Dead Countries of Southern Africa

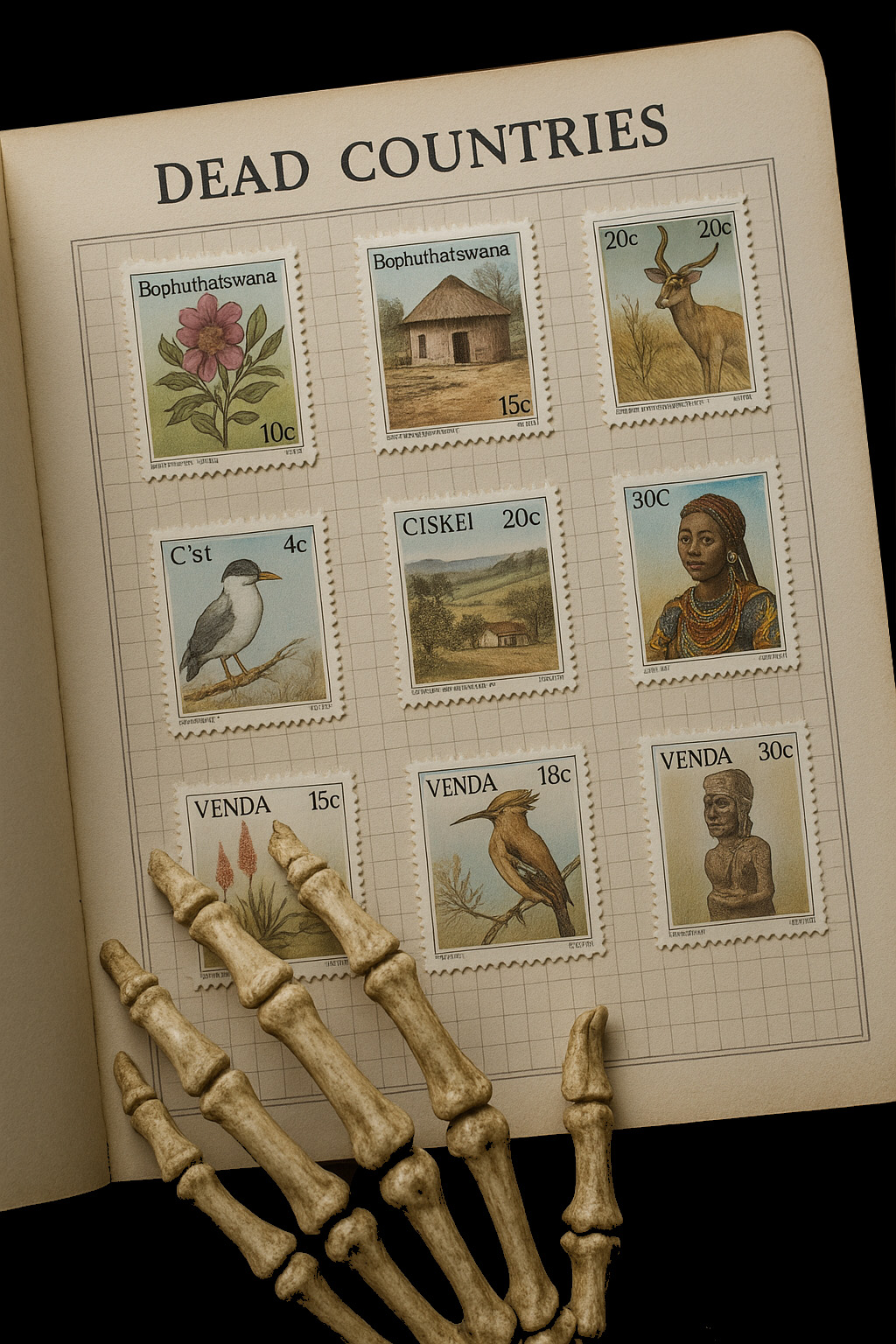

Quote from Steve on August 18, 2025, 6:55 pmCharles Abbot was a senior philatelist who lived in Pinelands, the Cape Town suburb where I grew up. Among Charles' philatelic interests was 'Orchids on Stamps'. By 1995 Charles had written up every Orchid stamp listed in Gibbons. One day when I was visiting him he gave me his complete collection of mint Homeland stamps. "Here", he said. "You can have these. I don't collect dead countries."

2025. 'Dead Countries. Some Stamps of the South African Homelands'. (Copyright. Steve Hannath).

ChatGPT AI Image created automatically in less than 5 minutes with single, simple instruction.

Note that there are issues with some of the stamps which were not expected to be accurate.

AI ain't perfect yet but it does give a surprisingly good result sometimes.I gratefully accepted Charles' gift despite the fact that I was never a fan of the Apartheid years and had a visceral dislike of the RSA stamps of that awful time. I easily understood why the Homelands stamps were 'dead countries". They were the product of colonialism and Apartheid, an attempt to create rural 'native reserves' which could supply cheap migrant labour to White South Africa. Despite the Homelands of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei never being recognised internationally, their stamps were valid on international mail. With the advent of democracy the Homelands were re-incorporated into the Republic on 27th April 1994. At this point they ceased to issue their own stamps. This was the act that defined them as 'dead countries'.

However, I suspect that Charles's understanding of what a "philatelically 'dead country'" was was as half-baked as my own. He and I both correctly assumed that because the Homelands had disappeared and were no longer issuing stamps that they were now philatelically dead countries. However, Charles maintained that he specifically did not ""collect dead countries". However, both he and I continued to collect the Cape Colony and the Union of South Africa, both of which meet all the criteria for a technically philatelically dead country. Somehow we were unable to see this. It took me years to realise this fact. I still wonder why we failed to join up the dots!

According to Grok, "a philatelically 'dead country' refers to an entity (the country or authority) that once issued postage stamps but which no longer exists as a stamp-issuing authority due to geopolitical changes, such as dissolution, annexation, or merger into another country or countries". The stamps of dead countries are not worthless as they offer the collector historical insights into vanished nations, colonies or occupations, etc. The Homelands were crudely cut out of South Africa and partitioned as 'independent' countries, a legal position rejected by the international community. Post-Apartheid, the Homelands were reincorporated into South Africa on 27th April 1994. Today the Homelands (aka 'Bantustans') are philatelically 'dead countries'.

I admit to a degree of ignorance about what made countries philatelically dead. Back in 1995 when Charles gave me his Homeland collection it seemed obvious because politically they were dead and buried. Sadly, I did not extend this awareness to other areas of South African philately, for example the Cape which I was then busily collecting and imagining it was vibrant and alive (within me at least!). Somehow I thought, (without thinking about it), that the Cape was part of the continuum of South African philately. But it wasn't. The term "philatelically dead countries" refers to entities that no longer exist as independent postal administrations because they have been absorbed, merged, or otherwise ceased to issue their own postage stamps. By this definition the Cape and every other South African state or colony listed in Stanley Gibbons and the SACC (South African Colour Catalogue) are effectively 'dead countries'!

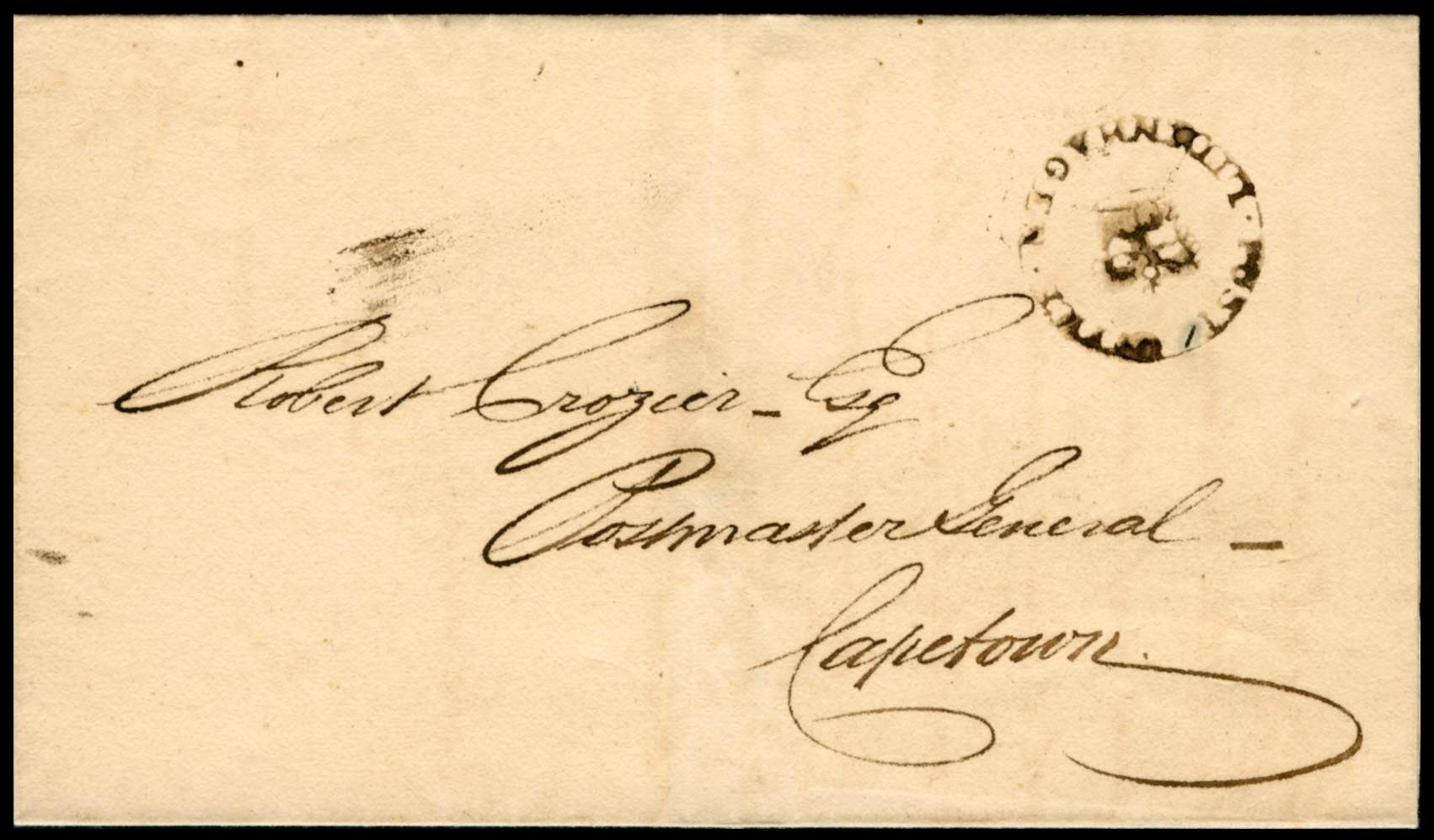

Circa 1820. Cape Wrapper. UITENHAGE to CAPE TOWN.

Endorsed with slightly-worn looking Crown-in-Circle handstamp issued 1817.

Addressed to Postmaster-General Robert Crozier, the Cape Post Office's longest serving PMG (1810 - 1850).

Dead Country Postal History.To save you having to read any further, with the exception of the countries that are still issuing stamps - the Republic of South Africa, Namibia. Zimbabwe. Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland - all the historic entities listed in the stamp catalogues of Stanley Gibbons, Scott or SACC are philatelically 'dead countries'. If you collect any country not issuing stamps today, it's a dead country!

Colonies and States of 19th Century South Africa

The colonial experience of the Cape began with the arrival of the Dutch in 1652. It was only in 1792 that it started a post office, one that did not issue stamps and likely did not use handstamps to mark letters destined for overseas delivery. As the Dutch colony did not issue stamps, it cannot truly be said to be a philatelically dead country. However, as it no longer exists, I assume it is profoundly dead!

The Cape Colony (1806 - 1910) was a distinct British colony with its own postal system and stamp issues until it was incorporated into the Union of South Africa in 1910, after which it ceased to issue its own stamps. In 1910, the Cape Colony, along with the Transvaal, Natal, and Orange River Colony united to form the Union of South Africa. The Cape Colony’s postal administration was integrated into the Union’s postal system, and its stamps remained valid until demonetized on 31st December 1937.

The Cape Colony itself became the Cape Province, losing its status as a distinct postal entity. In philatelic catalogues and collections, such as those by Stanley Gibbons, SACC or Scott, the Cape of Good Hope is treated as a distinct entity with its own stamp issues, separate from other colonies or states and the Union of South Africa because it no longer exists as an independent postal authority. The key criterion for the Cape's inclusion in a 'dead country' list is the cessation of new stamp issues under its own name after 1910.

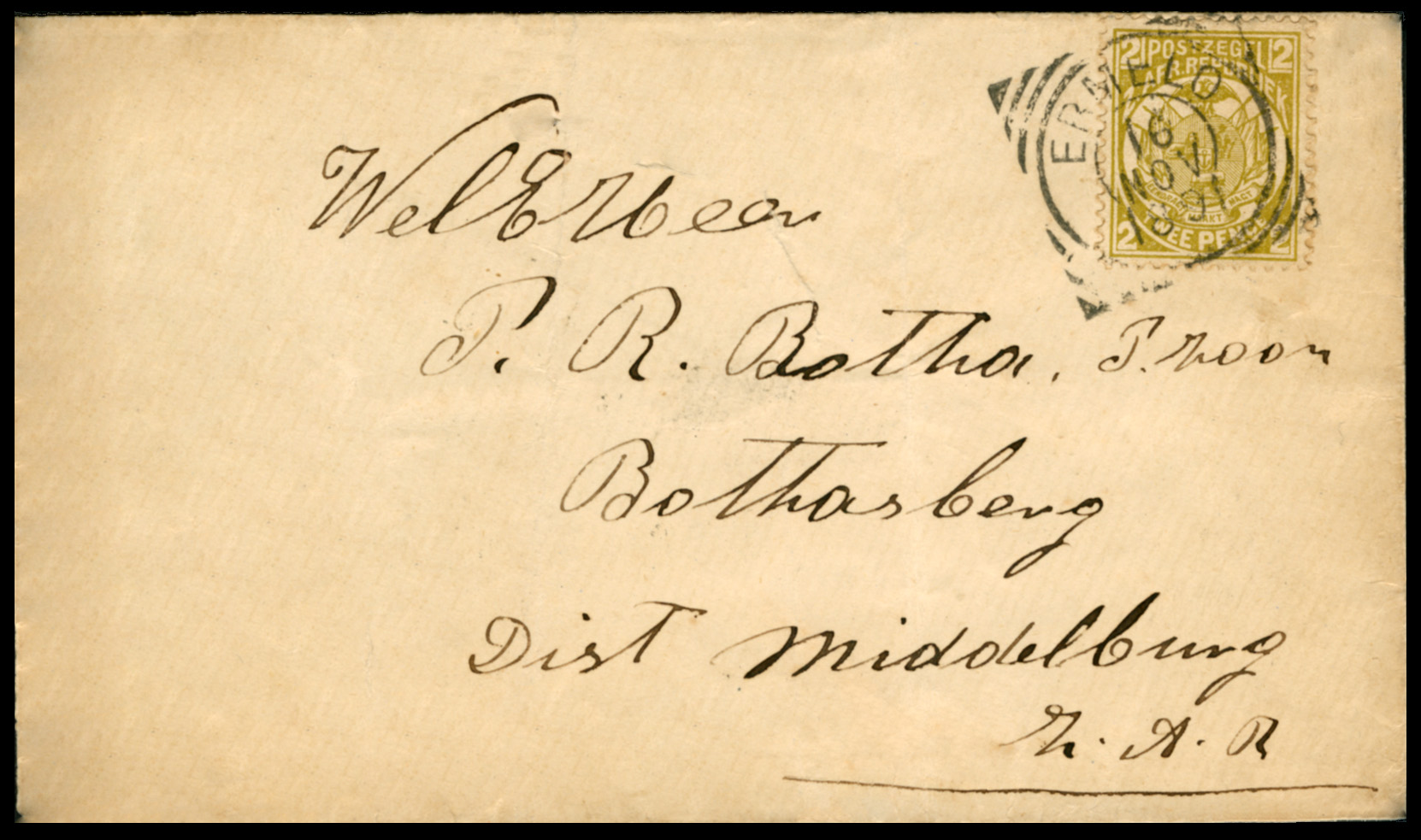

1891. Cover reverse. ZAR 1887 2d olive bistre Vurtheim cancelled ERMELO '16 NOV 1891'.

Although a relatively simple cover, this is a remarkable survivor.

MuchZAR Postal History was destroyed when the British Army burned Boer farms down during the SA War.

The defeat of the Boer Republics saw the end of OFS and ZAR stamps issues and postal administrations.

Dead Country Postal History.

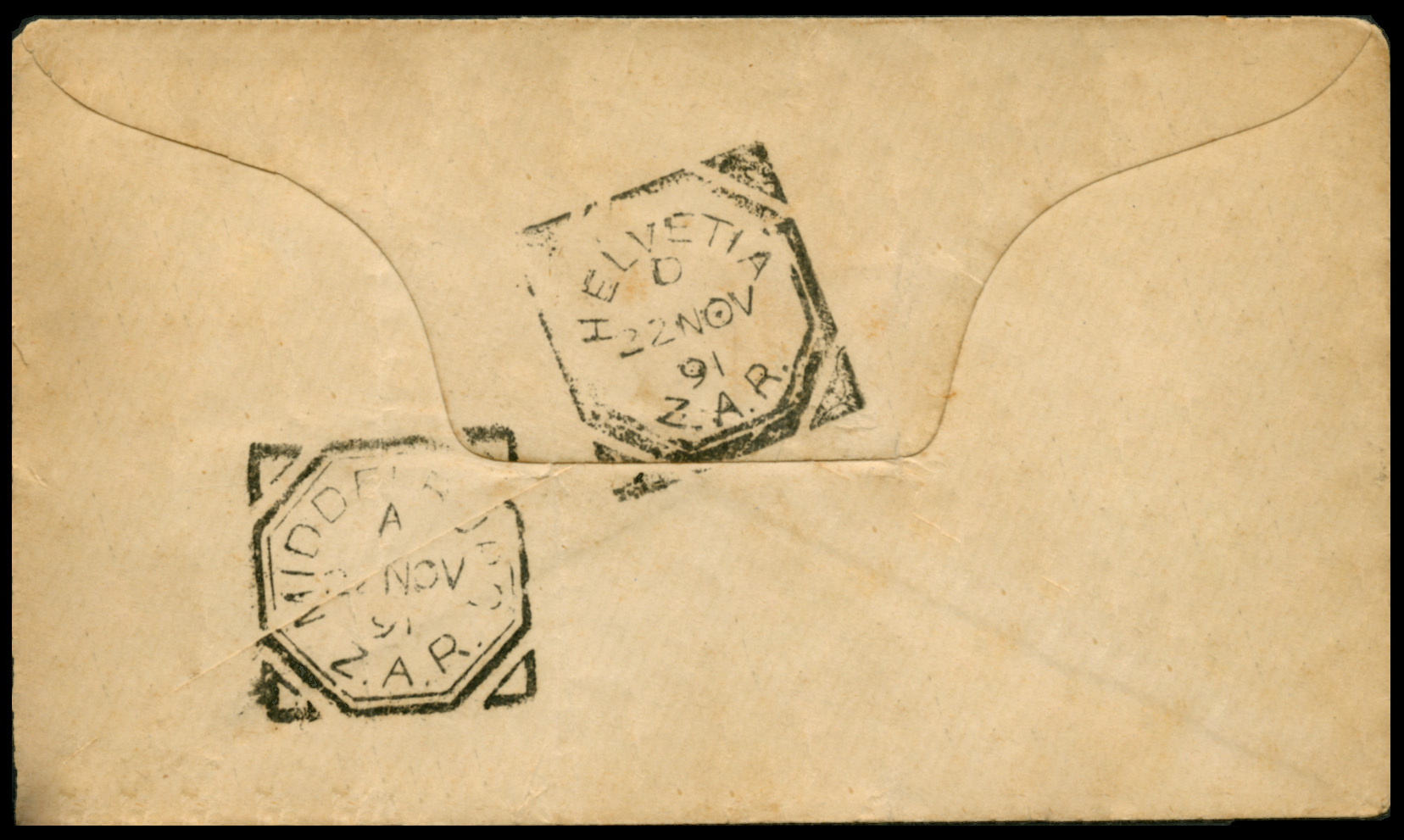

1891. Cover reverse. ZAR. Transitted HELVETIA '22 NOV 91' to MIDDELBURG '22 NOV 91'.

Dead Country Postal History.These criteria apply equally to other southern African entities like Natal, the Orange Free State / Orange River Colony and the ZAR (South African Republic) / Transvaal Colony, Griqualand West, Vryburg, New Republic and Zululand. None of these continue to exist as an independent postal authority. All meet the key criteria for inclusion in a 'dead country' list due to their incorporation into the Union of South Africa in 1910 and their cessation of new stamp issues under the old state or colony name.

The sames rules apply to the entities that made up German South West Africa, South West Africa, the British South Africa Company, Southern Rhodesia, Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Rhodesia. All are dead, dead, dead!

The Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (1910 - 1961) is also a philatelically dead country as it no longer issues postage stamps under its name or political status due to its change to a republican entity in 1961. The Union of South Africa, formed on 31st May 1910 as a self-governing dominion of the British Empire. It ceased to exist as a distinct political entity on 31st May 1961 when it became the Republic of South Africa. Philatelically, the Union of South Africa issued stamps from 1910 until 1961, starting with the 2½d stamp commemorating the 'Opening of Parliament'. After 1961, the Republic of South Africa began issuing its own republican stamps. These marked the end of the Union’s stamp-issuing period, thereby making it a dead country in philatelic terms.

Basutoland and Bechuanaland

Basutoland and Basutoland are dead countries. Their successors, Lesotho and Botswana, are not.

Basutoland, a British protectorate (modern-day Lesotho), had a distinct postal administration that began issuing its own postage stamps in 1933, inscribed "Basutoland," though earlier, from 1871 to 1933, it used stamps of the Cape Colony, Orange Free State, or Union of South Africa, depending on the period and administrative arrangements. Its postal system operated independently until Basutoland gained independence as Lesotho on 4th October 1966. Upon independence, Lesotho began issuing its own stamps and Basutoland’s postal administration ceased to exist as a separate entity. The last Basutoland stamps were issued in 1966. After independence they were replaced by Lesotho’s stamps.

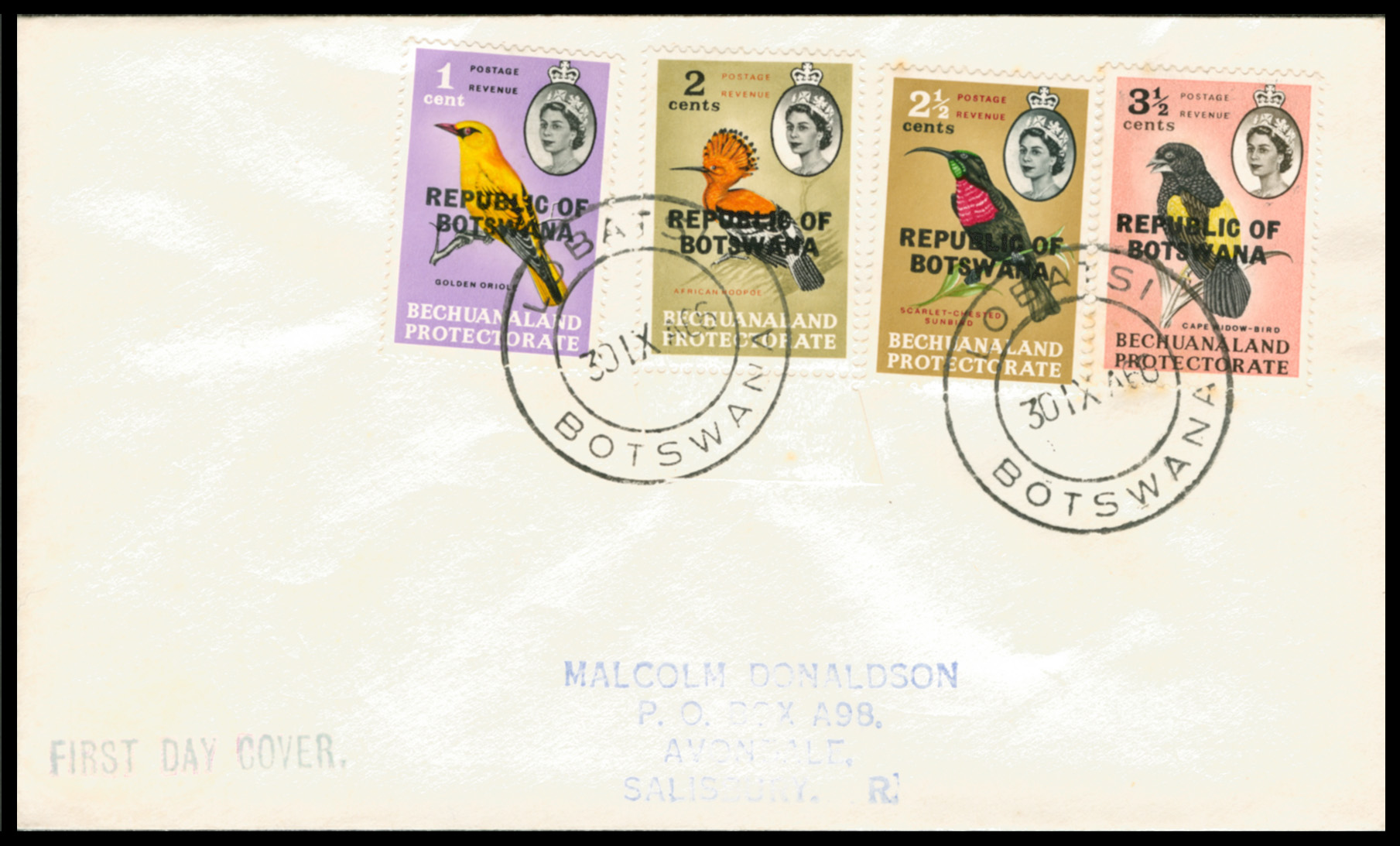

1966. FDC. Republic of Botswana overprinted on Bechuanaland Protectorate stamps cancelled LOBATSI BOTSWANA '30 iX 66'.

This overprinting of Bechuanaland Protectorate stamps by the new Botswana Republic shows it is an active philatelic country.Bechuanaland, another British protectorate (modern-day Botswana), also had its own postal administration. It issued stamps inscribed "Bechuanaland Protectorate" starting in 1932. Prior to that, from 1888, it used stamps of the Cape Colony, British Bechuanaland, or the Union of South Africa, often with overprints. Its postal system operated independently until Bechuanaland gained independence as Botswana on 30th September 1966. After independence, Botswana began issuing its own stamps, and Bechuanaland’s postal administration was discontinued. The last Bechuanaland stamps were issued in 1966. They were replaced by Botswana’s stamps post-independence. Since no new stamps have been issued under the name "Bechuanaland Protectorate" since 1966, it qualifies as a "dead country."

Swaziland

Swaziland, officially known as Eswatini since 2018, is not considered a philatelically "dead country." It has a continuous history of issuing stamps since 1889, starting with overprinted stamps from the South African Republic (ZAR / Transvaal). Swaziland issued stamps under British protection from 1933, as a self-governing state from 1967, and as an independent kingdom from 1968 to the present. Today its stamps are inscribed "Eswatini." There is no evidence that Eswatini has stopped issuing postage stamps, and it remains an active postal administration.

The change of Swaziland's name to Eswatini in 2018 left some thinking the country had ceased to exist. This name change was made to avoid confusion with Switzerland and also marked the 50th anniversary of its independence from British rule. The new name, eSwatini, is the original, pre-colonial name for the country and means "land of the Swazis" in the Swati language. The name change was a 'simple' rebranding of the same nation, not a dissolution. Unlike true "dead countries" like Zanzibar or the German Empire, Eswatini exists as a sovereign state with an active postal administration that still issues stamps.

Is Britain a philatelic dead country?

No, Britain (the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) is not considered a philatelic "dead country." The United Kingdom does not meet the required criteria. It has maintained an active and continuous postal administration since issuing the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, in 1840. It continues to issue stamps under the name "Great Britain" or "United Kingdom" to this day, with no interruption or cessation. Its most recent stamps feature King Charles III.

What about the USA?

The United States is not a philatelically dead country. It continues to actively issue postage stamps through the United States Postal Service (USPS), with new stamp designs released regularly, including commemorative issues like those for the Boston 2026 World Stamp Show. However, within the USA's philatelic history the Confederate States of America which issued its own stamps during the Civil War in the 1860s is considered a "dead country" because it no longer exists and ceased issuing stamps after the war.

Is the Republic of South Africa soon to become a philatelically 'dead country'?

Despite severe challenges facing the SAPO (South African Post Office), including financial distress and unreliable service, it continues to function as a social welfare payment and vehicle licence centre rather than as an active postal administration issuing stamps on a regular basis. In 2024 it issued just one stamp, the ‘President Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa’ issue of 16th November 2024. This coincided with the 30th Anniversary of a democratic South Africa, a period of time that saw the saw SAPO decline into near insignificance.

SAPO admits that philatelically it has “been extremely quiet lately”. This is an understatement as all South Africa-collecting philatelists know. SAPO saysy “we are still standing strong and committed to stamps and to you. The current year has been rather slow but we’ll remedy the situation in the foreseeable future”. It sounds promising but as we have learned in recent years we will have to wait and see if SAPO can deliver 10% of what it promises. It's constant failures have created the groundwork for the inevitable collapse of its postal services. However, provided SAPO Africa continues to issue one stamp a year South Africa will not be a philatelically dead country just yet!

Charles Abbot was a senior philatelist who lived in Pinelands, the Cape Town suburb where I grew up. Among Charles' philatelic interests was 'Orchids on Stamps'. By 1995 Charles had written up every Orchid stamp listed in Gibbons. One day when I was visiting him he gave me his complete collection of mint Homeland stamps. "Here", he said. "You can have these. I don't collect dead countries."

2025. 'Dead Countries. Some Stamps of the South African Homelands'. (Copyright. Steve Hannath).

ChatGPT AI Image created automatically in less than 5 minutes with single, simple instruction.

Note that there are issues with some of the stamps which were not expected to be accurate.

AI ain't perfect yet but it does give a surprisingly good result sometimes.

I gratefully accepted Charles' gift despite the fact that I was never a fan of the Apartheid years and had a visceral dislike of the RSA stamps of that awful time. I easily understood why the Homelands stamps were 'dead countries". They were the product of colonialism and Apartheid, an attempt to create rural 'native reserves' which could supply cheap migrant labour to White South Africa. Despite the Homelands of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei never being recognised internationally, their stamps were valid on international mail. With the advent of democracy the Homelands were re-incorporated into the Republic on 27th April 1994. At this point they ceased to issue their own stamps. This was the act that defined them as 'dead countries'.

However, I suspect that Charles's understanding of what a "philatelically 'dead country'" was was as half-baked as my own. He and I both correctly assumed that because the Homelands had disappeared and were no longer issuing stamps that they were now philatelically dead countries. However, Charles maintained that he specifically did not ""collect dead countries". However, both he and I continued to collect the Cape Colony and the Union of South Africa, both of which meet all the criteria for a technically philatelically dead country. Somehow we were unable to see this. It took me years to realise this fact. I still wonder why we failed to join up the dots!

According to Grok, "a philatelically 'dead country' refers to an entity (the country or authority) that once issued postage stamps but which no longer exists as a stamp-issuing authority due to geopolitical changes, such as dissolution, annexation, or merger into another country or countries". The stamps of dead countries are not worthless as they offer the collector historical insights into vanished nations, colonies or occupations, etc. The Homelands were crudely cut out of South Africa and partitioned as 'independent' countries, a legal position rejected by the international community. Post-Apartheid, the Homelands were reincorporated into South Africa on 27th April 1994. Today the Homelands (aka 'Bantustans') are philatelically 'dead countries'.

I admit to a degree of ignorance about what made countries philatelically dead. Back in 1995 when Charles gave me his Homeland collection it seemed obvious because politically they were dead and buried. Sadly, I did not extend this awareness to other areas of South African philately, for example the Cape which I was then busily collecting and imagining it was vibrant and alive (within me at least!). Somehow I thought, (without thinking about it), that the Cape was part of the continuum of South African philately. But it wasn't. The term "philatelically dead countries" refers to entities that no longer exist as independent postal administrations because they have been absorbed, merged, or otherwise ceased to issue their own postage stamps. By this definition the Cape and every other South African state or colony listed in Stanley Gibbons and the SACC (South African Colour Catalogue) are effectively 'dead countries'!

Circa 1820. Cape Wrapper. UITENHAGE to CAPE TOWN.

Endorsed with slightly-worn looking Crown-in-Circle handstamp issued 1817.

Addressed to Postmaster-General Robert Crozier, the Cape Post Office's longest serving PMG (1810 - 1850).

Dead Country Postal History.

To save you having to read any further, with the exception of the countries that are still issuing stamps - the Republic of South Africa, Namibia. Zimbabwe. Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland - all the historic entities listed in the stamp catalogues of Stanley Gibbons, Scott or SACC are philatelically 'dead countries'. If you collect any country not issuing stamps today, it's a dead country!

Colonies and States of 19th Century South Africa

The colonial experience of the Cape began with the arrival of the Dutch in 1652. It was only in 1792 that it started a post office, one that did not issue stamps and likely did not use handstamps to mark letters destined for overseas delivery. As the Dutch colony did not issue stamps, it cannot truly be said to be a philatelically dead country. However, as it no longer exists, I assume it is profoundly dead!

The Cape Colony (1806 - 1910) was a distinct British colony with its own postal system and stamp issues until it was incorporated into the Union of South Africa in 1910, after which it ceased to issue its own stamps. In 1910, the Cape Colony, along with the Transvaal, Natal, and Orange River Colony united to form the Union of South Africa. The Cape Colony’s postal administration was integrated into the Union’s postal system, and its stamps remained valid until demonetized on 31st December 1937.

The Cape Colony itself became the Cape Province, losing its status as a distinct postal entity. In philatelic catalogues and collections, such as those by Stanley Gibbons, SACC or Scott, the Cape of Good Hope is treated as a distinct entity with its own stamp issues, separate from other colonies or states and the Union of South Africa because it no longer exists as an independent postal authority. The key criterion for the Cape's inclusion in a 'dead country' list is the cessation of new stamp issues under its own name after 1910.

1891. Cover reverse. ZAR 1887 2d olive bistre Vurtheim cancelled ERMELO '16 NOV 1891'.

Although a relatively simple cover, this is a remarkable survivor.

MuchZAR Postal History was destroyed when the British Army burned Boer farms down during the SA War.

The defeat of the Boer Republics saw the end of OFS and ZAR stamps issues and postal administrations.

Dead Country Postal History.

1891. Cover reverse. ZAR. Transitted HELVETIA '22 NOV 91' to MIDDELBURG '22 NOV 91'.

Dead Country Postal History.

These criteria apply equally to other southern African entities like Natal, the Orange Free State / Orange River Colony and the ZAR (South African Republic) / Transvaal Colony, Griqualand West, Vryburg, New Republic and Zululand. None of these continue to exist as an independent postal authority. All meet the key criteria for inclusion in a 'dead country' list due to their incorporation into the Union of South Africa in 1910 and their cessation of new stamp issues under the old state or colony name.

The sames rules apply to the entities that made up German South West Africa, South West Africa, the British South Africa Company, Southern Rhodesia, Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Rhodesia. All are dead, dead, dead!

The Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (1910 - 1961) is also a philatelically dead country as it no longer issues postage stamps under its name or political status due to its change to a republican entity in 1961. The Union of South Africa, formed on 31st May 1910 as a self-governing dominion of the British Empire. It ceased to exist as a distinct political entity on 31st May 1961 when it became the Republic of South Africa. Philatelically, the Union of South Africa issued stamps from 1910 until 1961, starting with the 2½d stamp commemorating the 'Opening of Parliament'. After 1961, the Republic of South Africa began issuing its own republican stamps. These marked the end of the Union’s stamp-issuing period, thereby making it a dead country in philatelic terms.

Basutoland and Bechuanaland

Basutoland and Basutoland are dead countries. Their successors, Lesotho and Botswana, are not.

Basutoland, a British protectorate (modern-day Lesotho), had a distinct postal administration that began issuing its own postage stamps in 1933, inscribed "Basutoland," though earlier, from 1871 to 1933, it used stamps of the Cape Colony, Orange Free State, or Union of South Africa, depending on the period and administrative arrangements. Its postal system operated independently until Basutoland gained independence as Lesotho on 4th October 1966. Upon independence, Lesotho began issuing its own stamps and Basutoland’s postal administration ceased to exist as a separate entity. The last Basutoland stamps were issued in 1966. After independence they were replaced by Lesotho’s stamps.

1966. FDC. Republic of Botswana overprinted on Bechuanaland Protectorate stamps cancelled LOBATSI BOTSWANA '30 iX 66'.

This overprinting of Bechuanaland Protectorate stamps by the new Botswana Republic shows it is an active philatelic country.

Bechuanaland, another British protectorate (modern-day Botswana), also had its own postal administration. It issued stamps inscribed "Bechuanaland Protectorate" starting in 1932. Prior to that, from 1888, it used stamps of the Cape Colony, British Bechuanaland, or the Union of South Africa, often with overprints. Its postal system operated independently until Bechuanaland gained independence as Botswana on 30th September 1966. After independence, Botswana began issuing its own stamps, and Bechuanaland’s postal administration was discontinued. The last Bechuanaland stamps were issued in 1966. They were replaced by Botswana’s stamps post-independence. Since no new stamps have been issued under the name "Bechuanaland Protectorate" since 1966, it qualifies as a "dead country."

Swaziland

Swaziland, officially known as Eswatini since 2018, is not considered a philatelically "dead country." It has a continuous history of issuing stamps since 1889, starting with overprinted stamps from the South African Republic (ZAR / Transvaal). Swaziland issued stamps under British protection from 1933, as a self-governing state from 1967, and as an independent kingdom from 1968 to the present. Today its stamps are inscribed "Eswatini." There is no evidence that Eswatini has stopped issuing postage stamps, and it remains an active postal administration.

The change of Swaziland's name to Eswatini in 2018 left some thinking the country had ceased to exist. This name change was made to avoid confusion with Switzerland and also marked the 50th anniversary of its independence from British rule. The new name, eSwatini, is the original, pre-colonial name for the country and means "land of the Swazis" in the Swati language. The name change was a 'simple' rebranding of the same nation, not a dissolution. Unlike true "dead countries" like Zanzibar or the German Empire, Eswatini exists as a sovereign state with an active postal administration that still issues stamps.

Is Britain a philatelic dead country?

No, Britain (the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) is not considered a philatelic "dead country." The United Kingdom does not meet the required criteria. It has maintained an active and continuous postal administration since issuing the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, in 1840. It continues to issue stamps under the name "Great Britain" or "United Kingdom" to this day, with no interruption or cessation. Its most recent stamps feature King Charles III.

What about the USA?

The United States is not a philatelically dead country. It continues to actively issue postage stamps through the United States Postal Service (USPS), with new stamp designs released regularly, including commemorative issues like those for the Boston 2026 World Stamp Show. However, within the USA's philatelic history the Confederate States of America which issued its own stamps during the Civil War in the 1860s is considered a "dead country" because it no longer exists and ceased issuing stamps after the war.

Is the Republic of South Africa soon to become a philatelically 'dead country'?

Despite severe challenges facing the SAPO (South African Post Office), including financial distress and unreliable service, it continues to function as a social welfare payment and vehicle licence centre rather than as an active postal administration issuing stamps on a regular basis. In 2024 it issued just one stamp, the ‘President Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa’ issue of 16th November 2024. This coincided with the 30th Anniversary of a democratic South Africa, a period of time that saw the saw SAPO decline into near insignificance.

SAPO admits that philatelically it has “been extremely quiet lately”. This is an understatement as all South Africa-collecting philatelists know. SAPO saysy “we are still standing strong and committed to stamps and to you. The current year has been rather slow but we’ll remedy the situation in the foreseeable future”. It sounds promising but as we have learned in recent years we will have to wait and see if SAPO can deliver 10% of what it promises. It's constant failures have created the groundwork for the inevitable collapse of its postal services. However, provided SAPO Africa continues to issue one stamp a year South Africa will not be a philatelically dead country just yet!

Quote from Steve on August 19, 2025, 4:42 pmHave any philatelically dead countries come back to life?

The possibility exists that the Western Cape of South Africa may one day (soon hopefully!) become independent. Many of its inhabitants are disillusioned with the ANC and its disastrous inabilty to run a First World economy. Ideological policies, like Black Economic Empowerment, fail to encourage foreign investment. Rampant corruption and gravy-train gangsterism runs riot. Iranian funding is used by the ANC to fight elections. The country is moving away from core Western values and democratic principles. The clamour for a referendum to decide the Western Cape's independence from Tshwete (Pretoria) is now louder and more popular than ever.

If the Western Cape became independent, would it be a philatelically dead country come back to life?

In philately, a "dead country" refers to a stamp-issuing entity (country) that no longer exists or has ceased issuing stamps, often due to geopolitical changes like dissolution, annexation, or merger. The concept of a philatelically "dead" country coming "back to life" implies that the entity that stopped issuing stamps under its former identity later resumes issuing stamps, either as a re-established entity or under a new but related identity. So, yes, there are few philatelically "dead" countries that have come back to life by resuming stamp issuance, typically after regaining independence or re-establishing a distinct postal identity.

However, the Western Cape is unlikely to be a dead country come back to life. The Cape Colony previously covered a huge area. some 600,000 square km. The Western Cape province occupies a much smaller area of some 130,000 square km. Therefore, an independent Western Cape will not return as the original Cape Colony or Province but rather as a small rump section of the older entity. Whatever the name of this small new country or entity its stamps would not be the successors to those of the Cape Colony, no matter what name it used. A likely choice may be the Republic of the Western Cape.

Notable examples of dead countries come back to life include Armenia, Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia,the successor states of Yugoslavia (e.g., Serbia) and the Ukraine. Zanzibar represents a partial revival due to its semi-autonomous status. These cases reflect the dynamic nature of geopolitics and philately, where historical changes can lead to both the "death" and "rebirth" of stamp-issuing entities. For collectors, these revived countries offer a fascinating intersection of history and philately, with their early stamps valued as "dead country" items and their modern issues symbolizing their resurgence.

Based on available information, there are cases where countries or entities that were once considered philatelically "dead" have resumed issuing stamps, often after regaining independence or reconfiguring their political status. Below are some notable examples, focusing on historical and philatelic contexts of philatelically "dead" countries that resumed issuing stamps

The three Baltic states of Armenia, Estonia, and Latvia were independent nations issuing their own stamps in the early 20th Century (circa 1918–1920) after the collapse of the Russian Empire. However, they were absorbed into the Soviet Union by the 1920s, which led to the cessation of their stamp-issuing status, rendering them philatelically "dead." The Soviet Union issued stamps for the entire region, and these individual entities no longer produced their own. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Armenia, Estonia, and Latvia regained independence and resumed issuing their own postage stamps. This marked their philatelic "revival" as sovereign stamp-issuing nations.

As noted in a Forbes article, these countries are examples of nations that lost their stamp-issuing status during Soviet annexation but regained it post-1991, making them prime examples of "dead countries" coming back to life. Their early stamps from the 1918–1920 period are collectible as "dead country" items, while their modern stamps reflect their renewed status.

Czechoslovakia was an independent nation formed after World War I, issuing stamps from 1918 until its dissolution in 1993 into two separate countries: the Czech Republic and Slovakia. During World War II, Czechoslovakia was occupied by Nazi Germany, and its stamp-issuing status was temporarily halted, with German occupation stamps issued instead, making it philatelically "dead" during that period. After World War II, Czechoslovakia resumed issuing stamps until its peaceful split in 1993. Both the Czech Republic and Slovakia began issuing their own stamps as independent nations, effectively reviving their philatelic identities. The pre-WWII and wartime occupation stamps are considered "dead country" items, while the post-1993 stamps of the Czech Republic and Slovakia represent their philatelic revival. The split is noted in sources as a significant geopolitical change that created new stamp-issuing entities.

Yugoslavia, formed after World War I, issued stamps from the 1920s until its breakup in the 1990s. The dissolution led to the creation of several independent nations, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia, each of which began issuing their own stamps. During its existence, Yugoslavia was philatelically "alive," but its dissolution rendered it a "dead country." The successor states, particularly those like Serbia and Montenegro, which trace their historical roots to earlier entities (e.g., the Kingdom of Serbia or Montenegro, which issued stamps before joining Yugoslavia), can be seen as a form of philatelic revival. For example, the Kingdom of Serbia issued stamps in the 19th century, became part of Yugoslavia (ceasing independent stamp issuance), and then resumed issuing stamps as modern Serbia post-1990s. The stamps of pre-Yugoslavia entities like the Kingdom of Serbia are collectible as "dead country" stamps, while the modern stamps of Serbia and other successor states represent their philatelic reemergence.

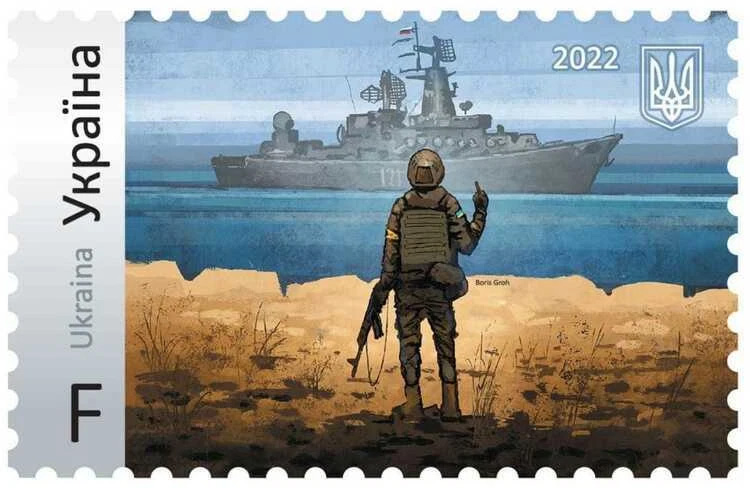

Ukraine is an example of a philatelically dead country come back to life. It issued stamps during its brief independence in 1918–1920, ceased during Soviet rule (1920–1991), and resumed with vigour after gaining independence in 1991.During the 1918 Ukrainian War of Independence, the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) issued its first postage stamps. These included the "Shag" series and overprinted Russian stamps with the Ukrainian trident (tryzub). The West Ukrainian People’s Republic (WUPR), established in 1918 in Galicia, also issued stamps. However, by 1920, Soviet forces gained control, and Ukraine was incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR). During this period, Soviet stamps were used, and Ukraine did not issue its own stamps, effectively halting its independent philatelic activity.

2022. Ukraine.'Russian Warship go F**k Yourself'.

The War's toll is 1 million Russian and 400,000 Ukrainian dead and injured, not counting civilians.

This may be the South Africa's fate if the ANC insist on holding onto the Western Cape.

Freedom, independence and 'F**k You' stamps come at a price!Following Ukraine’s declaration of independence on 24th August 1991, and its formal recognition after the 1st December 1991 referendum, Ukraine re-established its postal service under Ukrposhta. The first modern Ukrainian stamp was issued on 1st March 1992, marking the country’s return to philatelic activity. Its stamps reflect its broader national revival, reclaiming cultural and political identity through stamps that celebrate Ukrainian heritage, resilience, and resistance, especially evident in wartime issues. Unlike entities that revived philatelically but later ceased to exist, Ukraine’s ongoing stamp production and sovereignty solidify its status as a revived philatelic nation

Zanzibar is an island off the coast of East Africa. It issued stamps as a British protectorate from the 1890s until it merged with Tanganyika in 1964 to form Tanzania, at which point it ceased issuing its own stamps, becoming philatelically "dead." In recent years, Zanzibar has issued some local or commemorative stamps under the Tanzanian postal system, particularly for regional use or tourism purposes. While not fully independent, these issues reflect a partial philatelic revival tied to Zanzibar’s semi-autonomous status. Zanzibar’s early stamps are highly sought after by collectors of "dead countries," and its modern issues, though limited, indicate a resurgence of philatelic activity.

Not all dead country cases are clear-cut. For example, some entities like Iceland or Haiti are considered philatelically "dead" because they stopped issuing stamps, even though the nation still exists. Iceland announced in 2020 that it would cease issuing stamps, but if it were to resume, it could be considered a "revived" philatelic entity. Some micronations or self-proclaimed entities (e.g., Sealand) issue stamps but are not considered true "countries" in philately. These are often labeled "bogus Cinderellas" and are not typically counted as "dead countries" unless they were once recognised stamp-issuing entities.

Have any philatelically dead countries come back to life?

The possibility exists that the Western Cape of South Africa may one day (soon hopefully!) become independent. Many of its inhabitants are disillusioned with the ANC and its disastrous inabilty to run a First World economy. Ideological policies, like Black Economic Empowerment, fail to encourage foreign investment. Rampant corruption and gravy-train gangsterism runs riot. Iranian funding is used by the ANC to fight elections. The country is moving away from core Western values and democratic principles. The clamour for a referendum to decide the Western Cape's independence from Tshwete (Pretoria) is now louder and more popular than ever.

If the Western Cape became independent, would it be a philatelically dead country come back to life?

In philately, a "dead country" refers to a stamp-issuing entity (country) that no longer exists or has ceased issuing stamps, often due to geopolitical changes like dissolution, annexation, or merger. The concept of a philatelically "dead" country coming "back to life" implies that the entity that stopped issuing stamps under its former identity later resumes issuing stamps, either as a re-established entity or under a new but related identity. So, yes, there are few philatelically "dead" countries that have come back to life by resuming stamp issuance, typically after regaining independence or re-establishing a distinct postal identity.

However, the Western Cape is unlikely to be a dead country come back to life. The Cape Colony previously covered a huge area. some 600,000 square km. The Western Cape province occupies a much smaller area of some 130,000 square km. Therefore, an independent Western Cape will not return as the original Cape Colony or Province but rather as a small rump section of the older entity. Whatever the name of this small new country or entity its stamps would not be the successors to those of the Cape Colony, no matter what name it used. A likely choice may be the Republic of the Western Cape.

Notable examples of dead countries come back to life include Armenia, Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia,the successor states of Yugoslavia (e.g., Serbia) and the Ukraine. Zanzibar represents a partial revival due to its semi-autonomous status. These cases reflect the dynamic nature of geopolitics and philately, where historical changes can lead to both the "death" and "rebirth" of stamp-issuing entities. For collectors, these revived countries offer a fascinating intersection of history and philately, with their early stamps valued as "dead country" items and their modern issues symbolizing their resurgence.

Based on available information, there are cases where countries or entities that were once considered philatelically "dead" have resumed issuing stamps, often after regaining independence or reconfiguring their political status. Below are some notable examples, focusing on historical and philatelic contexts of philatelically "dead" countries that resumed issuing stamps

The three Baltic states of Armenia, Estonia, and Latvia were independent nations issuing their own stamps in the early 20th Century (circa 1918–1920) after the collapse of the Russian Empire. However, they were absorbed into the Soviet Union by the 1920s, which led to the cessation of their stamp-issuing status, rendering them philatelically "dead." The Soviet Union issued stamps for the entire region, and these individual entities no longer produced their own. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Armenia, Estonia, and Latvia regained independence and resumed issuing their own postage stamps. This marked their philatelic "revival" as sovereign stamp-issuing nations.

As noted in a Forbes article, these countries are examples of nations that lost their stamp-issuing status during Soviet annexation but regained it post-1991, making them prime examples of "dead countries" coming back to life. Their early stamps from the 1918–1920 period are collectible as "dead country" items, while their modern stamps reflect their renewed status.

Czechoslovakia was an independent nation formed after World War I, issuing stamps from 1918 until its dissolution in 1993 into two separate countries: the Czech Republic and Slovakia. During World War II, Czechoslovakia was occupied by Nazi Germany, and its stamp-issuing status was temporarily halted, with German occupation stamps issued instead, making it philatelically "dead" during that period. After World War II, Czechoslovakia resumed issuing stamps until its peaceful split in 1993. Both the Czech Republic and Slovakia began issuing their own stamps as independent nations, effectively reviving their philatelic identities. The pre-WWII and wartime occupation stamps are considered "dead country" items, while the post-1993 stamps of the Czech Republic and Slovakia represent their philatelic revival. The split is noted in sources as a significant geopolitical change that created new stamp-issuing entities.

Yugoslavia, formed after World War I, issued stamps from the 1920s until its breakup in the 1990s. The dissolution led to the creation of several independent nations, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia, each of which began issuing their own stamps. During its existence, Yugoslavia was philatelically "alive," but its dissolution rendered it a "dead country." The successor states, particularly those like Serbia and Montenegro, which trace their historical roots to earlier entities (e.g., the Kingdom of Serbia or Montenegro, which issued stamps before joining Yugoslavia), can be seen as a form of philatelic revival. For example, the Kingdom of Serbia issued stamps in the 19th century, became part of Yugoslavia (ceasing independent stamp issuance), and then resumed issuing stamps as modern Serbia post-1990s. The stamps of pre-Yugoslavia entities like the Kingdom of Serbia are collectible as "dead country" stamps, while the modern stamps of Serbia and other successor states represent their philatelic reemergence.

Ukraine is an example of a philatelically dead country come back to life. It issued stamps during its brief independence in 1918–1920, ceased during Soviet rule (1920–1991), and resumed with vigour after gaining independence in 1991.During the 1918 Ukrainian War of Independence, the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) issued its first postage stamps. These included the "Shag" series and overprinted Russian stamps with the Ukrainian trident (tryzub). The West Ukrainian People’s Republic (WUPR), established in 1918 in Galicia, also issued stamps. However, by 1920, Soviet forces gained control, and Ukraine was incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR). During this period, Soviet stamps were used, and Ukraine did not issue its own stamps, effectively halting its independent philatelic activity.

2022. Ukraine.'Russian Warship go F**k Yourself'.

The War's toll is 1 million Russian and 400,000 Ukrainian dead and injured, not counting civilians.

This may be the South Africa's fate if the ANC insist on holding onto the Western Cape.

Freedom, independence and 'F**k You' stamps come at a price!

Following Ukraine’s declaration of independence on 24th August 1991, and its formal recognition after the 1st December 1991 referendum, Ukraine re-established its postal service under Ukrposhta. The first modern Ukrainian stamp was issued on 1st March 1992, marking the country’s return to philatelic activity. Its stamps reflect its broader national revival, reclaiming cultural and political identity through stamps that celebrate Ukrainian heritage, resilience, and resistance, especially evident in wartime issues. Unlike entities that revived philatelically but later ceased to exist, Ukraine’s ongoing stamp production and sovereignty solidify its status as a revived philatelic nation

Zanzibar is an island off the coast of East Africa. It issued stamps as a British protectorate from the 1890s until it merged with Tanganyika in 1964 to form Tanzania, at which point it ceased issuing its own stamps, becoming philatelically "dead." In recent years, Zanzibar has issued some local or commemorative stamps under the Tanzanian postal system, particularly for regional use or tourism purposes. While not fully independent, these issues reflect a partial philatelic revival tied to Zanzibar’s semi-autonomous status. Zanzibar’s early stamps are highly sought after by collectors of "dead countries," and its modern issues, though limited, indicate a resurgence of philatelic activity.

Not all dead country cases are clear-cut. For example, some entities like Iceland or Haiti are considered philatelically "dead" because they stopped issuing stamps, even though the nation still exists. Iceland announced in 2020 that it would cease issuing stamps, but if it were to resume, it could be considered a "revived" philatelic entity. Some micronations or self-proclaimed entities (e.g., Sealand) issue stamps but are not considered true "countries" in philately. These are often labeled "bogus Cinderellas" and are not typically counted as "dead countries" unless they were once recognised stamp-issuing entities.