Courts, Drostdys & Magisterial Residencies

Quote from Steve on October 8, 2025, 2:22 pmAs a preface to this post, here is a little introduction to the effect that the rule of law had on some of South Africa's people.

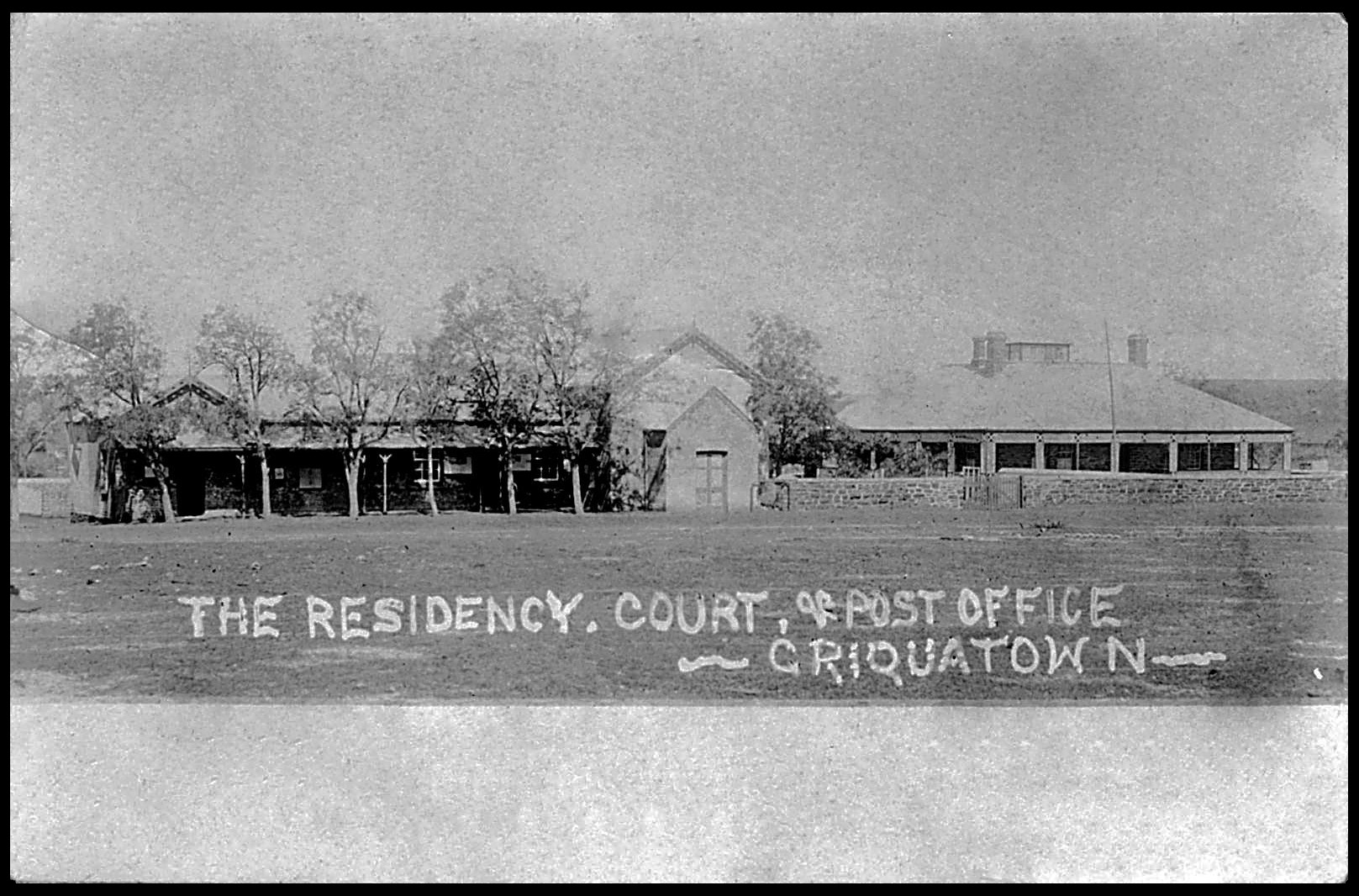

Griquatown Residency, Court and Post Office

I thought to start this thread with this postcard which I bought many years ago from a rather reluctant Paul van Zeyl who had been planning an unrealised Griqualand West display.

1914. 'The Residency, Court House & Post Office - Griquatown'. Unstamped. '17 / 11 / 14'.

The stone building right survives today on Main Street, Griquatown. It was presumably the Residency.

The original is a faded sepia photo. This has been restored by AI (ChatGPT).The history of Griqualand and the Griquas begins in the Cape, the ancestrral home of the Khoi. In 1740 they were a small Khoi clan of pastoralists, a remnant of the Guriqua, in the vicinity of Piquetberg who offered refuge to runaway slaves and Europeans who had problems with Dutch colonial rule and its oppresive, slavery-supporting Roman-Dutch law.

Over time this group increasingly mixed-race people became known as ‘Basters’ or ‘Bastaards sought freedom from Dutch colonial rule. Their solution was to trekked out of the Dutch Cape into the hinterlands under the leadership of ex-slave Adam Kok 1st. Over decades the Basters slowly passed through Namaqualand until settling along the Gariep (Orange River), the northern border of the Dutch colony. Eventually they crossed the river to settle on its far bank outside of colonial jurisdiction, both Dutch and British.

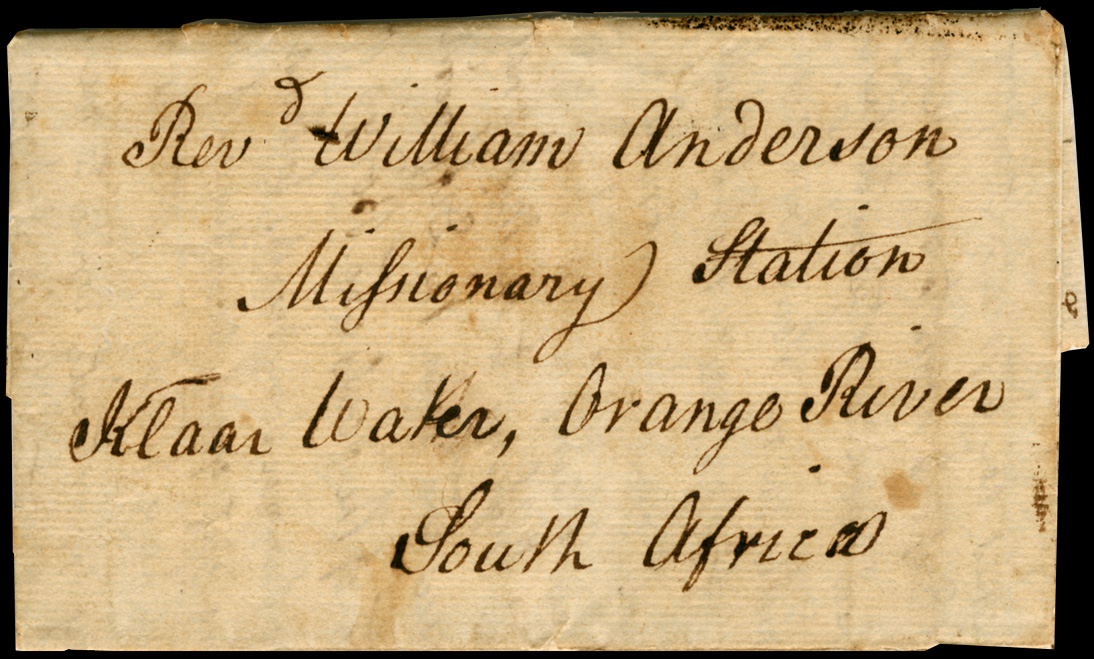

In 1801 the first LMS (London Missionary Society) Station north of the Orange River was founded among the Basters at Klaarwater by the Revds William Anderson and Nicholas Kramer. This settlement was soon so successful that in 1805 the traveller, Dr Heinrich Lichtenstein, described it as a “Hottentot Republic under the patriarchal government of the missionaries”. On his second visit to Klaarwater in 1819 (see cover below) the LMS's inspector of mission stations, the Rev. Dr Campbell, renamed the settlement at Klaarwater 'Griquatown because he objected to his mission station’s mixed-race parishioners being called ‘Bastards’.

1818. Entire letter from SPITALFIELDS, LONDON, 8th Nov 1818’ to KLAARWATER ‘received 1819’.

Addressed to the Revd William Anderson at the LMS Missionary Station, Klaarwater.

This was addressed to Klaarwater before Rev. Dr Campbell changed it to 'Griquatown'.The above letter's contents reveal that the writer had arranged for the Rev. Dr John Campbell to deliver this letter to Rev. Anderson at Klaarwater. It is believed to be one of the first, if not the earliest, letter to be delivered north of the Orange River. (1819.)

The territory of the Griqua clan was controlled by three families - the Koks, Barendses and Waterboers. They were not a united people and after violent disagreements Adam Kok II left to settle around the new London Missionary Station at Phillipolis. Like the Khoi before them the Griquas lacked cohesion and political unity. Largely illiterate they had no written or binding laws to glue their society together. When 'Boer' trekkers into what was to be the south-western Orange Free State after 1836 their arrival would lead to its slow legal dismantling of the Griqua clan claim to the land. This collapse would be accelerated once diamonds were discovered in their disputed territory in 1866/7 and the Boer states and the Cape Colonial power saw the value in it.

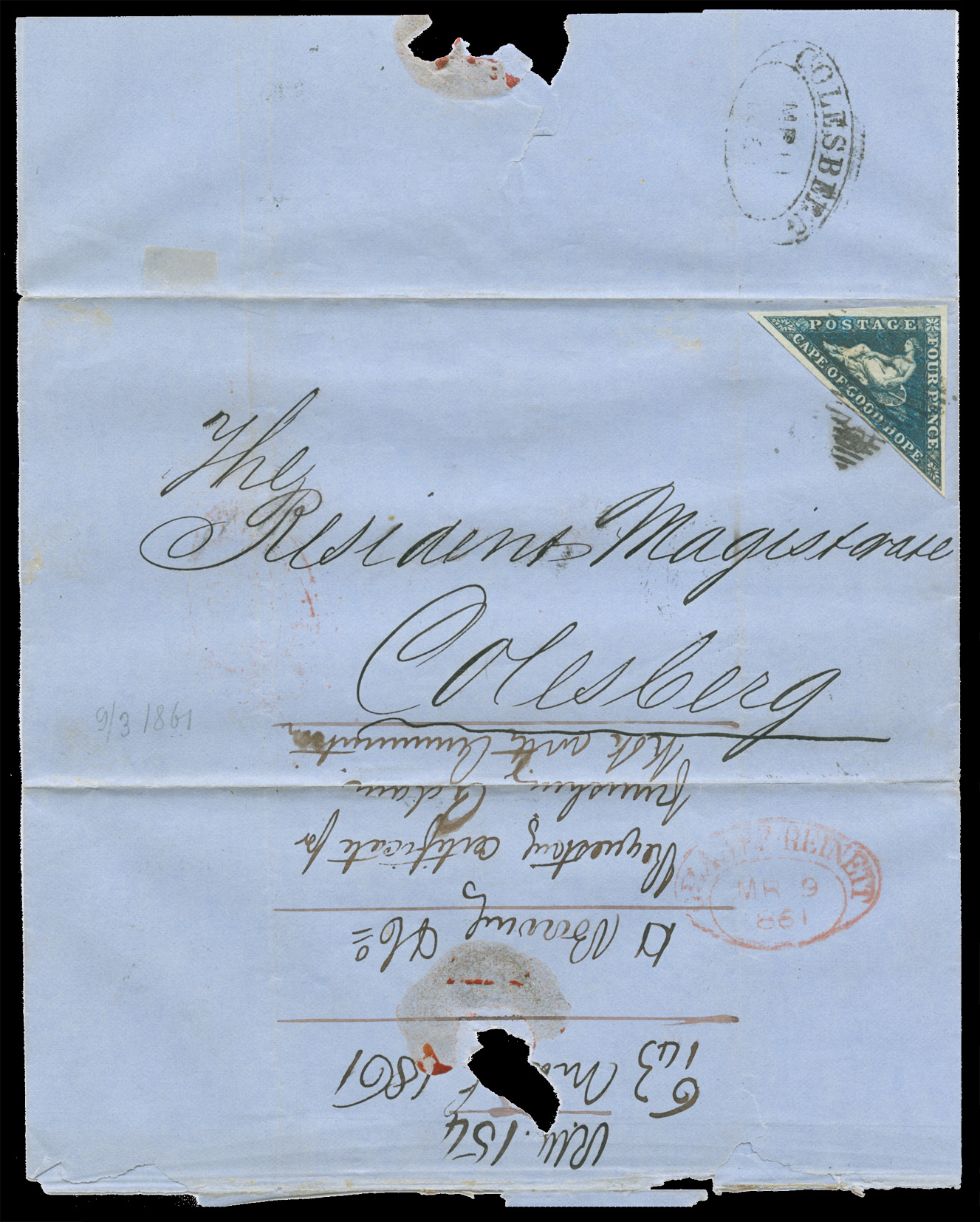

1861. Cover RM (Resident Magistrate) GRAAFF REINET 'MR 9 1861' to RM COLESBERG 'MR 11 1861'.

This letter granted permission for Adam Kok to purcahse ammunition, possibly for the long trek to East Griqualand.As there was no post office operating in Klaarwater / Griquatown in 1818, mail was conveyed privately in and out by helpful visitors or between mission stations by runners and riders. After the Cape government appointed an agent in Griquatown in 1822 it is thought that mail departed Griquatown in the official mail bag. By 1824, letters were being carried out by wagon. It is thought this mail was probably taken to the post office in Beaufort, (later Beaufort West), 480 km away, from where it entered the weekly eastern frontier mail route to Cape Town. In 1828, the nearest post office to Griquatown was Graaff-Reinet, more than 400 km away.

After Colesberg post office opened in 1841, Griquatown was closer to established postal routes, but even this office was some 400 km away. At this time the regular transport of mail from Griquatown to Colesberg was quite unreliable. It would remain this way until a post office was opened in Hopetown, some 100 km from Griquatown in 1855. By 1873 - 1874 there would be eleven post offices in Griqualand West, two which were run by women. The Griquatown Post Office was run by Mrs A Hughes, a widow, and Junction by a Mrs Adendorff.

Once both Boer and Brit saw the vast potential for huge profits in an area that had previously been too dry, dusty and poor to deserve their attention, they came to covet the Griqua's land, each finding reasons why it more rightly belonged to them than the Griqua. How the decision was reached that Griqualand would become British territory rather than part of the Orange Free State (OFS) was once a well-kept secret. The OFS's desired to be shot of the Griqua 'bastards' and any lingering clam they might have against the land purchases made by Boers who bought Griqua land, then deceitfully lodged the deeds in the OFS, not Griqualand, thereby making Griqua land part of OFS territory.

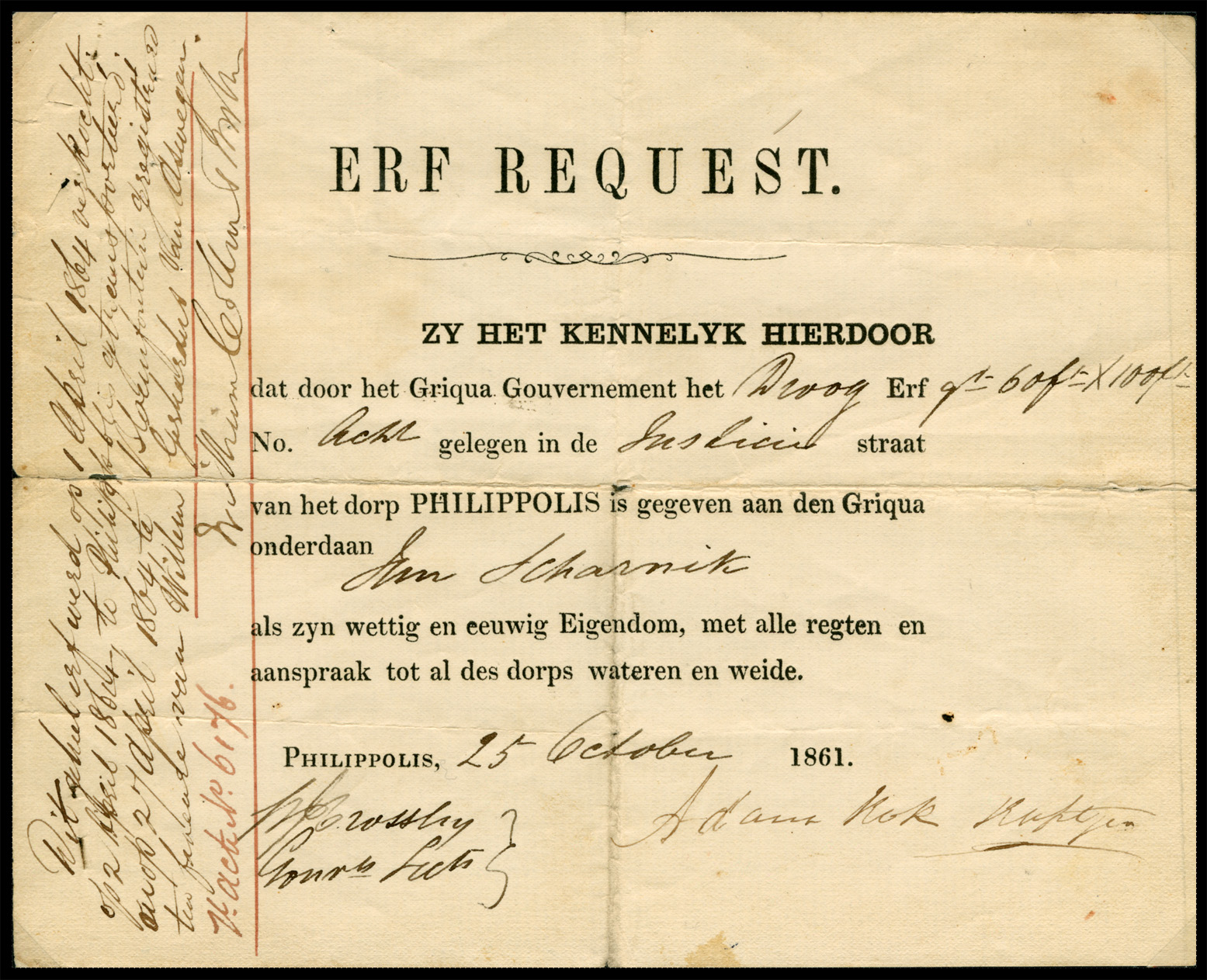

1861. ERF REQUEST '25 October 1861' in PHILIPPOLIS by Adam Kok, Kaptejn.

Land purchases like this plot (erf) were registered in Bloemfontein, not Griqualand.

This was a form of legal trickery intended to make the land part of the OFS.The note on the left reads: "This promissory note was sold on 1 April 1864, signed on 2 April 1864 at Philippolis, and registered on 27 April 1864 at Bloemfontein in favor of Willem Geskardus van Aswegen.

H. Act No. 6176."

(The name if the official is illegible.)The OFS agreed to Britain taking control of the Diamond Fields provided that the Griqua's were cleared out. This the Cape did, relocating many to 'OFS Griqua" to the far side of the Drakensberg in the disputed land of the Xhosa, a place called 'Griqualand East'.

Unaware of the British /OFS intrigue. the Griqua leader Nicholas Waterboer appealed to the British authorities, arguing that his people had long-held rights granted by Britain and that British protection was now necessary to protect their teriritory from the Boers. To resolve the conflict, the matter was put up to 'independent' arbitration under no less an impartial authority of than the British Lieutenant-Governor Robert Keate of Natal. Unsurprisingly, the OFS agreed to his appointment. Complicating matters were the diggers who had flooded in as part of the “diamond rush’ who attempted to set up their own an independent republic.

The Keate Award of 1871 decided in favour of the Griquas who opted for British protection, becoming Griqualand West (GW), a separate Crown Colony in 1873 with its capital at Kimberly. Railways from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London opened the colony up to immigration, capital and industrialisation. From 1873 to 1880, Griquatown was the capital of the Province of Griqualand West. During this time its government offices were likely located in the former mission house built around 1828, today known as the Mary Moffat Museum. There is no record of a specific, dedicated "courthouse" building being constructed in Griquatown.

In 1880 GW was annexed to the Cape Colony. The court house shown top above was presumably built around this time.

A very brief look at some of the Stamps and Postmarks of Griquatown 1886 - 1912. From left:

1877 Cape of Good Hope SG2 1d pale carmine overprinted 'G. W.' in black. Probably used in Cape Town - cancelled BONC 1.

1888 Cape of Good Hope SG21da 4d blue overprinted large 'G' inverted. Fine used, possibly at Orange River.

1885 SG49 Cape of Good Hope 1d red obliterated BONC 529, used GRIQUATOWN 'DE 28 93'.

1886. Province of Griqualand West 5s Bourne Head Revenue cancelled 'NO 8 86' with Squared Circle. Pre-TO so fiscal use.

1912. SG D3 Union of SA Interprovincial use of Transvaal 2d Postage Due cancelled GRIQUATOWN '18 AU 12'.The only stamp among those above likely to have been used in the Griquatown court is the rather wonderful 1886 5/- Bourne head. However, it is more likely an example of telegraphic use rather than fiscal. A TO (Telegraph Office) was opened in Griquatown in 1893, the same year that this stamp was cancelled. Given its high-ish value and the date it has been cancelled on, 28th December 1893, there is a very good chance that this was used in the TO, probably to send a belated Christmas wishes or a New Year message.

As a preface to this post, here is a little introduction to the effect that the rule of law had on some of South Africa's people.

Griquatown Residency, Court and Post Office

I thought to start this thread with this postcard which I bought many years ago from a rather reluctant Paul van Zeyl who had been planning an unrealised Griqualand West display.

1914. 'The Residency, Court House & Post Office - Griquatown'. Unstamped. '17 / 11 / 14'.

The stone building right survives today on Main Street, Griquatown. It was presumably the Residency.

The original is a faded sepia photo. This has been restored by AI (ChatGPT).

The history of Griqualand and the Griquas begins in the Cape, the ancestrral home of the Khoi. In 1740 they were a small Khoi clan of pastoralists, a remnant of the Guriqua, in the vicinity of Piquetberg who offered refuge to runaway slaves and Europeans who had problems with Dutch colonial rule and its oppresive, slavery-supporting Roman-Dutch law.

Over time this group increasingly mixed-race people became known as ‘Basters’ or ‘Bastaards sought freedom from Dutch colonial rule. Their solution was to trekked out of the Dutch Cape into the hinterlands under the leadership of ex-slave Adam Kok 1st. Over decades the Basters slowly passed through Namaqualand until settling along the Gariep (Orange River), the northern border of the Dutch colony. Eventually they crossed the river to settle on its far bank outside of colonial jurisdiction, both Dutch and British.

In 1801 the first LMS (London Missionary Society) Station north of the Orange River was founded among the Basters at Klaarwater by the Revds William Anderson and Nicholas Kramer. This settlement was soon so successful that in 1805 the traveller, Dr Heinrich Lichtenstein, described it as a “Hottentot Republic under the patriarchal government of the missionaries”. On his second visit to Klaarwater in 1819 (see cover below) the LMS's inspector of mission stations, the Rev. Dr Campbell, renamed the settlement at Klaarwater 'Griquatown because he objected to his mission station’s mixed-race parishioners being called ‘Bastards’.

1818. Entire letter from SPITALFIELDS, LONDON, 8th Nov 1818’ to KLAARWATER ‘received 1819’.

Addressed to the Revd William Anderson at the LMS Missionary Station, Klaarwater.

This was addressed to Klaarwater before Rev. Dr Campbell changed it to 'Griquatown'.

The above letter's contents reveal that the writer had arranged for the Rev. Dr John Campbell to deliver this letter to Rev. Anderson at Klaarwater. It is believed to be one of the first, if not the earliest, letter to be delivered north of the Orange River. (1819.)

The territory of the Griqua clan was controlled by three families - the Koks, Barendses and Waterboers. They were not a united people and after violent disagreements Adam Kok II left to settle around the new London Missionary Station at Phillipolis. Like the Khoi before them the Griquas lacked cohesion and political unity. Largely illiterate they had no written or binding laws to glue their society together. When 'Boer' trekkers into what was to be the south-western Orange Free State after 1836 their arrival would lead to its slow legal dismantling of the Griqua clan claim to the land. This collapse would be accelerated once diamonds were discovered in their disputed territory in 1866/7 and the Boer states and the Cape Colonial power saw the value in it.

1861. Cover RM (Resident Magistrate) GRAAFF REINET 'MR 9 1861' to RM COLESBERG 'MR 11 1861'.

This letter granted permission for Adam Kok to purcahse ammunition, possibly for the long trek to East Griqualand.

As there was no post office operating in Klaarwater / Griquatown in 1818, mail was conveyed privately in and out by helpful visitors or between mission stations by runners and riders. After the Cape government appointed an agent in Griquatown in 1822 it is thought that mail departed Griquatown in the official mail bag. By 1824, letters were being carried out by wagon. It is thought this mail was probably taken to the post office in Beaufort, (later Beaufort West), 480 km away, from where it entered the weekly eastern frontier mail route to Cape Town. In 1828, the nearest post office to Griquatown was Graaff-Reinet, more than 400 km away.

After Colesberg post office opened in 1841, Griquatown was closer to established postal routes, but even this office was some 400 km away. At this time the regular transport of mail from Griquatown to Colesberg was quite unreliable. It would remain this way until a post office was opened in Hopetown, some 100 km from Griquatown in 1855. By 1873 - 1874 there would be eleven post offices in Griqualand West, two which were run by women. The Griquatown Post Office was run by Mrs A Hughes, a widow, and Junction by a Mrs Adendorff.

Once both Boer and Brit saw the vast potential for huge profits in an area that had previously been too dry, dusty and poor to deserve their attention, they came to covet the Griqua's land, each finding reasons why it more rightly belonged to them than the Griqua. How the decision was reached that Griqualand would become British territory rather than part of the Orange Free State (OFS) was once a well-kept secret. The OFS's desired to be shot of the Griqua 'bastards' and any lingering clam they might have against the land purchases made by Boers who bought Griqua land, then deceitfully lodged the deeds in the OFS, not Griqualand, thereby making Griqua land part of OFS territory.

1861. ERF REQUEST '25 October 1861' in PHILIPPOLIS by Adam Kok, Kaptejn.

Land purchases like this plot (erf) were registered in Bloemfontein, not Griqualand.

This was a form of legal trickery intended to make the land part of the OFS.

The note on the left reads: "This promissory note was sold on 1 April 1864, signed on 2 April 1864 at Philippolis, and registered on 27 April 1864 at Bloemfontein in favor of Willem Geskardus van Aswegen.

H. Act No. 6176."

(The name if the official is illegible.)

The OFS agreed to Britain taking control of the Diamond Fields provided that the Griqua's were cleared out. This the Cape did, relocating many to 'OFS Griqua" to the far side of the Drakensberg in the disputed land of the Xhosa, a place called 'Griqualand East'.

Unaware of the British /OFS intrigue. the Griqua leader Nicholas Waterboer appealed to the British authorities, arguing that his people had long-held rights granted by Britain and that British protection was now necessary to protect their teriritory from the Boers. To resolve the conflict, the matter was put up to 'independent' arbitration under no less an impartial authority of than the British Lieutenant-Governor Robert Keate of Natal. Unsurprisingly, the OFS agreed to his appointment. Complicating matters were the diggers who had flooded in as part of the “diamond rush’ who attempted to set up their own an independent republic.

The Keate Award of 1871 decided in favour of the Griquas who opted for British protection, becoming Griqualand West (GW), a separate Crown Colony in 1873 with its capital at Kimberly. Railways from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London opened the colony up to immigration, capital and industrialisation. From 1873 to 1880, Griquatown was the capital of the Province of Griqualand West. During this time its government offices were likely located in the former mission house built around 1828, today known as the Mary Moffat Museum. There is no record of a specific, dedicated "courthouse" building being constructed in Griquatown.

In 1880 GW was annexed to the Cape Colony. The court house shown top above was presumably built around this time.

A very brief look at some of the Stamps and Postmarks of Griquatown 1886 - 1912. From left:

1877 Cape of Good Hope SG2 1d pale carmine overprinted 'G. W.' in black. Probably used in Cape Town - cancelled BONC 1.

1888 Cape of Good Hope SG21da 4d blue overprinted large 'G' inverted. Fine used, possibly at Orange River.

1885 SG49 Cape of Good Hope 1d red obliterated BONC 529, used GRIQUATOWN 'DE 28 93'.

1886. Province of Griqualand West 5s Bourne Head Revenue cancelled 'NO 8 86' with Squared Circle. Pre-TO so fiscal use.

1912. SG D3 Union of SA Interprovincial use of Transvaal 2d Postage Due cancelled GRIQUATOWN '18 AU 12'.

The only stamp among those above likely to have been used in the Griquatown court is the rather wonderful 1886 5/- Bourne head. However, it is more likely an example of telegraphic use rather than fiscal. A TO (Telegraph Office) was opened in Griquatown in 1893, the same year that this stamp was cancelled. Given its high-ish value and the date it has been cancelled on, 28th December 1893, there is a very good chance that this was used in the TO, probably to send a belated Christmas wishes or a New Year message.

Quote from Steve on October 14, 2025, 9:54 amCape Courts under the Rule of the VOC: 1652 - 1795.

Here is the start of a more 'scholarly' approach to this subject with a complete chronological list of the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or Dutch East India Company) drostdyen (magisterial districts) at the Cape of Good Hope from 1652–1795, with approximate dates of establishment and key notes.

Ultimately I will attempt to cover the introduction of European law into South Africa under a broader title in four parts, the Development of Magisteries in South Africa, 1652–1890, including the Cape, Natal, the Orange Free State and ZAR. This will be illustrated with postcards, postal history and stamps which pertain to judicial matters.

Our thanks to 'Herrie van der Spiegel' for this instructive page from his 'History of South Africa'.

VOC Drostdyen (Magisteries) at the Cape: 1652 - 1795

These administrative centers of Roman Dutch law developed in the following order, starting with the arrival at the Cape of Commander Jan van Riebeeck. Initially, only the European employees of the VOC at the Cape were subject to its rules and regulations as well as the law of the Netherlands. As the Cape was founded as a replenishment station, not a colony, the indigenous population were not subject to Dutch laws. However, this would change once the first free burgher farmers ('Boers') were created and a colony started by default.

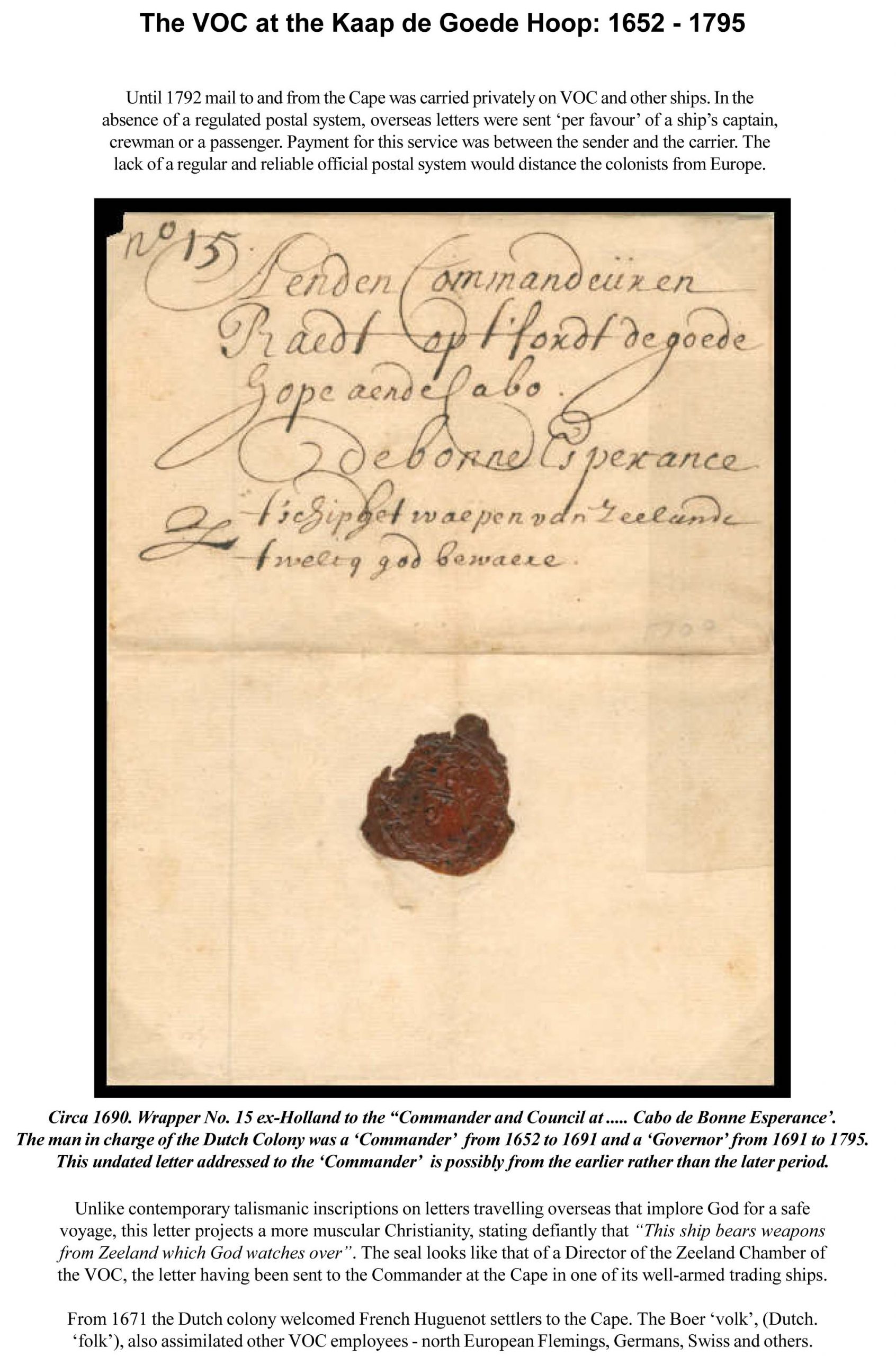

Circa 1958. Union-Castle Shipping Line Menu Card.

This illustration gloriously glosses over the reality of VOC rule at the Cape.

The start of colonisation can be seen in the master-servant relationship, the slaves and the import of plants.1]. Cape District (Kaapstad).

Est. 1652

Cape Town Castle

The original VOC administrative and judicial center. Justice administered by the Raad van Justitie (Council of Justice) and Politieke Raad. Served the entire colony until rural magisteries were created.

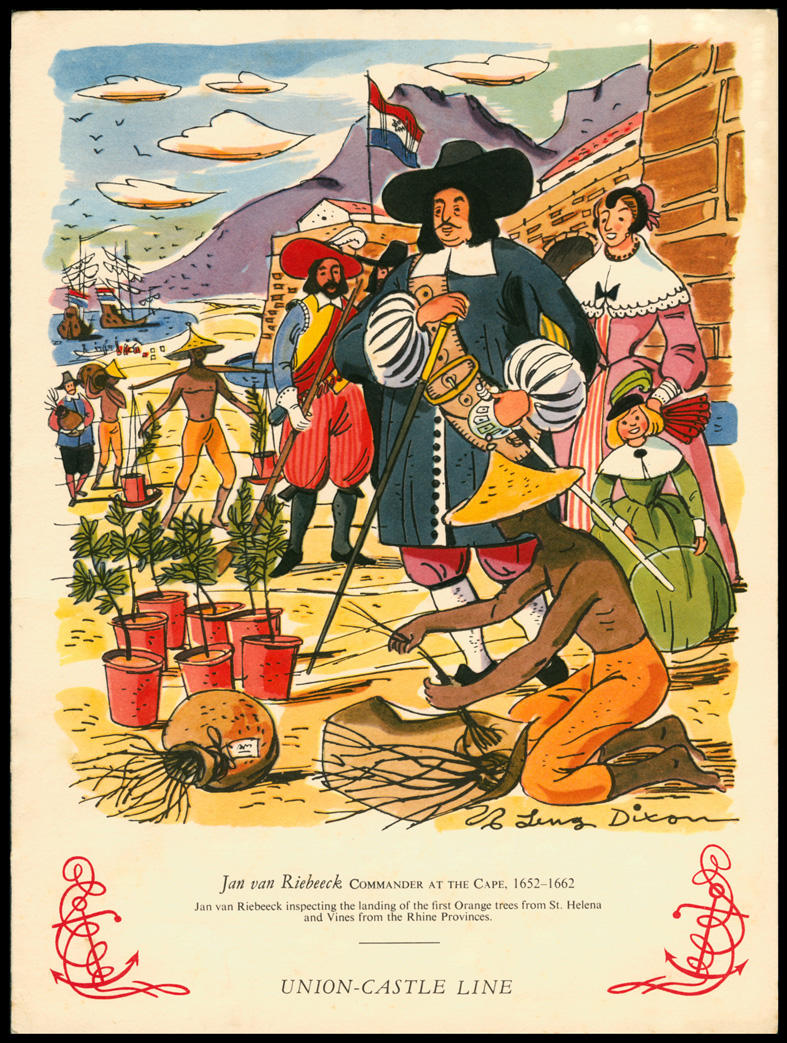

Circa pre 1795 (British Occupation). Cover. Addressed to the 'Raad van Politie' (Political Council).

Perhaps this horribly foxed cover is from an irate burger disllusioned with the VOC's failure?

As there was no domestic Cape Dutch post office, this was probably delivered in person or by slave, servant or favour.

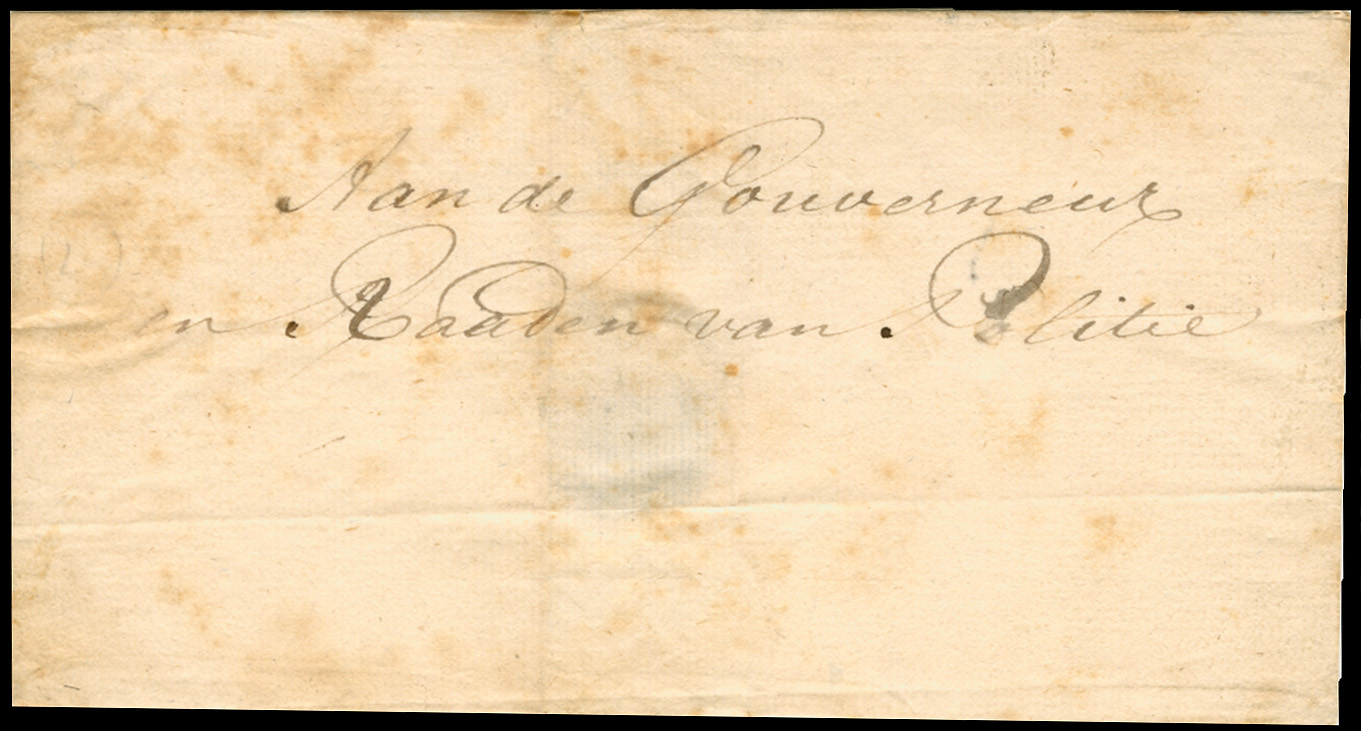

Circa 1985. Postcard. Unused. 'Die Braak with Burgerhuis in the foreground, Stellenbosch'. (NPD.)

'Die Braak' (Afr. fallow land) is a reference to an open space, possibly common land.

This postcard shows the modern heart of the old VOC town with the Kruithuis, (Afr. Arsenal), centre right, built 1680.

The Burgerhuis, foreground, was built in 1797 (first British Occupation period) by a third generation South African.

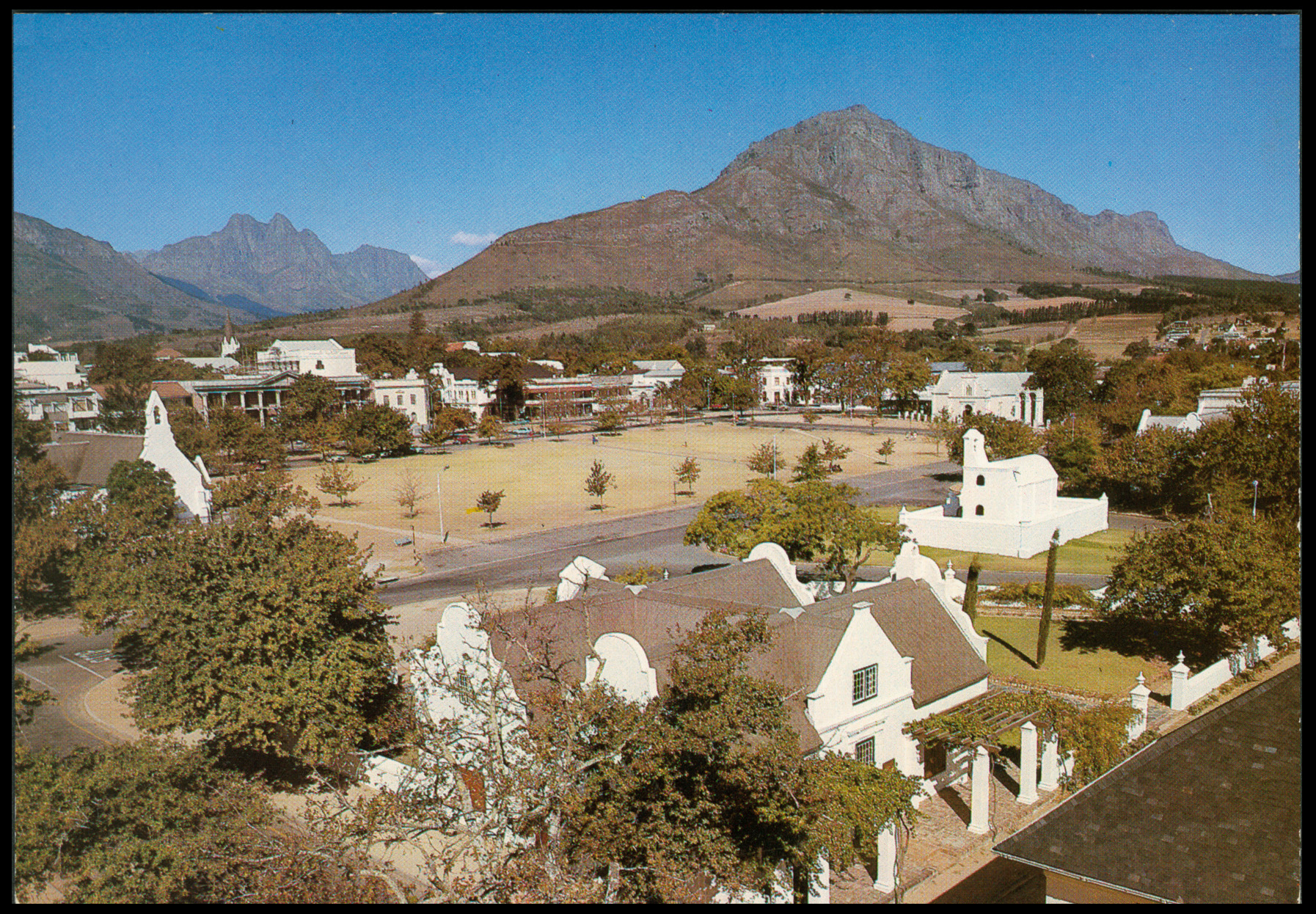

The 'Burgerhuis' was a residential building, not a civil administrative one.2]. District: Stellenbosch

1679 (district founded),

1685 (first Landdrost appointed)

Seat: Stellenbosch

Created by Governor Simon van der Stel to administer the eastern farms and settlements. Heemraden appointed in 1682, making it the first formal drostdy outside of de Kaap , Kaapstad / Cape Town.3]. District: Drakenstein

1691 (district created)

Seat: shared with Stellenbosch

Functioned under the Landdrost and Heemraden of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein. Included present-day Paarl and Franschhoek. Separate drostdy only established later (19th century).4]. Swellendam.

1745 (district founded)

Seat: Swellendam.

Second full drostdy beyond Stellenbosch, established under Governor Hendrik Swellengrebel to serve the Overberg region and frontier farmers. First landdrost: Pieter van der Byl.5]. Tulbagh (Land van Waveren)

1743–1745 (as subdistrict of Stellenbosch)

1790 (formal drostdy)

Seat: Tulbagh

Originated as an outpost of Stellenbosch; elevated to full drostdy shortly before British occupation. Sometimes counted as part of the Stellenbosch/Drakenstein jurisdiction until 1790.6]. Graaff-Reinet

1786 (formal drostdy)

Seat: Graaff-Reinet

Third inland drostdy, created under Governor Cornelis Jacob van de Graaff to control the eastern frontier settlers (the “trekboers”) who had come into conflict with the Xhosa. First landdrost: Pieter van der Merwe.Landdrost:

The chief magistrate and local VOC official, combining judicial, executive, and sometimes military powers.Drostdy:

The office, residence, and jurisdiction of a landdrost, or local administrator. The drostdy served as the center of local government, often containing the landdrost's office, courtroom, and living quarters, along with other outbuildings like a gaol or mill. Historically, a drostdy also referred to the magisterial district itself.Heemraden:

Local burghers appointed to assist the landdrost in minor judicial and administrative matters (like a rural council).Raad van Justitie (Council of Justice):

The supreme court seated at the Castle in Cape Town.The First British Occupation (end of VOC rule): 1795 - 1803

At the time of the first British occupation (September 1795), the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope was divided into four principal drostdyen. These were:

Cape District (the Castle and Cape Peninsula environs)

Stellenbosch & Drakenstein (combined jurisdiction)

Swellendam

Graaff-Reinet(Tulbagh was only just emerging as a separate jurisdiction.)

Our thanks to 'Herrie van der Spiegel' for this instructive page from his 'History of South Africa'.

Cape Courts under the Rule of the VOC: 1652 - 1795.

Here is the start of a more 'scholarly' approach to this subject with a complete chronological list of the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or Dutch East India Company) drostdyen (magisterial districts) at the Cape of Good Hope from 1652–1795, with approximate dates of establishment and key notes.

Ultimately I will attempt to cover the introduction of European law into South Africa under a broader title in four parts, the Development of Magisteries in South Africa, 1652–1890, including the Cape, Natal, the Orange Free State and ZAR. This will be illustrated with postcards, postal history and stamps which pertain to judicial matters.

Our thanks to 'Herrie van der Spiegel' for this instructive page from his 'History of South Africa'.

VOC Drostdyen (Magisteries) at the Cape: 1652 - 1795

These administrative centers of Roman Dutch law developed in the following order, starting with the arrival at the Cape of Commander Jan van Riebeeck. Initially, only the European employees of the VOC at the Cape were subject to its rules and regulations as well as the law of the Netherlands. As the Cape was founded as a replenishment station, not a colony, the indigenous population were not subject to Dutch laws. However, this would change once the first free burgher farmers ('Boers') were created and a colony started by default.

Circa 1958. Union-Castle Shipping Line Menu Card.

This illustration gloriously glosses over the reality of VOC rule at the Cape.

The start of colonisation can be seen in the master-servant relationship, the slaves and the import of plants.

1]. Cape District (Kaapstad).

Est. 1652

Cape Town Castle

The original VOC administrative and judicial center. Justice administered by the Raad van Justitie (Council of Justice) and Politieke Raad. Served the entire colony until rural magisteries were created.

Circa pre 1795 (British Occupation). Cover. Addressed to the 'Raad van Politie' (Political Council).

Perhaps this horribly foxed cover is from an irate burger disllusioned with the VOC's failure?

As there was no domestic Cape Dutch post office, this was probably delivered in person or by slave, servant or favour.

Circa 1985. Postcard. Unused. 'Die Braak with Burgerhuis in the foreground, Stellenbosch'. (NPD.)

'Die Braak' (Afr. fallow land) is a reference to an open space, possibly common land.

This postcard shows the modern heart of the old VOC town with the Kruithuis, (Afr. Arsenal), centre right, built 1680.

The Burgerhuis, foreground, was built in 1797 (first British Occupation period) by a third generation South African.

The 'Burgerhuis' was a residential building, not a civil administrative one.

2]. District: Stellenbosch

1679 (district founded),

1685 (first Landdrost appointed)

Seat: Stellenbosch

Created by Governor Simon van der Stel to administer the eastern farms and settlements. Heemraden appointed in 1682, making it the first formal drostdy outside of de Kaap , Kaapstad / Cape Town.

3]. District: Drakenstein

1691 (district created)

Seat: shared with Stellenbosch

Functioned under the Landdrost and Heemraden of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein. Included present-day Paarl and Franschhoek. Separate drostdy only established later (19th century).

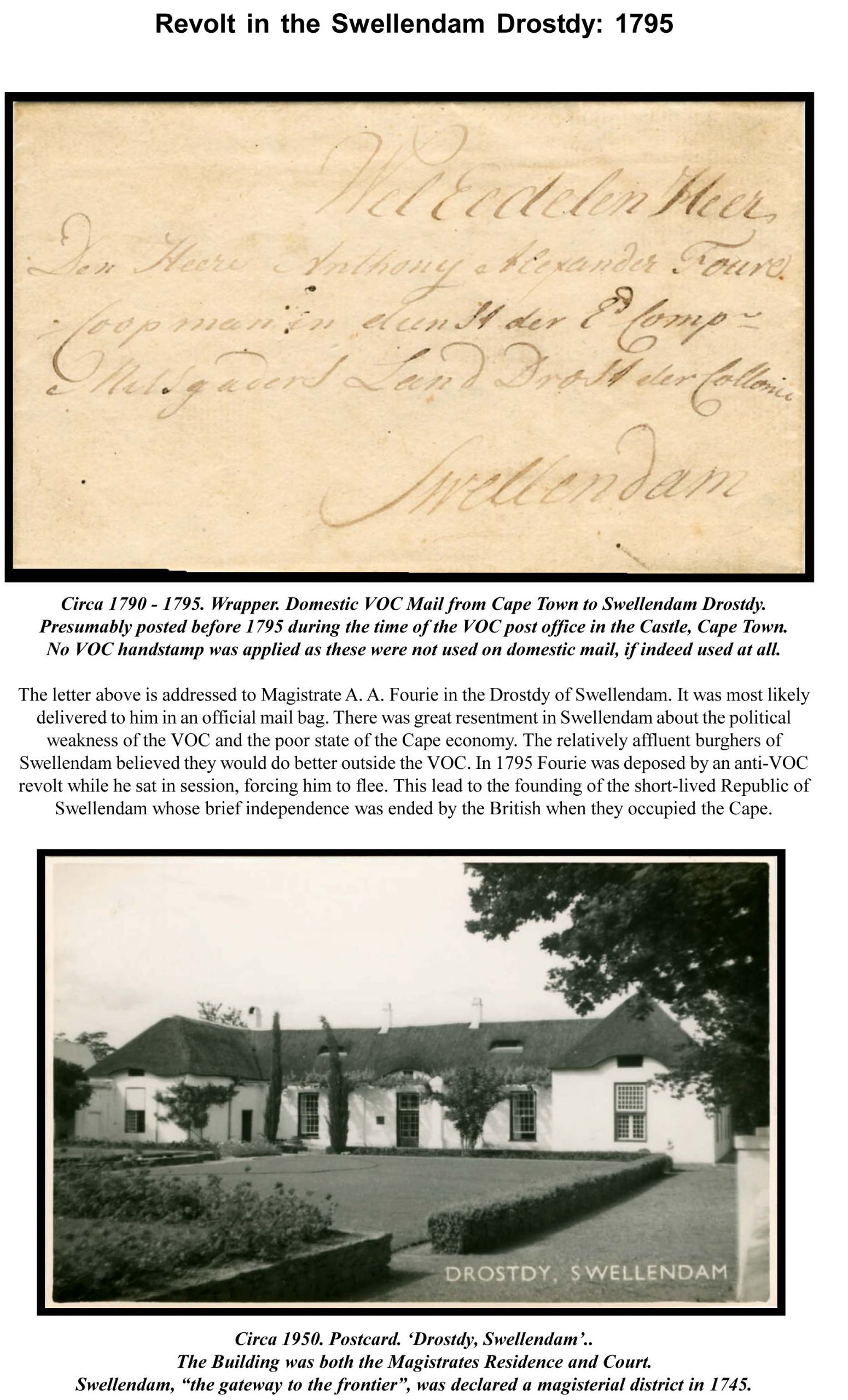

4]. Swellendam.

1745 (district founded)

Seat: Swellendam.

Second full drostdy beyond Stellenbosch, established under Governor Hendrik Swellengrebel to serve the Overberg region and frontier farmers. First landdrost: Pieter van der Byl.

5]. Tulbagh (Land van Waveren)

1743–1745 (as subdistrict of Stellenbosch)

1790 (formal drostdy)

Seat: Tulbagh

Originated as an outpost of Stellenbosch; elevated to full drostdy shortly before British occupation. Sometimes counted as part of the Stellenbosch/Drakenstein jurisdiction until 1790.

6]. Graaff-Reinet

1786 (formal drostdy)

Seat: Graaff-Reinet

Third inland drostdy, created under Governor Cornelis Jacob van de Graaff to control the eastern frontier settlers (the “trekboers”) who had come into conflict with the Xhosa. First landdrost: Pieter van der Merwe.

Landdrost:

The chief magistrate and local VOC official, combining judicial, executive, and sometimes military powers.

Drostdy:

The office, residence, and jurisdiction of a landdrost, or local administrator. The drostdy served as the center of local government, often containing the landdrost's office, courtroom, and living quarters, along with other outbuildings like a gaol or mill. Historically, a drostdy also referred to the magisterial district itself.

Heemraden:

Local burghers appointed to assist the landdrost in minor judicial and administrative matters (like a rural council).

Raad van Justitie (Council of Justice):

The supreme court seated at the Castle in Cape Town.

The First British Occupation (end of VOC rule): 1795 - 1803

At the time of the first British occupation (September 1795), the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope was divided into four principal drostdyen. These were:

Cape District (the Castle and Cape Peninsula environs)

Stellenbosch & Drakenstein (combined jurisdiction)

Swellendam

Graaff-Reinet

(Tulbagh was only just emerging as a separate jurisdiction.)

Our thanks to 'Herrie van der Spiegel' for this instructive page from his 'History of South Africa'.

Quote from Steve on October 23, 2025, 6:11 pmCape of Good Hope: From VOC to British and Batavian Administration (1786–1806)

The Cape came under British occupation between 1795–1803, The VOC was liquidated in 1800. Throughout this period the Cape's British military maintained its administration from the Castle, Cape Town while retaining Dutch administrative structures, including drostdies and Landdrosts, The four existing drostdys established by the VOC remained in place throughout the period of the first British occupation of the Cape. These were -

Cape District (seat: Cape Town),

Stellenbosch & Drakenstein (seat: Stellenbosch),

Swellendam (seat: Swellendam) and

Graaff-Reinet (seat: Graaff-Reinet)After the Treaty of Amiens Britain returned the Cape to the Batavian Republic in 1803. During the period 1803–1806 the Batavian Commissioner-General of the Cape Colony, Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist, added two new districts to his administration in 1804. His aim was to ease administration by dividing the colony's drostdys or magisterial districts into six of smaller size areas. In doing so, he created two new districts, Tulbagh / Roodezand (seat: Tulbagh) and Uitenhage (seat: Uitenhage).

Cape of Good Hope during the Second Occupation (1806 - 1814) and ownership to 1910.

Early British Occupation 1806 - 1827

Great Britain acquired the Cape Colony by the London Convention of August 13, 1814, part of the general settlement of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. The Congress of Vienna of 1815 took cognizance of that convention. A complicated financial arrangement expedited the transfer of the Cape of Good Hope from the Netherlands to Britain. The Prince of Orange, later King William I of the Netherlands, accepted British payment of £6m for the Cape. However, only £2m went to the Dutch government to be used to fortify the southern frontier of the enlarged Dutch state against France. Three million pounds was paid to settle a Dutch debt with Russia and one million pounds went to Sweden to settle another obligation. This £6m payment made Britain the bona fide, paid-up owner of the once Dutch Cape Colony.

The British began by working within Dutch administrative structures, including drostdies and Landdrosts, while gradually introducing reforms. The continuity was pragmatic, though changes in legal administration were underway. (Under Dutch rule the Landdrost was the chief magistrate/administrator of a drostdy. The term “drostdy” originally referred both to the district over which the Landdrost had jurisdiction and to his official residence or court.) Under the Earl of Caledon, (Governor of the Cape 1807-1811), the first circuit courts for the country districts were proclaimed (16 May 1811). The aim was largely to bring superior justice to out-of-district areas. This signalled the British desire to reform the legal/administrative systemn it had inherited. Several earlier drostdies (e.g., Stellenbosch, Swellendam, Graaff-Reinet, Uitenhage) had becomer "independent districts” in the period but were then subject to change after 1827

Major Reforms 1827 - 1828

In Augsut 1827 the old Dutch offices of Landdrost and heemraden were abolished by Ordnance No. 33 and replaced by British-style Civil Commissioners (in charge of “civil divisions”) and Resident Magistrates. This marked a shift to English language administration and British legal/administrative norms. The replacement of the Landdrost/heemraden system by Civil Commissioners / Resident Magistrates was motivated by the British desire to have a unified English-speaking legal system and to remove local Dutch/Heemraad structures. English now became the lanuguage of government, the courts and education. This caused great discontent anong the Cape Dutch and was a motivating factor in the Great Trek of 1835 and the subsequent development of Afrikaner Nationalism. While the reform of 1827/28 is a clear watershed, the actual implementation across all districts took time and local variations occurred.

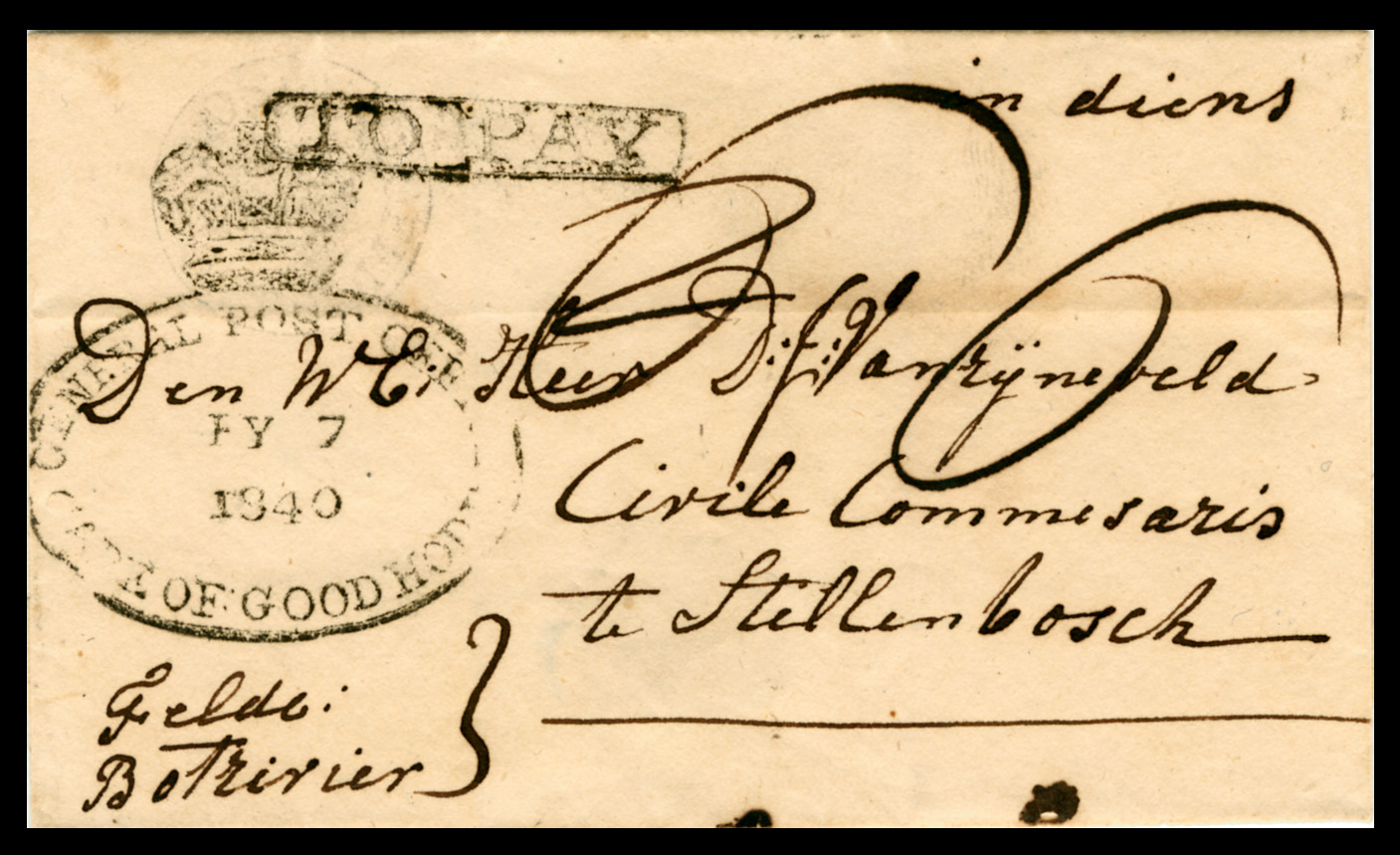

1840. Cover. BOTRIVIER via CAPE TOWN 'FY 7 1840' to "Civil Commissioner" STELLENBOSCH.

(This route does not make sense. Botrivier is much closer to Stellenbosch than Cape Town.)

Marked 'in diens" (Dutch. in service). This was rejected and stamped 'TO PAY''

It is marked 'Felde' as in Field or Veld today, perhaps a reference to troops or a militia.

This cover may suggest the growing antagonism of the Cape Dutch to 'English-only' rule.After 1828 into the later 19th century

On “the first day of 1828, landdrosts and heemraden under the Dutch legal system were replaced by civil commissioners and resident magistrates.” The positions and office had been abolished on 31 Dec 1827. The development of district structures after 1828 included the creation of new districts (such as Albany, Uitenhage etc) and changing boundaries, under the new system of resident magistracy. The term 'drostdy' continued to be used in a reduced sense (often meaning just the residence of the magistrate or the district seat) while the real administrative unit was under the Resident Magistrate and Civil Commissioner. The restructuring aligned the Cape with British colonial administrative norms of district magistracy rather than Dutch-style mixed local councils. The role of Civil Commissioner and Resident Magistrate often overlapped: many were “in charge of civil divisions” as well as acting as magistrate.Up to 1910 (Union of South Africa)

The system of Resident Magistrates and Civil Commissioners persisted, integrated into the colonial (later provincial) governance structure until the Union in 1910. By the end of this period the drostdy/landdrost system had been largely superseded. If it remained at all it was largely historical rather than operational by then.

Cape of Good Hope: From VOC to British and Batavian Administration (1786–1806)

The Cape came under British occupation between 1795–1803, The VOC was liquidated in 1800. Throughout this period the Cape's British military maintained its administration from the Castle, Cape Town while retaining Dutch administrative structures, including drostdies and Landdrosts, The four existing drostdys established by the VOC remained in place throughout the period of the first British occupation of the Cape. These were -

Cape District (seat: Cape Town),

Stellenbosch & Drakenstein (seat: Stellenbosch),

Swellendam (seat: Swellendam) and

Graaff-Reinet (seat: Graaff-Reinet)

After the Treaty of Amiens Britain returned the Cape to the Batavian Republic in 1803. During the period 1803–1806 the Batavian Commissioner-General of the Cape Colony, Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist, added two new districts to his administration in 1804. His aim was to ease administration by dividing the colony's drostdys or magisterial districts into six of smaller size areas. In doing so, he created two new districts, Tulbagh / Roodezand (seat: Tulbagh) and Uitenhage (seat: Uitenhage).

Cape of Good Hope during the Second Occupation (1806 - 1814) and ownership to 1910.

Early British Occupation 1806 - 1827

Great Britain acquired the Cape Colony by the London Convention of August 13, 1814, part of the general settlement of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. The Congress of Vienna of 1815 took cognizance of that convention. A complicated financial arrangement expedited the transfer of the Cape of Good Hope from the Netherlands to Britain. The Prince of Orange, later King William I of the Netherlands, accepted British payment of £6m for the Cape. However, only £2m went to the Dutch government to be used to fortify the southern frontier of the enlarged Dutch state against France. Three million pounds was paid to settle a Dutch debt with Russia and one million pounds went to Sweden to settle another obligation. This £6m payment made Britain the bona fide, paid-up owner of the once Dutch Cape Colony.

The British began by working within Dutch administrative structures, including drostdies and Landdrosts, while gradually introducing reforms. The continuity was pragmatic, though changes in legal administration were underway. (Under Dutch rule the Landdrost was the chief magistrate/administrator of a drostdy. The term “drostdy” originally referred both to the district over which the Landdrost had jurisdiction and to his official residence or court.) Under the Earl of Caledon, (Governor of the Cape 1807-1811), the first circuit courts for the country districts were proclaimed (16 May 1811). The aim was largely to bring superior justice to out-of-district areas. This signalled the British desire to reform the legal/administrative systemn it had inherited. Several earlier drostdies (e.g., Stellenbosch, Swellendam, Graaff-Reinet, Uitenhage) had becomer "independent districts” in the period but were then subject to change after 1827

Major Reforms 1827 - 1828

In Augsut 1827 the old Dutch offices of Landdrost and heemraden were abolished by Ordnance No. 33 and replaced by British-style Civil Commissioners (in charge of “civil divisions”) and Resident Magistrates. This marked a shift to English language administration and British legal/administrative norms. The replacement of the Landdrost/heemraden system by Civil Commissioners / Resident Magistrates was motivated by the British desire to have a unified English-speaking legal system and to remove local Dutch/Heemraad structures. English now became the lanuguage of government, the courts and education. This caused great discontent anong the Cape Dutch and was a motivating factor in the Great Trek of 1835 and the subsequent development of Afrikaner Nationalism. While the reform of 1827/28 is a clear watershed, the actual implementation across all districts took time and local variations occurred.

1840. Cover. BOTRIVIER via CAPE TOWN 'FY 7 1840' to "Civil Commissioner" STELLENBOSCH.

(This route does not make sense. Botrivier is much closer to Stellenbosch than Cape Town.)

Marked 'in diens" (Dutch. in service). This was rejected and stamped 'TO PAY''

It is marked 'Felde' as in Field or Veld today, perhaps a reference to troops or a militia.

This cover may suggest the growing antagonism of the Cape Dutch to 'English-only' rule.

After 1828 into the later 19th century

On “the first day of 1828, landdrosts and heemraden under the Dutch legal system were replaced by civil commissioners and resident magistrates.” The positions and office had been abolished on 31 Dec 1827. The development of district structures after 1828 included the creation of new districts (such as Albany, Uitenhage etc) and changing boundaries, under the new system of resident magistracy. The term 'drostdy' continued to be used in a reduced sense (often meaning just the residence of the magistrate or the district seat) while the real administrative unit was under the Resident Magistrate and Civil Commissioner. The restructuring aligned the Cape with British colonial administrative norms of district magistracy rather than Dutch-style mixed local councils. The role of Civil Commissioner and Resident Magistrate often overlapped: many were “in charge of civil divisions” as well as acting as magistrate.

Up to 1910 (Union of South Africa)

The system of Resident Magistrates and Civil Commissioners persisted, integrated into the colonial (later provincial) governance structure until the Union in 1910. By the end of this period the drostdy/landdrost system had been largely superseded. If it remained at all it was largely historical rather than operational by then.

Quote from Steve on October 24, 2025, 1:07 pmHarry Rivers Esq - Landdrost of the Districts of Albany 1821 - 1825 and Swellendam 1826 - 1842

Harry Rivers, (born London, 13th July 1785 – died Cape Town, 6th December 1861), was an English colonial Cape magistrate and Colonial Treasurer General. His tenure as Landdrost of Albany (seat Grahamstown) began in 1821. This was a difficult time for the 1820 Settlers who arrived amid drought and instability on the eastern Cape frontier. Rivers' job combined civil administration, poor relief, and frontier management in a district squeezed between Settler expectations and the politics of keeping peace with the Xhosa beyond the Fish River. Institutionally, Rivers maintained the hybrid Cape system of a Landdrost with heemraden and local courts in Albany.

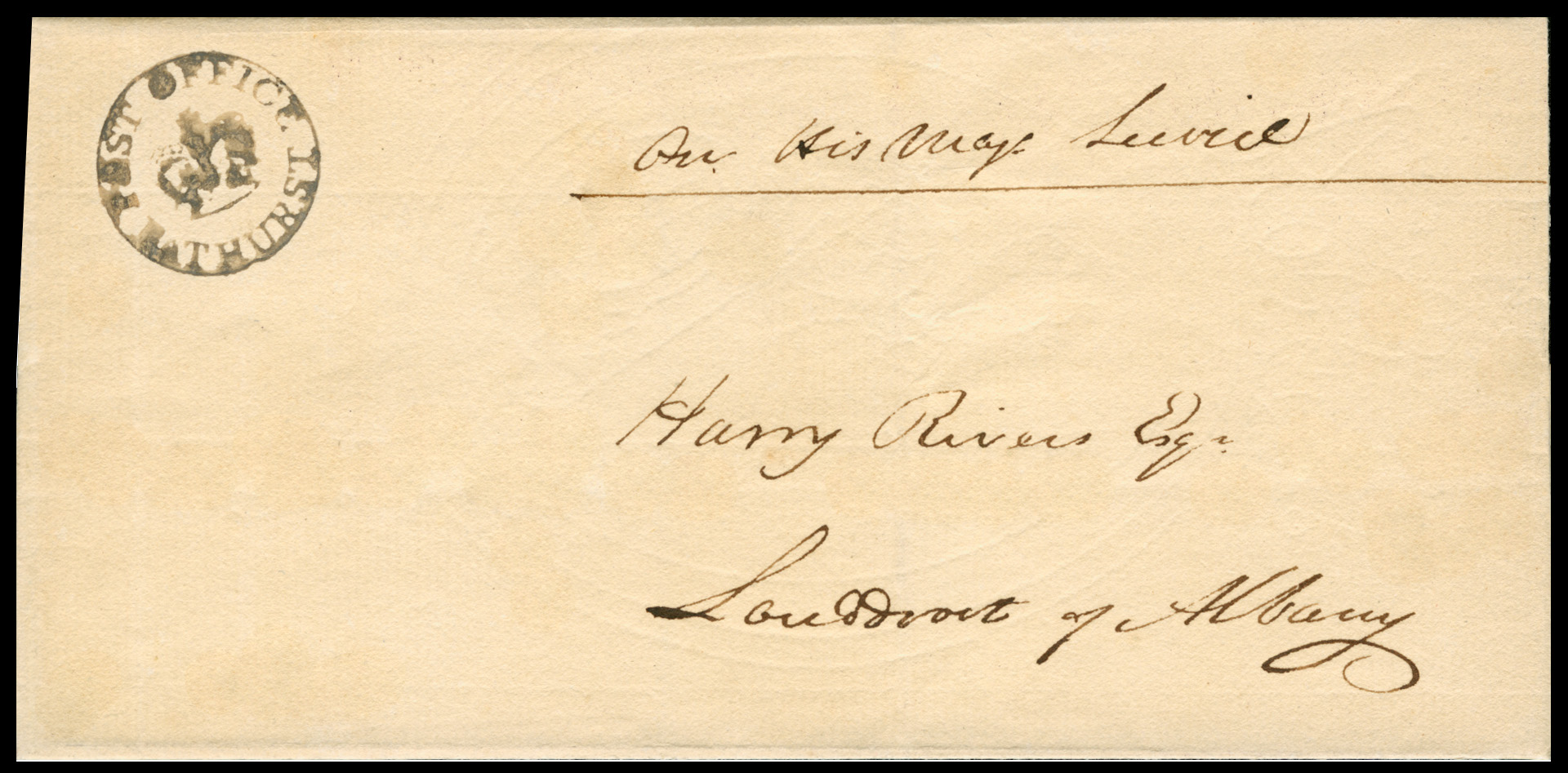

Circa 1823. Cover. BATHURST to GRAHAMSTOWN.

Robert Goldblatt, (Postmarks of the CoGH) states the Bathurst CiC (Crown in Circle) handstamp was issued in 1822.

This cover is therefore dated within the later part of Rivers' tenure as Landdrost of Albany 1821 - 1825.

Given the postmark's relative clarity and sharpness, it is earlier rather than later.

Bathurst was named after the Colonial Secretary, the Earl of Bathurst, Harry Rivers' bete noir!Contemporary sources show that Rivers' relations with parts of the 1820 Settler community were prickly from the outset. Apparently, class distinctions separated him from the Settlers who found him indifferent to their impoverishment by drought and crop failures. It was felt, especially in missionary circles, that Rivers neglected the interests of Settlers. Competent and conscientious to some, aloof and ineffectual to others, he was nevertheless recognised as a hard-working administrator who would later neglect no opportunity to make himself acquainted with the needs of the rural population. In manner, he was typically a conservative English squire of the period.

In 1824 a public controversy erupted in Cape Town alleging Rivers’ indifference to 1820 Settler distress. The Governor ordered an Inquiry, and Rivers countered with a cache of letters from field-cornets, clergy, and settlers affirming his attentiveness - evidence that both the charge and his reputation were hotly contested on political as well as humanitarian grounds. Though the Cape Governor Lord Charles Somerst accepted Rivers' explanations, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in London, the Earl of Bathurst, did not and in 1825 Rivers was relieved of his post. Captain William Bolden Dundas was installed as Landdrost of Albany as his replacement.

Harry Rivers was a son of Francis Rivers of Bradmore, then a rural area of Hammersmith, London. After leaving school he was employed as a clerk in East India House, London. In 1816 his brother-in-law, Henry Alexander, Colonial Secretary to the Cape government, persuaded him to join him and seek his fortune in the Cape Colony. He owed his appointment as Acting Wharfmaster for Table Bay to Alexander’s patronage. However, his brother-in-law died in May 1818 leasving his wife Dorothy, Harrys sister, penniless. This was due to his brother-in-law's various grandiose Cape farming schemes that had lost him his fortune, not made one. In 1818, after appealing to the imperial authorities for relief for herself and her seven children, Dorothy was awarded a pension of £300 pa.

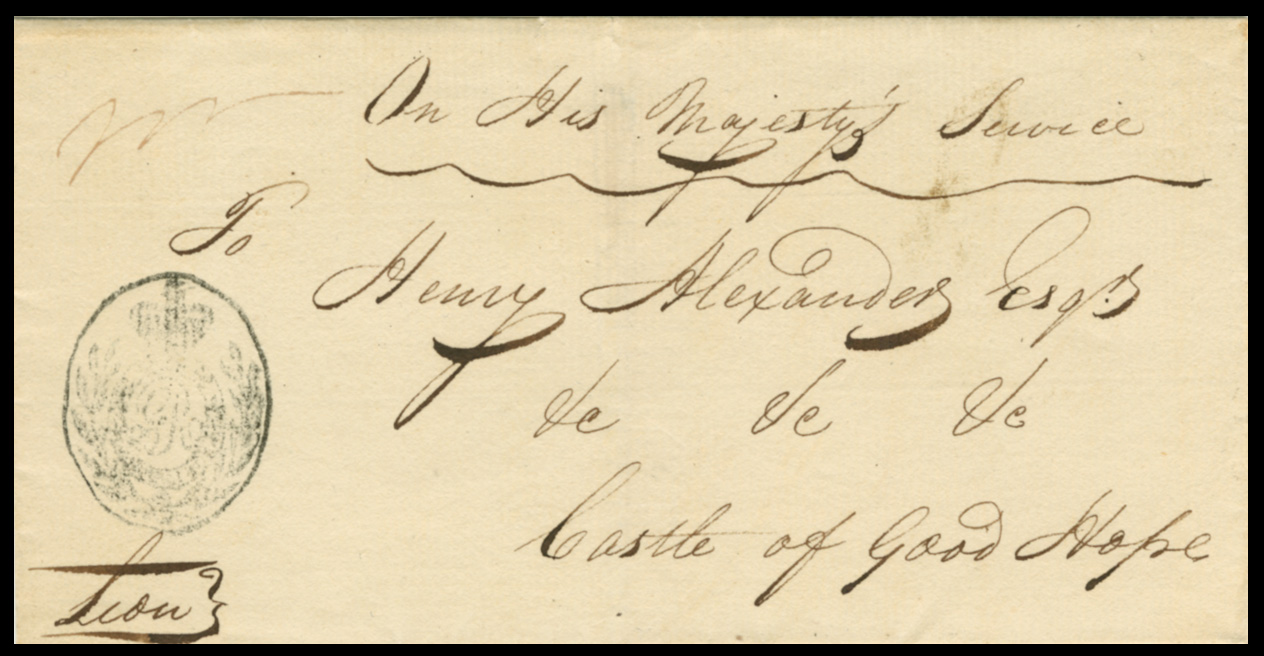

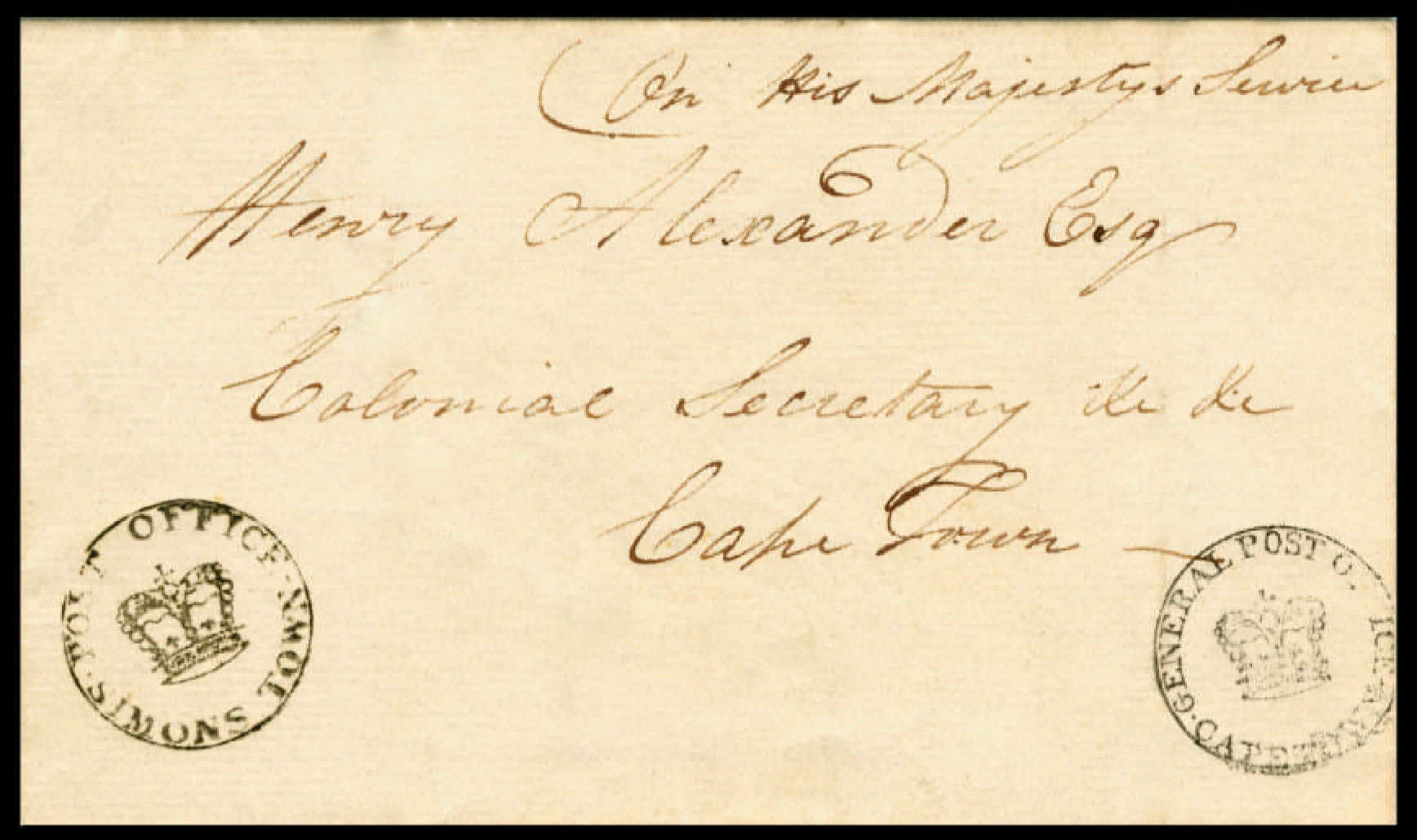

Pre-May 1818. OHMS Cover to Colonial Secretary Henry Alexander at the Castle Cape Town.

Henry Alexander was Harry Rivers' brother-in-law and patron. He would die in 1818.

At this time the Castle was the seat of colonial administrative power.Just over two months after the death of his brother-in-law the Honorable Harry Rivers married Charlotte Johanna Cloete on 27th July 1818. This marriage gave Harry entry into Cape Dutch high society. Charlotte (1788 - 1869) was the eldest child of Pieter Lourens Cloete and the sister of the distinguished Major General Sir Abraham Josias Cloete KCB, a long-serving senior Cape Dutch officer in the British Army. There were three sons from Harry and Charlotte's marriage: Josiah Charles Rivers (1819) afterwards Chief Magistrate of Cape Town and later of Wynberg, Francis Peter Rivers (1820), and Major General Harry Rivers (1821).

Circa 1818. Undated cover from SIMONSTOWN to CAPE TOWN addressed to Colonial Secretary Henery Alexander.

This is a very early CiC (Crown in Circle) cover from Simonstown. It was posted before Alexander died in May 1818.

The first CiC handstamps were issued to Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Simons Town and Uitenhage in 1817.Following Albany, Rivers was transferred to Swellendam at the beginning of 1825 but his appointment was not confirmed for almost two years, most likely as a result of Bathurst’s displeasure. However, at Somerset’s insistence Rivers was eventually reinstated in the service on 14th November 1826. In Swellendam he proved popular with all classes, his administration as both landdrost, starting 1826, and after 1834, as Resident Magistrate and Civil Commissioner being one that was indulgent to the needs of the local people. His interest in the daily life of the farming community was considerable and his wife’s hospitality at the Drostdy was much appreciated.

Rivers improved roads and promoted education and the general welfare of his district. In 1837, Dr William Robertson and others in Swellendam decided to establish a mission station independent of the church and bought the farm Doornkraal for that purpose. Rivers promised his help ‘in every way’ and apparently gave it generously. On 20th August 1838 he was asked to allow the site to be named after him. He agreed but preferred Riversdale to the suggested Riversville, so as to please both English and Dutch communities

On 21 June 1842 he was appointed Treasurer of the Cape Colony. He was given the additional appointment of Paymaster-General in 1851. By now he was widely trusted as an administrator but was overshadowed on the Executive Council. He helped with the drafting of the Constitution of 1853. Under the parliamentary Constitution introduced in 1854, the Treasurer-General was an ex officio member entitled to sit in both Houses but not to vote. He had previously been a member of the nominated Legislative Council, being on good terms with the ‘Easterners’ after having approved that the seat of Easten Cape government be Grahamstown. In 1854 Rivers became chairman of the Prisons Commission. He died in Cape Town in 1861, his wife in 1869.

Harry Rivers Esq - Landdrost of the Districts of Albany 1821 - 1825 and Swellendam 1826 - 1842

Harry Rivers, (born London, 13th July 1785 – died Cape Town, 6th December 1861), was an English colonial Cape magistrate and Colonial Treasurer General. His tenure as Landdrost of Albany (seat Grahamstown) began in 1821. This was a difficult time for the 1820 Settlers who arrived amid drought and instability on the eastern Cape frontier. Rivers' job combined civil administration, poor relief, and frontier management in a district squeezed between Settler expectations and the politics of keeping peace with the Xhosa beyond the Fish River. Institutionally, Rivers maintained the hybrid Cape system of a Landdrost with heemraden and local courts in Albany.

Circa 1823. Cover. BATHURST to GRAHAMSTOWN.

Robert Goldblatt, (Postmarks of the CoGH) states the Bathurst CiC (Crown in Circle) handstamp was issued in 1822.

This cover is therefore dated within the later part of Rivers' tenure as Landdrost of Albany 1821 - 1825.

Given the postmark's relative clarity and sharpness, it is earlier rather than later.

Bathurst was named after the Colonial Secretary, the Earl of Bathurst, Harry Rivers' bete noir!

Contemporary sources show that Rivers' relations with parts of the 1820 Settler community were prickly from the outset. Apparently, class distinctions separated him from the Settlers who found him indifferent to their impoverishment by drought and crop failures. It was felt, especially in missionary circles, that Rivers neglected the interests of Settlers. Competent and conscientious to some, aloof and ineffectual to others, he was nevertheless recognised as a hard-working administrator who would later neglect no opportunity to make himself acquainted with the needs of the rural population. In manner, he was typically a conservative English squire of the period.

In 1824 a public controversy erupted in Cape Town alleging Rivers’ indifference to 1820 Settler distress. The Governor ordered an Inquiry, and Rivers countered with a cache of letters from field-cornets, clergy, and settlers affirming his attentiveness - evidence that both the charge and his reputation were hotly contested on political as well as humanitarian grounds. Though the Cape Governor Lord Charles Somerst accepted Rivers' explanations, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in London, the Earl of Bathurst, did not and in 1825 Rivers was relieved of his post. Captain William Bolden Dundas was installed as Landdrost of Albany as his replacement.

Harry Rivers was a son of Francis Rivers of Bradmore, then a rural area of Hammersmith, London. After leaving school he was employed as a clerk in East India House, London. In 1816 his brother-in-law, Henry Alexander, Colonial Secretary to the Cape government, persuaded him to join him and seek his fortune in the Cape Colony. He owed his appointment as Acting Wharfmaster for Table Bay to Alexander’s patronage. However, his brother-in-law died in May 1818 leasving his wife Dorothy, Harrys sister, penniless. This was due to his brother-in-law's various grandiose Cape farming schemes that had lost him his fortune, not made one. In 1818, after appealing to the imperial authorities for relief for herself and her seven children, Dorothy was awarded a pension of £300 pa.

Pre-May 1818. OHMS Cover to Colonial Secretary Henry Alexander at the Castle Cape Town.

Henry Alexander was Harry Rivers' brother-in-law and patron. He would die in 1818.

At this time the Castle was the seat of colonial administrative power.

Just over two months after the death of his brother-in-law the Honorable Harry Rivers married Charlotte Johanna Cloete on 27th July 1818. This marriage gave Harry entry into Cape Dutch high society. Charlotte (1788 - 1869) was the eldest child of Pieter Lourens Cloete and the sister of the distinguished Major General Sir Abraham Josias Cloete KCB, a long-serving senior Cape Dutch officer in the British Army. There were three sons from Harry and Charlotte's marriage: Josiah Charles Rivers (1819) afterwards Chief Magistrate of Cape Town and later of Wynberg, Francis Peter Rivers (1820), and Major General Harry Rivers (1821).

Circa 1818. Undated cover from SIMONSTOWN to CAPE TOWN addressed to Colonial Secretary Henery Alexander.

This is a very early CiC (Crown in Circle) cover from Simonstown. It was posted before Alexander died in May 1818.

The first CiC handstamps were issued to Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Simons Town and Uitenhage in 1817.

Following Albany, Rivers was transferred to Swellendam at the beginning of 1825 but his appointment was not confirmed for almost two years, most likely as a result of Bathurst’s displeasure. However, at Somerset’s insistence Rivers was eventually reinstated in the service on 14th November 1826. In Swellendam he proved popular with all classes, his administration as both landdrost, starting 1826, and after 1834, as Resident Magistrate and Civil Commissioner being one that was indulgent to the needs of the local people. His interest in the daily life of the farming community was considerable and his wife’s hospitality at the Drostdy was much appreciated.

Rivers improved roads and promoted education and the general welfare of his district. In 1837, Dr William Robertson and others in Swellendam decided to establish a mission station independent of the church and bought the farm Doornkraal for that purpose. Rivers promised his help ‘in every way’ and apparently gave it generously. On 20th August 1838 he was asked to allow the site to be named after him. He agreed but preferred Riversdale to the suggested Riversville, so as to please both English and Dutch communities

On 21 June 1842 he was appointed Treasurer of the Cape Colony. He was given the additional appointment of Paymaster-General in 1851. By now he was widely trusted as an administrator but was overshadowed on the Executive Council. He helped with the drafting of the Constitution of 1853. Under the parliamentary Constitution introduced in 1854, the Treasurer-General was an ex officio member entitled to sit in both Houses but not to vote. He had previously been a member of the nominated Legislative Council, being on good terms with the ‘Easterners’ after having approved that the seat of Easten Cape government be Grahamstown. In 1854 Rivers became chairman of the Prisons Commission. He died in Cape Town in 1861, his wife in 1869.

Quote from Steve on January 26, 2026, 10:49 amSir John Wylde, Chief Justice, Cape of Good Hope

Sir John Wylde (or Wilde, 11 May 1781 – 13 December 1859, Cape Town) was Chief Justice of the Cape Colony, Cape of Good Hope and a judge of the Supreme Court of the colony of New South Wales, a time when 'Australia', not yet a country, was still a penal colony. (Australia only ceased to be a penal colony in 1868 though different colonies phased out the practice before this final date.)

Whe Wyle was born in 1781 i was the height of the "Bloody Code". British law (specifically in England and Wales) prescribed the death penalty for over 160 offences. By the late 18th century, this number was rapidly increasing, rising from roughly 50 capital crimes in 1688 to around 160 by 1765, and over 200 by the early 19th century. Those transported to Australia for petty crime got off lightly!

Wylde was born in Warwick Square, Newgate Street, London, and came from a family of lawyers. (Newgate Prison stood in London for over 700 years - 1188 to 1902 - and was notorious for being an overcrowded and brutal penal institutions It was the primary location where innocent Londoners, common and high-profile criminals and debtors awaited trial before execution or transportation.)

Having met with some success as a London barrister, Wylde accepted the position of Deputy Judge Advocate of New South Wales in 1815 with a salary of approximately £1200 per annum. He arrived in Sydney 'free' per the ship 'Elizabeth' with his family including his brother-in-law and clerk Joshua John Moore and his father Thomas Wylde whom he recommended as Clerk of the Peace. From 1816 he was active as the Deputy Judge Advocate of New South Wales and was appointed to the Vice Admiralty Court.

Wylde drafted the charter of the Bank of New South Wales and was active in its foundation in 1817. He advocated for the establishment of the Supreme Court in Van Diemen's Land. In 1824 he became judge of the old Supreme Court until the new court opened in May. He discharged his duties faithfully and properly, and at times, revolutionised several of the statutes of the courts and legal system in the new colony. Unsurprisingly for a man of his time and class he did not allow convict attorneys to practise in his court.

He was involved in the Agricultural Association and was president of the Benevolent Society, receiving several land grants. In 1821, Wylde produced a report on the judicial and legal state and process of its establishment in the new colony. This report described at length the need for the laws of New South Wales to be modified so that they would be in near parallel with those of England. This report and with the way Wylde conducted his judicial duties were fiercely criticised. He left for England in 1825 where he was knighted in 1827.

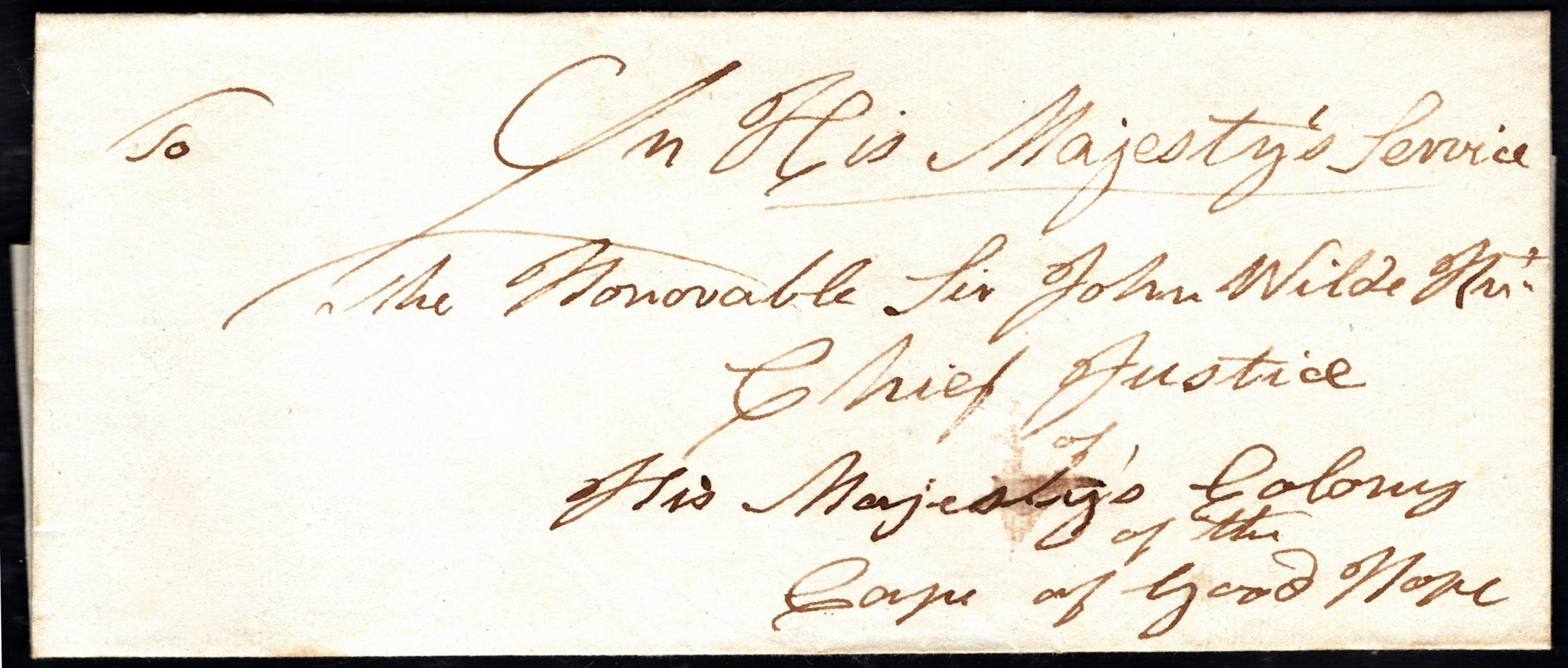

Circa 1827 - 1838. Cape of Good Hope OHMS stampless wrapper. Addressed to Sir John Wilde , the Chief Justice.

Our thanks to Kenny Napier for this. To get on his auction list, click here.He was soon appointed Chief Justice of the new court of the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. He remained in this position for the rest of his career. He presided over the abolition of slavery on 1 December 1834 and later over the beginnings of representative Cape colonial government in the early 1850s. While his work was, according to contemporary accounts, of the highest quality, his public life was beset with scandals. Today he is remembered as a weak Chief Justice, one largely ignorant of the Cape's Roman-Dutch law.

Wylde died on 13 December 1859. He never left South Africa after being appointed chief justice in Cape Town. A portrait of him, painted in 1827 by Martin Shee used to hang in the Parliament House in Cape Town.

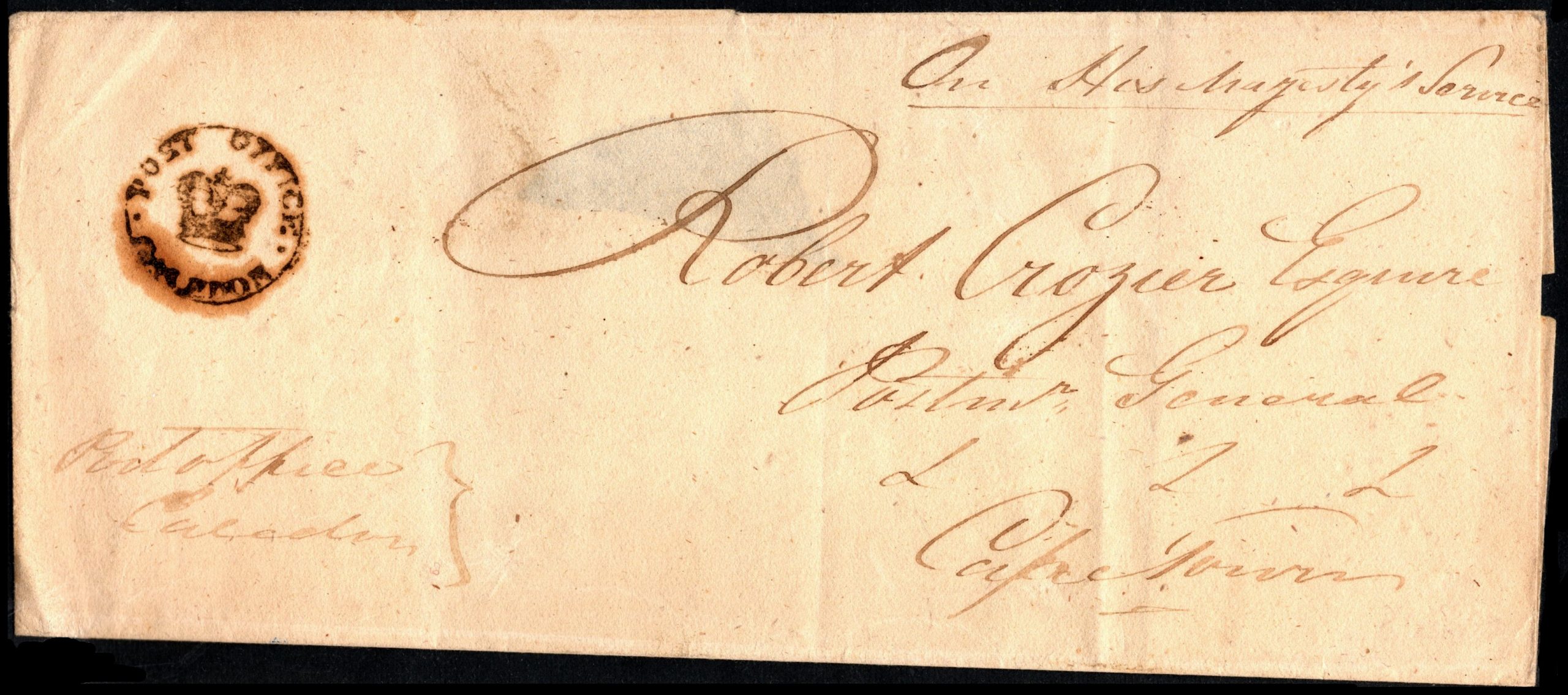

I include the following cover to Robert Crozier, Cape Postmaster General, because after the Post Office moved out of the Castle in 1809, before the introduction of the CiC (Crown in Circle) handstamp in 1818, Robert Crozier and the Post Office were installed in the renovated Old Slave Lodge, also the Court. Crozier and Wylde, if not on first name terms, would have known the other for the jobs they did.

Circa 1820. OHMS Post Office Mail. PO CALEDON writing to Robert Crozier, Postmaster General, Cape Town.

Sir John Wylde, Chief Justice, Cape of Good Hope

Sir John Wylde (or Wilde, 11 May 1781 – 13 December 1859, Cape Town) was Chief Justice of the Cape Colony, Cape of Good Hope and a judge of the Supreme Court of the colony of New South Wales, a time when 'Australia', not yet a country, was still a penal colony. (Australia only ceased to be a penal colony in 1868 though different colonies phased out the practice before this final date.)

Whe Wyle was born in 1781 i was the height of the "Bloody Code". British law (specifically in England and Wales) prescribed the death penalty for over 160 offences. By the late 18th century, this number was rapidly increasing, rising from roughly 50 capital crimes in 1688 to around 160 by 1765, and over 200 by the early 19th century. Those transported to Australia for petty crime got off lightly!

Wylde was born in Warwick Square, Newgate Street, London, and came from a family of lawyers. (Newgate Prison stood in London for over 700 years - 1188 to 1902 - and was notorious for being an overcrowded and brutal penal institutions It was the primary location where innocent Londoners, common and high-profile criminals and debtors awaited trial before execution or transportation.)

Having met with some success as a London barrister, Wylde accepted the position of Deputy Judge Advocate of New South Wales in 1815 with a salary of approximately £1200 per annum. He arrived in Sydney 'free' per the ship 'Elizabeth' with his family including his brother-in-law and clerk Joshua John Moore and his father Thomas Wylde whom he recommended as Clerk of the Peace. From 1816 he was active as the Deputy Judge Advocate of New South Wales and was appointed to the Vice Admiralty Court.

Wylde drafted the charter of the Bank of New South Wales and was active in its foundation in 1817. He advocated for the establishment of the Supreme Court in Van Diemen's Land. In 1824 he became judge of the old Supreme Court until the new court opened in May. He discharged his duties faithfully and properly, and at times, revolutionised several of the statutes of the courts and legal system in the new colony. Unsurprisingly for a man of his time and class he did not allow convict attorneys to practise in his court.

He was involved in the Agricultural Association and was president of the Benevolent Society, receiving several land grants. In 1821, Wylde produced a report on the judicial and legal state and process of its establishment in the new colony. This report described at length the need for the laws of New South Wales to be modified so that they would be in near parallel with those of England. This report and with the way Wylde conducted his judicial duties were fiercely criticised. He left for England in 1825 where he was knighted in 1827.

Circa 1827 - 1838. Cape of Good Hope OHMS stampless wrapper. Addressed to Sir John Wilde , the Chief Justice.

Our thanks to Kenny Napier for this. To get on his auction list, click here.

He was soon appointed Chief Justice of the new court of the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. He remained in this position for the rest of his career. He presided over the abolition of slavery on 1 December 1834 and later over the beginnings of representative Cape colonial government in the early 1850s. While his work was, according to contemporary accounts, of the highest quality, his public life was beset with scandals. Today he is remembered as a weak Chief Justice, one largely ignorant of the Cape's Roman-Dutch law.

Wylde died on 13 December 1859. He never left South Africa after being appointed chief justice in Cape Town. A portrait of him, painted in 1827 by Martin Shee used to hang in the Parliament House in Cape Town.

I include the following cover to Robert Crozier, Cape Postmaster General, because after the Post Office moved out of the Castle in 1809, before the introduction of the CiC (Crown in Circle) handstamp in 1818, Robert Crozier and the Post Office were installed in the renovated Old Slave Lodge, also the Court. Crozier and Wylde, if not on first name terms, would have known the other for the jobs they did.

Circa 1820. OHMS Post Office Mail. PO CALEDON writing to Robert Crozier, Postmaster General, Cape Town.