

Rerouted to "The Baths, Caledon".

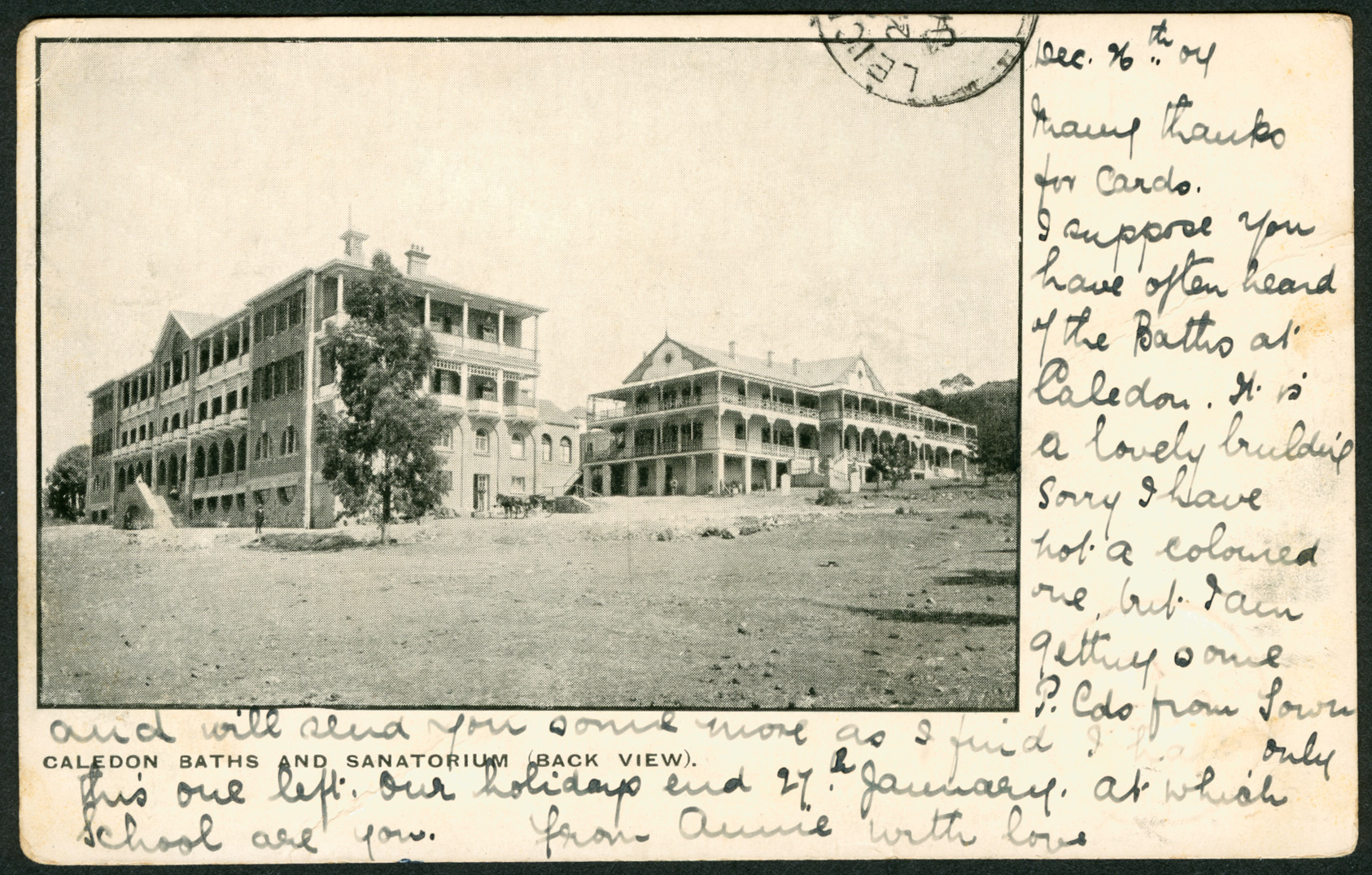

1907. Postcard. 'Caledon Baths and Sanitorium - Back View'.

Percy Horsfall (c. 1879–1920s) was one of Lord Alfred Milner’s so-called “bright young men” — the elite circle of often Oxford-educated administrators and intellectuals who formed the 'Kindergarten', as Milner called them during his time as High Commissioner for South Africa (1897–1905). Educated in England, Horsfall entered the Colonial Service and was posted to South Africa in the wake of the South African War. He became a minor and overlooked part of the administrative apparatus helping to build Britain's new Union of South Africa, established 1910.

While capable and well-connected, Horsfall's letter suggests that he struggled with the dull, bureaucratic atmosphere of colonial life - something reflected in this vivid letter written in 1915 from the Rand Club, Johannesburg. His tone of exile and alienation - he refers to “this desolate land” and its "coarse and unrefined" leaders making him “feel like a wretched dwarf” - shows his distaste for South Africa's colonial social climate. The letter portrays him as a thoughtful, disillusioned man, missing European intellectual life and corresponding affectionately with a woman named Frances, possibly his wife, someone with whom he had previously spent happier times with in France. His reflections on French culture, politics, and the contrast with the colonial world reveal a personality that was both cosmopolitan and restless. Little is recorded about Horsfall after WW1. It is believed he returned to Britain or possibly France. More letters like this survive. They offer a rare insight into the mindset of an imperial servant in exile from his own culture.

Sitting in the Rand Club on Monday, 11th January 1915, Horsfall is writing in German to Miss F 'Baltimer' (?) in Claremont, Cape. He is using the Club's supplied stationery. Presumably Horsfall has been preoccupied with official matters relating to the start of WW1 and the outbreak of the Republican rebellion in South Africa. In exactly one month's time General Louis Botha will assume command of the Northern Force in Swakopmund on February 11, 1915, to lead the second phase of the German South West Africa campaign.

OCR (creating readable text from scan) and translation courtesy of ChatGPT (OpenAI).

Dearest Lady, (possibly Frau or Fran),

At last, a few lines again before I go to the station. I have been here since Saturday and have therefore had no news from you. I hope that a letter is already waiting for me in Pretoria, showing me that you are well. You cannot imagine how much I long for news and for the sound of your voice. I meant to be back by one o’clock, but the meeting went on into the night and I missed the day. Since then, I have been busy with fortifications and offices — it is terribly difficult in these hot streets in the middle of Africa — and I always get headaches from it. You cannot imagine how people can manage to work in this heat.

Feuerstein says he no longer understands life at all. The idea of the Union is too powerful for everyone, and the air so oppressive. On Thursday there will be another meeting, and I shall probably have to come again. It is pleasant enough and understandable during the festivities, especially in the Club at Pretoria, but all this travelling back and forth makes me tired. Yesterday we spent the entire day working or preparing for the meeting. If one has not settled everything clearly and definitively beforehand, one can find no peace during the meeting. One thing is bad enough in any case - I am not surprised when (as our dear friend used to say) “la politique est une chose sérieuse”. (Fr. politics is a serious matter.)

It has now become a main part of our democratic system, within whose autonomy we are supposed to correct the obvious mistakes.

One must look on when one thinks of it. Today I looked through the French newspapers here in the club — Le Livre, La Vie Parisienne, etc. It is terribly funny: you know what they used to be like, but now they are hardly recognizable. Not a spark of wit in the entire paper, no humorous sketches! Everything is about war — depictions of battles, the experiences of English soldiers, heroic tales, descriptions of life during the war in Paris with an indescribable seriousness. No spontaneity anymore, no jokes, hardly any patriotism even — only a sort of duty.I read one story and it was just the same. A lady, young and beautiful, was walking along the boulevard, followed by a well-dressed gentleman of about thirty. He repeatedly tried, unsuccessfully, to speak to her. Finally, she turned around and said: “N’insistez pas, monsieur; qui n’est pas bon pour le Service de la Patrie n’est pas bon pour les dames.” (Fr. Do not insist, sir; he who is not good for the service of the Fatherland is not good for the ladies.) I have read in all the English papers about the immense seriousness of the French, and never believed it. But now I see it is true - and, strangely, I find it rather endearing, for the French have so many charming ways.

The occupations of the old world — they have become for them a kind of rebirth as a nation. Strange; I think of our happy days in France, of our experiences, and of those that are yet to come. Are you happy about that, Frances? It helps me to stay content in these gloomy times and in this desolate land when I think of a more cheerful, more interesting, and richer society in Europe. The leaders here, in their daily life, are neither indifferent to sorrow nor to joy - they are simply coarse and unrefined. One feels here like a wretched dwarf.

Strange, in a few hours I must know how you are and when I may hope to be on my way to you. It is long to wait, but our being together will richly repay all the waiting. Tomorrow again, perhaps.

Take care of yourself, please, and remain loving.

Your faithful one,

A thousand tender kisses.

This illustration, above, comes courtesy of ChatGPT (OpenAI). It reimagines Horsfall’s world: the perspiring civil servant on a sunstruck Johannesburg afternoon, hat in hand, caught between longing and propriety as an elegant woman strolls past outside the Rand Club on Loveday Street.

If anyone else has letters from Percy Horsfall and or his wife, please share them with us.

Over the years I have bought postal history covers from dealers who never bothered to read their enclosed contents. To them what was important was the quick realisation of some cash from a mediocre cover with stamps showing good but not great postmarks. Its content was the added mystery bonus. While it is satisfying for a collector to find an interesting cover in good condition, a postal historian's delight comes from its rates and routes. For the historian, it is the possibilty of the letter's content to reveal unrecorded social history.

The following unsigned letter is from the correspondence of Percy Horsfall. His letters come up for sale from time to time. He is usually writing to a woman - and she to him. I have always thought she was his wife - but now I am not so sure. Curiously, he has not signed this letter so in truth we do not know categorically that the writer is Percy Horsfall. However, other letters by him exist with the same distinctive handwriting, all also written in German. Add to this his references to his work in government and his membership of the Rand Club and I think it safe to say that this is indeed another letter from Percy Horsfall. But who is the woman he is writing to?

1915. Entire. Rand Club Stationery. Cover from JOHANNESBURG 'JAN 11 1915' to CLAREMONT, CAPE '16 JAN 15'.

1d red King's Head cancelled 5 bar 'JOHANNESBURG SOUTH AFRICA' machine canceller.

Rerouted to "The Baths, Caledon".

1907. Postcard. 'Caledon Baths and Sanitorium - Back View'.

Percy Horsfall (c. 1879–1920s) was one of Lord Alfred Milner’s so-called “bright young men” — the elite circle of often Oxford-educated administrators and intellectuals who formed the 'Kindergarten', as Milner called them during his time as High Commissioner for South Africa (1897–1905). Educated in England, Horsfall entered the Colonial Service and was posted to South Africa in the wake of the South African War. He became a minor and overlooked part of the administrative apparatus helping to build Britain's new Union of South Africa, established 1910.

While capable and well-connected, Horsfall's letter suggests that he struggled with the dull, bureaucratic atmosphere of colonial life - something reflected in this vivid letter written in 1915 from the Rand Club, Johannesburg. His tone of exile and alienation - he refers to “this desolate land” and its "coarse and unrefined" leaders making him “feel like a wretched dwarf” - shows his distaste for South Africa's colonial social climate. The letter portrays him as a thoughtful, disillusioned man, missing European intellectual life and corresponding affectionately with a woman named Frances, possibly his wife, someone with whom he had previously spent happier times with in France. His reflections on French culture, politics, and the contrast with the colonial world reveal a personality that was both cosmopolitan and restless. Little is recorded about Horsfall after WW1. It is believed he returned to Britain or possibly France. More letters like this survive. They offer a rare insight into the mindset of an imperial servant in exile from his own culture.

Sitting in the Rand Club on Monday, 11th January 1915, Horsfall is writing in German to Miss F 'Baltimer' (?) in Claremont, Cape. He is using the Club's supplied stationery. Presumably Horsfall has been preoccupied with official matters relating to the start of WW1 and the outbreak of the Republican rebellion in South Africa. In exactly one month's time General Louis Botha will assume command of the Northern Force in Swakopmund on February 11, 1915, to lead the second phase of the German South West Africa campaign.

OCR (creating readable text from scan) and translation courtesy of ChatGPT (OpenAI).

Dearest Lady, (possibly Frau or Fran),

At last, a few lines again before I go to the station. I have been here since Saturday and have therefore had no news from you. I hope that a letter is already waiting for me in Pretoria, showing me that you are well. You cannot imagine how much I long for news and for the sound of your voice. I meant to be back by one o’clock, but the meeting went on into the night and I missed the day. Since then, I have been busy with fortifications and offices — it is terribly difficult in these hot streets in the middle of Africa — and I always get headaches from it. You cannot imagine how people can manage to work in this heat.

Feuerstein says he no longer understands life at all. The idea of the Union is too powerful for everyone, and the air so oppressive. On Thursday there will be another meeting, and I shall probably have to come again. It is pleasant enough and understandable during the festivities, especially in the Club at Pretoria, but all this travelling back and forth makes me tired. Yesterday we spent the entire day working or preparing for the meeting. If one has not settled everything clearly and definitively beforehand, one can find no peace during the meeting. One thing is bad enough in any case - I am not surprised when (as our dear friend used to say) “la politique est une chose sérieuse”. (Fr. politics is a serious matter.)

It has now become a main part of our democratic system, within whose autonomy we are supposed to correct the obvious mistakes.

One must look on when one thinks of it. Today I looked through the French newspapers here in the club — Le Livre, La Vie Parisienne, etc. It is terribly funny: you know what they used to be like, but now they are hardly recognizable. Not a spark of wit in the entire paper, no humorous sketches! Everything is about war — depictions of battles, the experiences of English soldiers, heroic tales, descriptions of life during the war in Paris with an indescribable seriousness. No spontaneity anymore, no jokes, hardly any patriotism even — only a sort of duty.

I read one story and it was just the same. A lady, young and beautiful, was walking along the boulevard, followed by a well-dressed gentleman of about thirty. He repeatedly tried, unsuccessfully, to speak to her. Finally, she turned around and said: “N’insistez pas, monsieur; qui n’est pas bon pour le Service de la Patrie n’est pas bon pour les dames.” (Fr. Do not insist, sir; he who is not good for the service of the Fatherland is not good for the ladies.) I have read in all the English papers about the immense seriousness of the French, and never believed it. But now I see it is true - and, strangely, I find it rather endearing, for the French have so many charming ways.

The occupations of the old world — they have become for them a kind of rebirth as a nation. Strange; I think of our happy days in France, of our experiences, and of those that are yet to come. Are you happy about that, Frances? It helps me to stay content in these gloomy times and in this desolate land when I think of a more cheerful, more interesting, and richer society in Europe. The leaders here, in their daily life, are neither indifferent to sorrow nor to joy - they are simply coarse and unrefined. One feels here like a wretched dwarf.

Strange, in a few hours I must know how you are and when I may hope to be on my way to you. It is long to wait, but our being together will richly repay all the waiting. Tomorrow again, perhaps.

Take care of yourself, please, and remain loving.

Your faithful one,

A thousand tender kisses.

This illustration, above, comes courtesy of ChatGPT (OpenAI). It reimagines Horsfall’s world: the perspiring civil servant on a sunstruck Johannesburg afternoon, hat in hand, caught between longing and propriety as an elegant woman strolls past outside the Rand Club on Loveday Street.

If anyone else has letters from Percy Horsfall and or his wife, please share them with us.

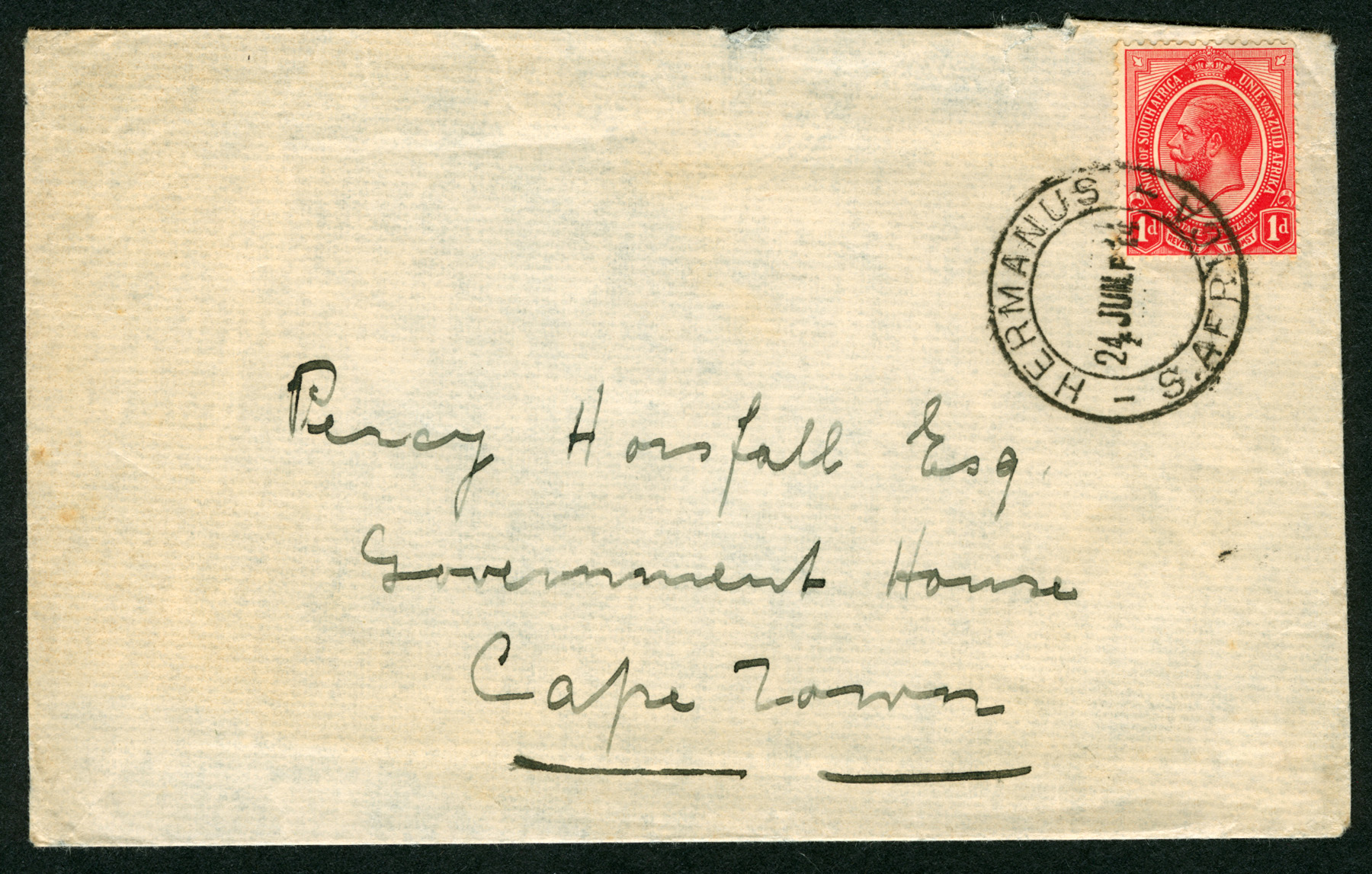

Quote from Steve on October 19, 2025, 1:11 pmHere is a letter written in Hermanus in June 1914 addressed to Percy Horsfall at Government House in Cape Town. The letter is from his well-connected wife. It is intimate and troubled. It suggests love and affection but also regret and misunderstanding. Perhaps all is not well between them. She and Percy are separated, perhaps on account of his work. While both this letter and the preceding one are written in German it appears that the women are possibly different. We will need to find more letters to better understand thir situation.

It is important to note that unlike the preceding letter which was written in January 1915 six months after the start of WW1, the letter below was written in Hermanus some 5 weeks before before the war started. When Great Britain declared war on Germany and its allies on 4th August 1914, South Africa, as a British Dominion, was automatically drawn into the conflict because Great Britain's declaration extended to all of its Empire. The Rebellion in South Africa probably placed great demands on Percy's time, energy and patience.

1914. Cover. HERMANUS '24 JUN 14' to CAPE TOWN.

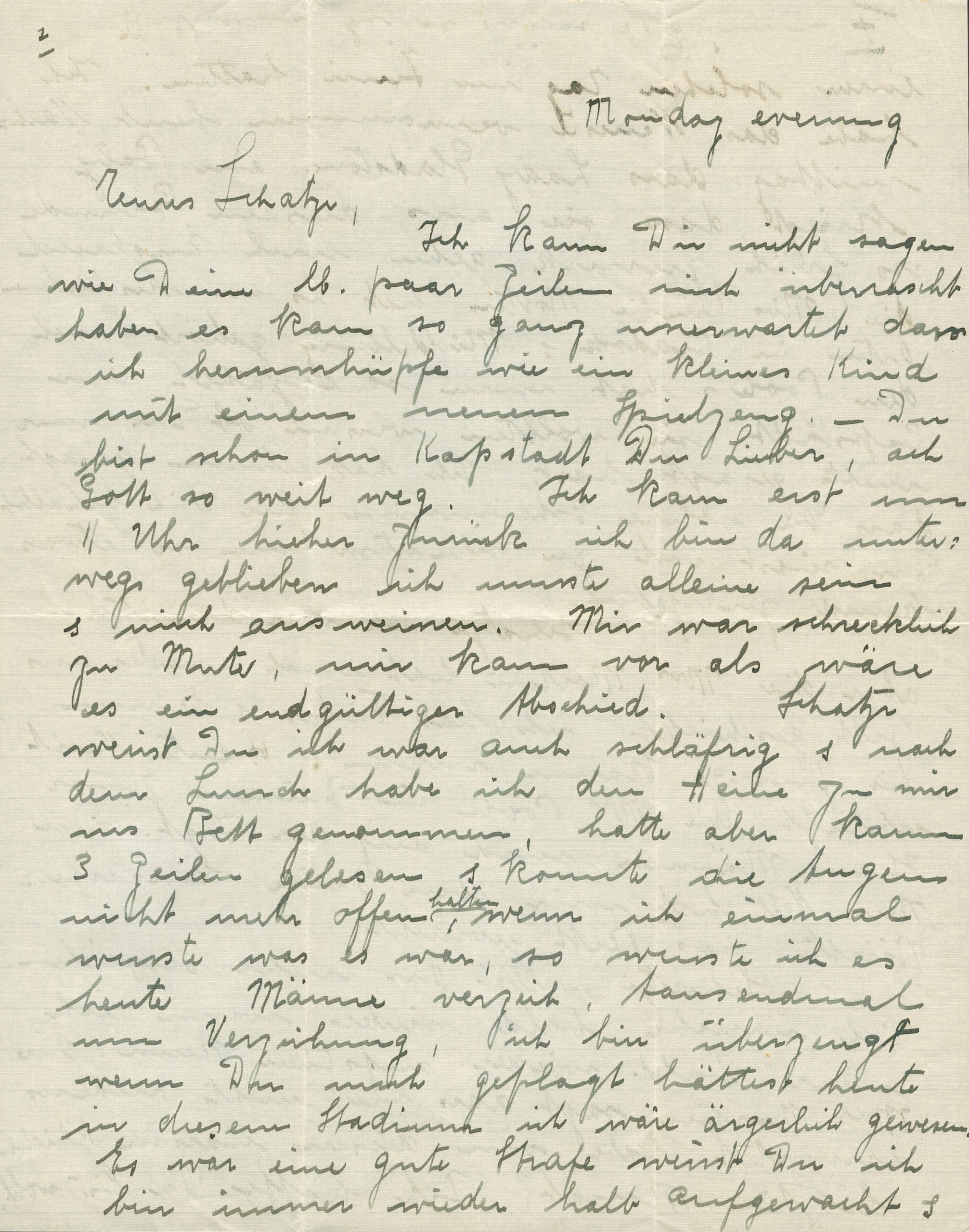

"Monday evening

My darling,

I can’t tell you how surprised I was by your dear few lines — they came so completely unexpectedly that I’ve been skipping around like a little child with a new toy. You’re already in Cape Town, my dear — oh God, so far away.I only got here at 11 o'clock; I had to stay for a while. I had to be alone and cry it out. I felt terrible; it seemed as if it were a final goodbye. Darling, do you think I was sleepy too? After lunch, I took the blanket to bed with me, but I had barely read three lines before I couldn't keep my eyes open any longer. If I ever knew what it was, I knew it today — men, forgive me a thousand times. I’m sure that if you had teased me today, in this condition, I would have been annoyed. It would have been a good punishment if you had — I keep waking up halfway again and I heard your voice, or maybe I was just imagining things. Four times I ran to the window, thinking you had just arrived. Then suddenly came the painful awareness that you were far away, sitting on the train — perhaps cold and uncomfortable. It was strange: every time I half fell asleep, the same vision and noise returned to me.

If God wanted me to be punished, then so be it — and I am glad. Darling, please tell me that you forgive me. I know now that you were very sleepy and might have wanted to scold / hit* me.

They're just telling me no mail will go out tomorrow. What am I to do now? I hope you understand. I’m afraid that if I try to telephone, it will take a long time again. I’d rather arrange it with you — let’s say Friday, darling, between half past eleven and half past twelve, all right? I'm sitting by the fire, the Pooles are here and their daughter has arrived. The Pooles picked up Lister and his wife in Hawston. Darling, if you only knew how much I long for you — it’s simply unbearable. Yes, next time it must be for longer. I’ll write again tomorrow, darling. I want to go to bed early and think of you.

Adieu.

Affectionately.

I hope you sleep well tonight and that you haven’t caught a cold.

Many, many kisses.Good morning, my dear man,

I’m lying in bed — it looks as though I’ll stay here all day. It’s so uncomfortable and hot. I wish you could sit here and read to me. There’s a hot wind blowing outside. I’m glad you’re not traveling today. It will probably rain and storm again soon.I have terrible pains — though not yet unwell. I wonder if you're coming to me up Sir Lowry Pass. And whether you’ll be able to look at Danger Point. It was terrible last night. I kept thinking you must somehow appear — but there was not the slightest trace of you, except for the shaving brush still lying in the room next door.

6 p.m.

I've had visitors all day and couldn't write. Now I want to get up and get some fresh air. The heat is unbearable, I can't take it anymore. Everyone here says they've never had such a day in June. I heard the latest news this afternoon. Lady Gladstone is having a baby, and that’s why they’re going back to England so early. Mrs. Emilie Morton apparently heard something about it down in Cradock and Middelburg — and the Pooles were told the same in Cape Town. They wanted to know if you had said anything to me. I told them that you always keep such secrets to yourself — you are far too shy to make such things known.Darling, I was downstairs, but Mrs. Morton sent me back to bed. I have a fever and can hardly move the little one. Mrs. Poole is sleeping in your room tonight. Her men are out hunting. Mrs. Nell just brought me your shaving brush to bed.

Darling, will you forgive me? I'll write again soon, when I can get up again. Mrs. Morton says she expected nothing less from those warm clothes last month. I hope you're well."

Horsfall's wife, the writer of this letter, did not sign it nor put her address on its reverse.

I had both ChatGPT and HandwritingOCR read and convert this letter into an editable text / DOC file. When I converted thier text files from German into English using both ChatGPT and Google Translate there were considerable comparative differences between the two versions. This was very disappointing. Ultimately I compared both translations and edited them to produce my own version.

* With regard to her husband wanting to "scold / hit" her, these are two very different interpretations taken from translation of ChatGPT's and HandwritingOCR' OCR'ed text. I decided to leave both in so as to allow the reader to choose the word that best describes their opinion of this developing domestic drama in Hermanus all those years ago.

Here is a letter written in Hermanus in June 1914 addressed to Percy Horsfall at Government House in Cape Town. The letter is from his well-connected wife. It is intimate and troubled. It suggests love and affection but also regret and misunderstanding. Perhaps all is not well between them. She and Percy are separated, perhaps on account of his work. While both this letter and the preceding one are written in German it appears that the women are possibly different. We will need to find more letters to better understand thir situation.

It is important to note that unlike the preceding letter which was written in January 1915 six months after the start of WW1, the letter below was written in Hermanus some 5 weeks before before the war started. When Great Britain declared war on Germany and its allies on 4th August 1914, South Africa, as a British Dominion, was automatically drawn into the conflict because Great Britain's declaration extended to all of its Empire. The Rebellion in South Africa probably placed great demands on Percy's time, energy and patience.

1914. Cover. HERMANUS '24 JUN 14' to CAPE TOWN.

"Monday evening

My darling,

I can’t tell you how surprised I was by your dear few lines — they came so completely unexpectedly that I’ve been skipping around like a little child with a new toy. You’re already in Cape Town, my dear — oh God, so far away.

I only got here at 11 o'clock; I had to stay for a while. I had to be alone and cry it out. I felt terrible; it seemed as if it were a final goodbye. Darling, do you think I was sleepy too? After lunch, I took the blanket to bed with me, but I had barely read three lines before I couldn't keep my eyes open any longer. If I ever knew what it was, I knew it today — men, forgive me a thousand times. I’m sure that if you had teased me today, in this condition, I would have been annoyed. It would have been a good punishment if you had — I keep waking up halfway again and I heard your voice, or maybe I was just imagining things. Four times I ran to the window, thinking you had just arrived. Then suddenly came the painful awareness that you were far away, sitting on the train — perhaps cold and uncomfortable. It was strange: every time I half fell asleep, the same vision and noise returned to me.

If God wanted me to be punished, then so be it — and I am glad. Darling, please tell me that you forgive me. I know now that you were very sleepy and might have wanted to scold / hit* me.

They're just telling me no mail will go out tomorrow. What am I to do now? I hope you understand. I’m afraid that if I try to telephone, it will take a long time again. I’d rather arrange it with you — let’s say Friday, darling, between half past eleven and half past twelve, all right? I'm sitting by the fire, the Pooles are here and their daughter has arrived. The Pooles picked up Lister and his wife in Hawston. Darling, if you only knew how much I long for you — it’s simply unbearable. Yes, next time it must be for longer. I’ll write again tomorrow, darling. I want to go to bed early and think of you.

Adieu.

Affectionately.

I hope you sleep well tonight and that you haven’t caught a cold.

Many, many kisses.

Good morning, my dear man,

I’m lying in bed — it looks as though I’ll stay here all day. It’s so uncomfortable and hot. I wish you could sit here and read to me. There’s a hot wind blowing outside. I’m glad you’re not traveling today. It will probably rain and storm again soon.

I have terrible pains — though not yet unwell. I wonder if you're coming to me up Sir Lowry Pass. And whether you’ll be able to look at Danger Point. It was terrible last night. I kept thinking you must somehow appear — but there was not the slightest trace of you, except for the shaving brush still lying in the room next door.

6 p.m.

I've had visitors all day and couldn't write. Now I want to get up and get some fresh air. The heat is unbearable, I can't take it anymore. Everyone here says they've never had such a day in June. I heard the latest news this afternoon. Lady Gladstone is having a baby, and that’s why they’re going back to England so early. Mrs. Emilie Morton apparently heard something about it down in Cradock and Middelburg — and the Pooles were told the same in Cape Town. They wanted to know if you had said anything to me. I told them that you always keep such secrets to yourself — you are far too shy to make such things known.

Darling, I was downstairs, but Mrs. Morton sent me back to bed. I have a fever and can hardly move the little one. Mrs. Poole is sleeping in your room tonight. Her men are out hunting. Mrs. Nell just brought me your shaving brush to bed.

Darling, will you forgive me? I'll write again soon, when I can get up again. Mrs. Morton says she expected nothing less from those warm clothes last month. I hope you're well."

Horsfall's wife, the writer of this letter, did not sign it nor put her address on its reverse.

I had both ChatGPT and HandwritingOCR read and convert this letter into an editable text / DOC file. When I converted thier text files from German into English using both ChatGPT and Google Translate there were considerable comparative differences between the two versions. This was very disappointing. Ultimately I compared both translations and edited them to produce my own version.

* With regard to her husband wanting to "scold / hit" her, these are two very different interpretations taken from translation of ChatGPT's and HandwritingOCR' OCR'ed text. I decided to leave both in so as to allow the reader to choose the word that best describes their opinion of this developing domestic drama in Hermanus all those years ago.