Sophiatown

Quote from Steve on August 4, 2025, 4:42 pmDepending on who you talk to Sophiatown was either the most wonderful multi-cultural melting pot in Johannesburg or it was the city's 'vrot kol', (Afr. rotten spot), an area in desperate need of restoration and or rebuilding. The truth lies somewhere in-between. What is undeniable is that Sophiatown's most important contribution to South Africa's history was its destruction under Apartheid's Group Areas Act. This political act can be traced in the postal history covers below. They provide curious South Africans with good reasons to collect postal history as a hobby.

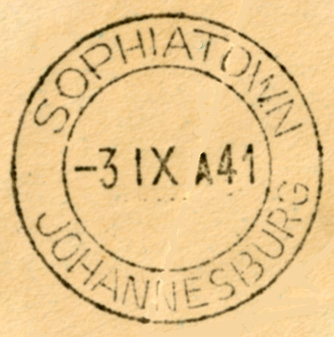

1941. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG. Putzel No. 2.

Putzel's 'The Postmarks of South Africa' list two Sophiatown Post Offices (1912 - 1915 and 1926 - 1966) using three different datestamps. The first, No. 1., the smallest at 25mm, says 'SOPHIATOWN' only with the Month in letters. Visser's Addendum lists a No. 1a 'date with block i.s.o. time code letter'. No's 2 and 3 are very similar to each other at 26mm, both saying 'SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG'. The difference lies in no. 3. having marginally larger text. Visser's Addendum lists a No. 2a 'date without time code letter'.

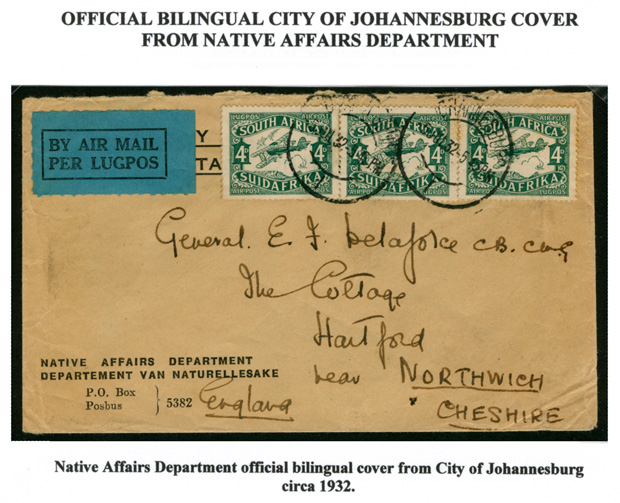

We start with a cover from the City of Johannesburg's Native Affairs Department who did not own the land on which Sophiatown was built. As a result, Sophiatown was not within the Native Affairs Department's remit. This prevented the City from taking drastic unilateral action against Sophiatown which it saw as a troublesome urban ghetto. Sophiatown would not survive after the Nationalists came to power in 1948 when they threw the entire weight of Apartheid legislation against Johannesburg's only inner-city Black suburb.

1932. Airmail cover. JOHANNESBURG '5 JUL 32' to GB.

City of Johannesburg bilingual Native Affairs Department printed envelope.

The Native Affairs Department controlled the lives of Black South Africans in Municipal townships.

It did not own the land on which Sophiatown was built and as a consequence did not maintain it.

This was one of the reasons for Sophiatown's neglected state of disrepair.

(Cover courtesy of Bob Hill.)Sophiatown was born of property speculation during Johannesburg's golden age. In 1897 Hermann Tobiansky purchased 237 acres of farmland some 4 miles west of the central Johannesburg for the purpose of creating a township. The South African War (1899 - 1902) put his plans on hold until 1903 when he had the private leasehold township surveyed and divided into almost 1700 small stands.

Tobiansky named the township after his wife, Sophia, and some of the main streets after his children. At this time, segregation existed but it was not yet set in political stone. Black South Africans still enjoyed freehold rights to owning property which they exercised within Sophiatown. The enactment of the Union's Natives Land Act, (1913) would remove this right. After the City of Johannesburg built a sewage plant nearby, wealthier property owners began to move out of Sophiatown. From 1920, its Black population increased due in large part to workers wanting to live closer to their places of employment in the City of Gold. Most rented the property they lived in.

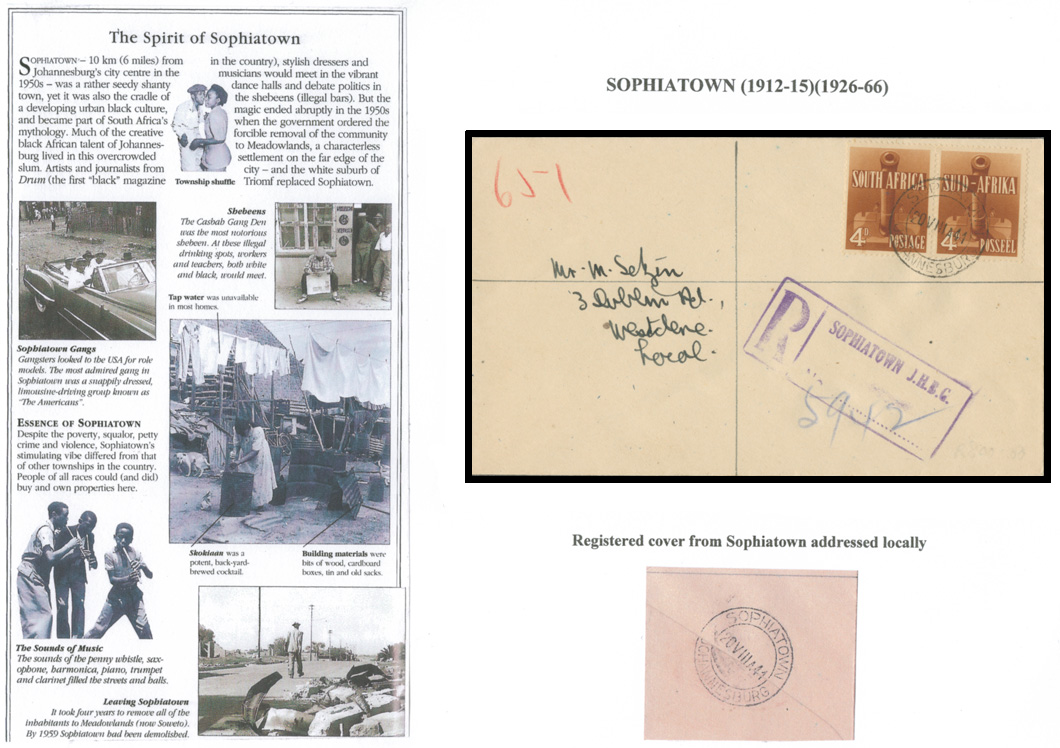

1941. Registered letter. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG '20 VIII 41' to Westdene, Local.

This letter and the following one are philatelic in origin ie. created for postal history purposes.

Westdene was a White suburb adjoining Sophiatown. The addressee was presumably the sender also.

(Display page courtesy of Bob Hill.)Although run-down, over-crowded and suffering poverty and crime, Sophiatown developed a metropolitan character that the Johannesburg City Council's abject Black township's lacked. Importantly, Black intelligentsia saw Sophiatown as a desirable place to live. It produced many South African Black writers, musicians, politicians and artists. Included among its inhabitants were colourful, street-wise 'tsotsis' (Sotho or Tswana. criminal). These criminals were romanticized in Black popular culture by Drum magazine.

One of its untruths was that Sophiatown's tsotsi underclass were noble criminals who stole only from Whites. The reality was that the tsotsi were a scourge on all who were vulnerable. In defining the new reality of African life in an urbanised, post-agricultural industrial society, Drum magazine searched for a new Black South African identity that rejected both its tribalism of the past and the White's policy of Apartheid that planned that they should perpetuate it in future tribal 'homelands'. The influence of American gangster movies in South Africa in the 1940s and 50s led Drum to find inspiration for the New South African Black Man in the Sophiatown 'tsotsi', an unwanted victim of segregation within White South Africa. Drum saw the tsotsi as an economic rebel stealing from the rich. Drum's tsotsi values would find a home among the rank and file of the ANC, South Africa's Black liberation movement, once in power.

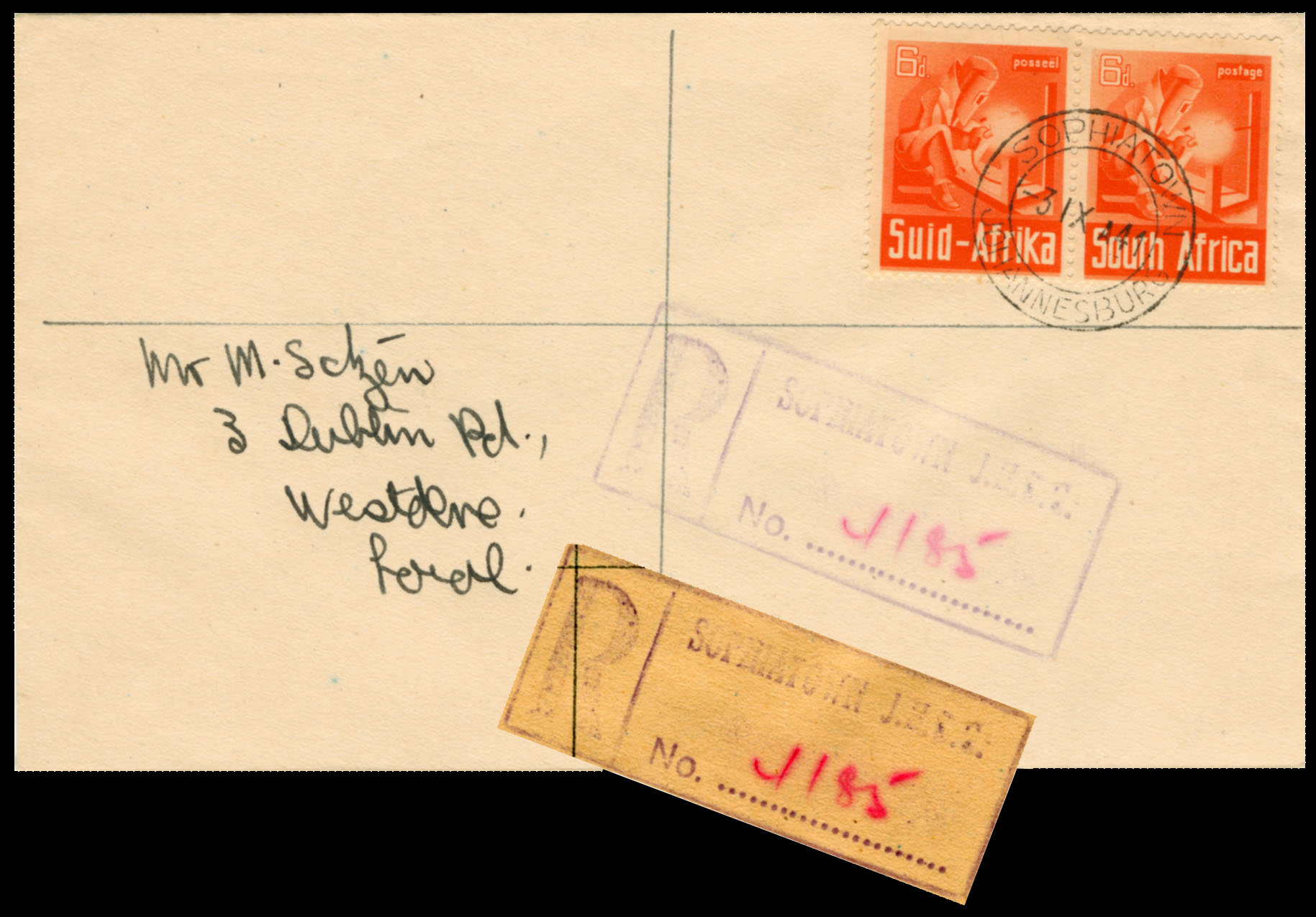

1941. Registered letter. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG '31 IXI 41' to Westdene, Local.

This letter and the preceding one are philatelic in origin ie. created for postal history purposes.

Westdene was a White suburb adjoining Sophiatown. The addressee was presumably the sender also.

The Johannesburg City Council increasingly saw Sophiatown as a Black slum too close to White Johannesburg. As early as 1944 the City Council began planning to move the residents of Sophiatown out of Johannesburg. This met with resistance and made slow progress. However in 1948 the National Party won the post-war, Whites-only election on a promise of implementing the new racist policy of Apartheid as a means of securing the country for Europeans for the next 1000 years. Among its segregationist plans was the Group Areas Act, the Immorality Amendment Act, (both of 1950), and the Native Resettlement Act of 1954, all of which empowered the Nationalists to stop people of different races from living and or sleeping together. Each 'group' now had to live in areas zoned exclusively for them. Mixed residential areas were destroyed and replaced by zones of uniform urban racial segregation.

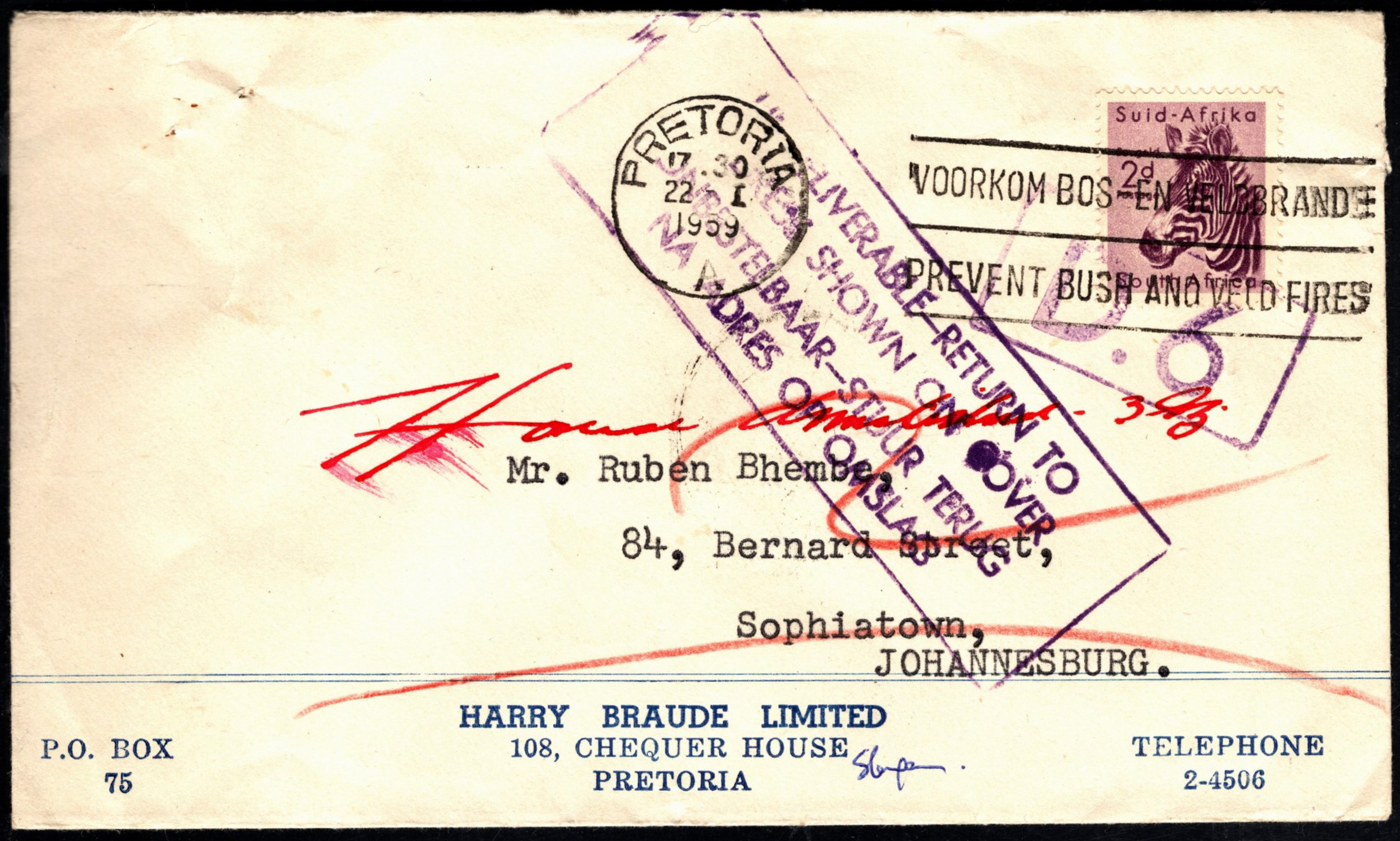

1959. Printed Cover. PRETORIA '22 I 59' 'PREVENT BUSH AND VELD FIRES' machine canceller to SOPHIATOWN.

Addressee and SOPHIATOWN deleted in red crayon. Marked 'HOUSE DEMOLISHED - ???' in red ink.

Stamped with purple rectangular cachet 'UNDELIVERABLE - RETURN TO ADDRESS SHOWN ON COVER'.

Also stamped with small boxed purple cachet 'D6', presumably associated with rectangular cachet.

Harry Braude Limited was a well-known Pretoria property management company ie. rent collector.Sophiatown's last remaining residents were forcibly evicted in 1955. The authorities immediately levelled it and began building a new White residential suburb. Only a few buildings, most notably the Anglican and Catholics churches, remained among Sophiatown's rubble. The evicted residents were moved to areas zoned for their specific racial group. Most Blacks were moved to Meadowlands, 13 miles outside of Johannesburg, The Coloured community was relocated to Eldorado Park, Westbury and Noordgesig. The Indians were moved to Lenasia. Curiously, some of the Chinese population was relocated to central Johannesburg, the rest to Marabastad, just west of the centre of Pretoria. (During the era of sanctions when Taiwan became an increasingly important trade partner (and sanction-buster) for South Africa, the Chinese community were accorded the status of 'Honorary Whites'.)

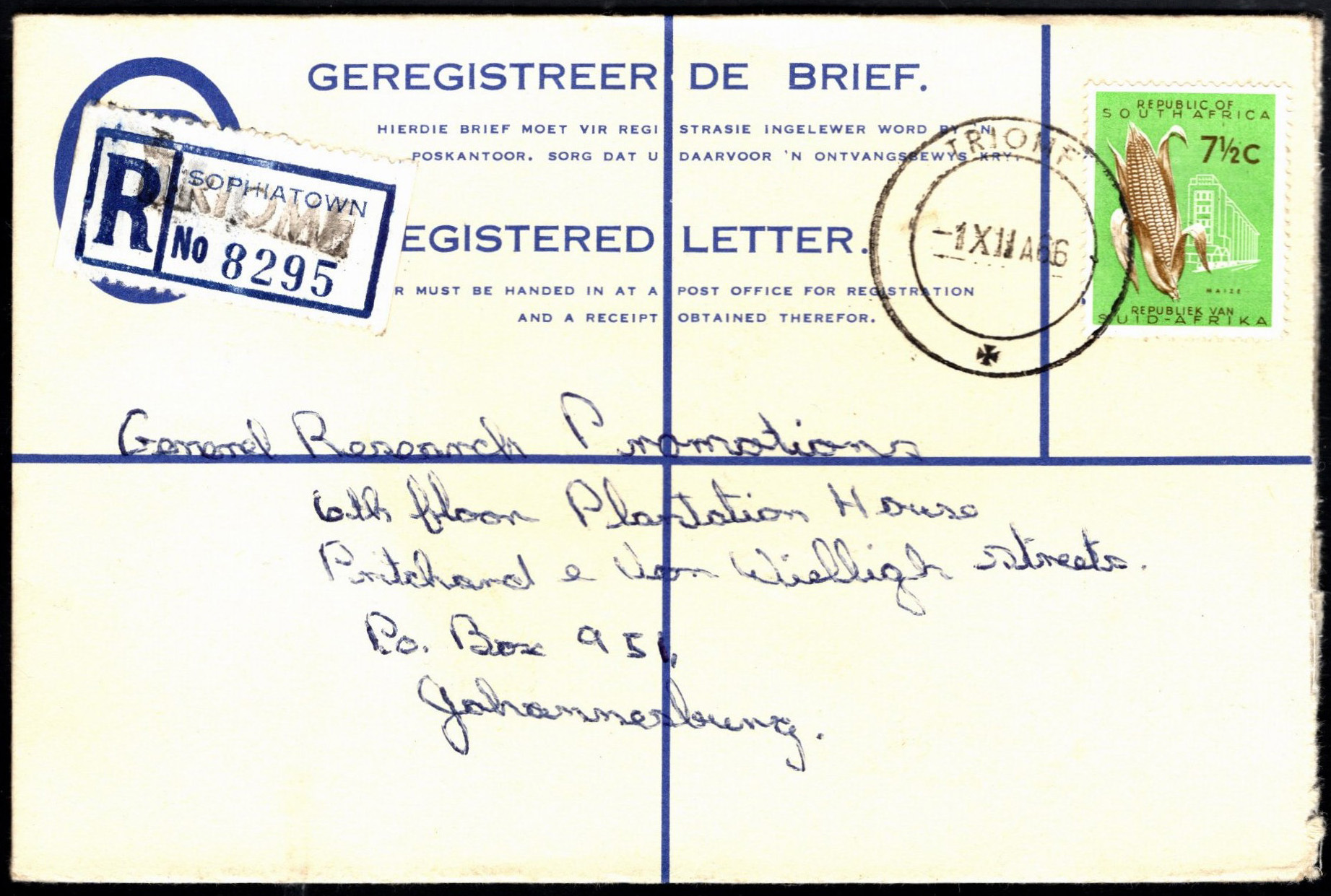

1966. Registered cover. TRIOMF D 31 XII 66' to Johannesburg.

The SOPHIATOWN registration label has been overstamped 'TRIOMF'.

(Display page courtesy of Bob Hill.)The area once known as Sophiatown was rebuilt as a spanking new residential suburb for White workers. In a delberately calculated act of propaganda and political resolve, the Nationalist government named the new White suburb 'Triomf', (Afr. Triumph). The Nats saw in their determined act of social engineering the triumph of Apartheid, something they had delivered which the previous more liberal Johannesburg Municipal authority had failed to achieve due to their political weaknesses. Triomf was the Nats 'Triumph of the Will'. With many leading Nats previously interned during WW2 for pro-Nazi sympathies, their choice of new town name was no coincidence.

Post-Apartheid Triomf was officially redesignated 'Sophiatown' in 2006. As far as is known, no postmarks have been recorded from this new Post Office. As ever, please add your comments and items below. Thanks.

Depending on who you talk to Sophiatown was either the most wonderful multi-cultural melting pot in Johannesburg or it was the city's 'vrot kol', (Afr. rotten spot), an area in desperate need of restoration and or rebuilding. The truth lies somewhere in-between. What is undeniable is that Sophiatown's most important contribution to South Africa's history was its destruction under Apartheid's Group Areas Act. This political act can be traced in the postal history covers below. They provide curious South Africans with good reasons to collect postal history as a hobby.

1941. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG. Putzel No. 2.

Putzel's 'The Postmarks of South Africa' list two Sophiatown Post Offices (1912 - 1915 and 1926 - 1966) using three different datestamps. The first, No. 1., the smallest at 25mm, says 'SOPHIATOWN' only with the Month in letters. Visser's Addendum lists a No. 1a 'date with block i.s.o. time code letter'. No's 2 and 3 are very similar to each other at 26mm, both saying 'SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG'. The difference lies in no. 3. having marginally larger text. Visser's Addendum lists a No. 2a 'date without time code letter'.

We start with a cover from the City of Johannesburg's Native Affairs Department who did not own the land on which Sophiatown was built. As a result, Sophiatown was not within the Native Affairs Department's remit. This prevented the City from taking drastic unilateral action against Sophiatown which it saw as a troublesome urban ghetto. Sophiatown would not survive after the Nationalists came to power in 1948 when they threw the entire weight of Apartheid legislation against Johannesburg's only inner-city Black suburb.

1932. Airmail cover. JOHANNESBURG '5 JUL 32' to GB.

1932. Airmail cover. JOHANNESBURG '5 JUL 32' to GB.

City of Johannesburg bilingual Native Affairs Department printed envelope.

The Native Affairs Department controlled the lives of Black South Africans in Municipal townships.

It did not own the land on which Sophiatown was built and as a consequence did not maintain it.

This was one of the reasons for Sophiatown's neglected state of disrepair.

(Cover courtesy of Bob Hill.)

Sophiatown was born of property speculation during Johannesburg's golden age. In 1897 Hermann Tobiansky purchased 237 acres of farmland some 4 miles west of the central Johannesburg for the purpose of creating a township. The South African War (1899 - 1902) put his plans on hold until 1903 when he had the private leasehold township surveyed and divided into almost 1700 small stands.

Tobiansky named the township after his wife, Sophia, and some of the main streets after his children. At this time, segregation existed but it was not yet set in political stone. Black South Africans still enjoyed freehold rights to owning property which they exercised within Sophiatown. The enactment of the Union's Natives Land Act, (1913) would remove this right. After the City of Johannesburg built a sewage plant nearby, wealthier property owners began to move out of Sophiatown. From 1920, its Black population increased due in large part to workers wanting to live closer to their places of employment in the City of Gold. Most rented the property they lived in.

1941. Registered letter. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG '20 VIII 41' to Westdene, Local.

This letter and the following one are philatelic in origin ie. created for postal history purposes.

Westdene was a White suburb adjoining Sophiatown. The addressee was presumably the sender also.

(Display page courtesy of Bob Hill.)

Although run-down, over-crowded and suffering poverty and crime, Sophiatown developed a metropolitan character that the Johannesburg City Council's abject Black township's lacked. Importantly, Black intelligentsia saw Sophiatown as a desirable place to live. It produced many South African Black writers, musicians, politicians and artists. Included among its inhabitants were colourful, street-wise 'tsotsis' (Sotho or Tswana. criminal). These criminals were romanticized in Black popular culture by Drum magazine.

One of its untruths was that Sophiatown's tsotsi underclass were noble criminals who stole only from Whites. The reality was that the tsotsi were a scourge on all who were vulnerable. In defining the new reality of African life in an urbanised, post-agricultural industrial society, Drum magazine searched for a new Black South African identity that rejected both its tribalism of the past and the White's policy of Apartheid that planned that they should perpetuate it in future tribal 'homelands'. The influence of American gangster movies in South Africa in the 1940s and 50s led Drum to find inspiration for the New South African Black Man in the Sophiatown 'tsotsi', an unwanted victim of segregation within White South Africa. Drum saw the tsotsi as an economic rebel stealing from the rich. Drum's tsotsi values would find a home among the rank and file of the ANC, South Africa's Black liberation movement, once in power.

1941. Registered letter. SOPHIATOWN JOHANNESBURG '31 IXI 41' to Westdene, Local.

This letter and the preceding one are philatelic in origin ie. created for postal history purposes.

Westdene was a White suburb adjoining Sophiatown. The addressee was presumably the sender also.

The Johannesburg City Council increasingly saw Sophiatown as a Black slum too close to White Johannesburg. As early as 1944 the City Council began planning to move the residents of Sophiatown out of Johannesburg. This met with resistance and made slow progress. However in 1948 the National Party won the post-war, Whites-only election on a promise of implementing the new racist policy of Apartheid as a means of securing the country for Europeans for the next 1000 years. Among its segregationist plans was the Group Areas Act, the Immorality Amendment Act, (both of 1950), and the Native Resettlement Act of 1954, all of which empowered the Nationalists to stop people of different races from living and or sleeping together. Each 'group' now had to live in areas zoned exclusively for them. Mixed residential areas were destroyed and replaced by zones of uniform urban racial segregation.

1959. Printed Cover. PRETORIA '22 I 59' 'PREVENT BUSH AND VELD FIRES' machine canceller to SOPHIATOWN.

Addressee and SOPHIATOWN deleted in red crayon. Marked 'HOUSE DEMOLISHED - ???' in red ink.

Stamped with purple rectangular cachet 'UNDELIVERABLE - RETURN TO ADDRESS SHOWN ON COVER'.

Also stamped with small boxed purple cachet 'D6', presumably associated with rectangular cachet.

Harry Braude Limited was a well-known Pretoria property management company ie. rent collector.

Sophiatown's last remaining residents were forcibly evicted in 1955. The authorities immediately levelled it and began building a new White residential suburb. Only a few buildings, most notably the Anglican and Catholics churches, remained among Sophiatown's rubble. The evicted residents were moved to areas zoned for their specific racial group. Most Blacks were moved to Meadowlands, 13 miles outside of Johannesburg, The Coloured community was relocated to Eldorado Park, Westbury and Noordgesig. The Indians were moved to Lenasia. Curiously, some of the Chinese population was relocated to central Johannesburg, the rest to Marabastad, just west of the centre of Pretoria. (During the era of sanctions when Taiwan became an increasingly important trade partner (and sanction-buster) for South Africa, the Chinese community were accorded the status of 'Honorary Whites'.)

1966. Registered cover. TRIOMF D 31 XII 66' to Johannesburg.

The SOPHIATOWN registration label has been overstamped 'TRIOMF'.

(Display page courtesy of Bob Hill.)

The area once known as Sophiatown was rebuilt as a spanking new residential suburb for White workers. In a delberately calculated act of propaganda and political resolve, the Nationalist government named the new White suburb 'Triomf', (Afr. Triumph). The Nats saw in their determined act of social engineering the triumph of Apartheid, something they had delivered which the previous more liberal Johannesburg Municipal authority had failed to achieve due to their political weaknesses. Triomf was the Nats 'Triumph of the Will'. With many leading Nats previously interned during WW2 for pro-Nazi sympathies, their choice of new town name was no coincidence.

Post-Apartheid Triomf was officially redesignated 'Sophiatown' in 2006. As far as is known, no postmarks have been recorded from this new Post Office. As ever, please add your comments and items below. Thanks.

Quote from Steve on August 7, 2025, 10:48 amI fear I was not strong enough in describing why Sophiatown was razed to the ground and rebuilt as the White suburb of Triomf. The single most compelling reason is that White segregationists did not want a Black residential area within central Johannesburg.

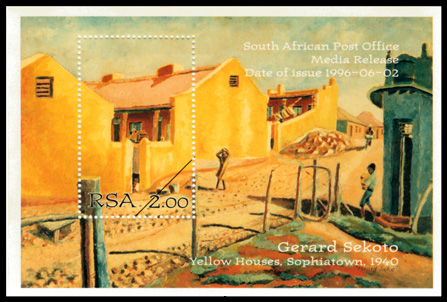

It has been suggested to me by someone who should know better that Sophiatown was a 'shanty town'. This suggests that it was unplanned and built willy-nilly with available ad hoc materials like corrugated iron, timber, recycled bricks and carboard. It was nothing of the sort. It was a properly surveyed, laid-out and built suburb much like any other suburb built for Whites in 1903 - 1910. As Sophiatown attracted more Black residents than Whites, most properties had annexes and outhouses built on or attached to them over time to accomodate the growing Black population's need for accomodation. This created a ramshackle appearance around what was a core of solid houses. See the painting 'Yellow Houses, Sophiatown 1949' by Gerard Sekoto below.

1996. 2 June. Miniature Sheet. 'Yellow Houses, Sophiatown', Gerard Sekoto, 1940.

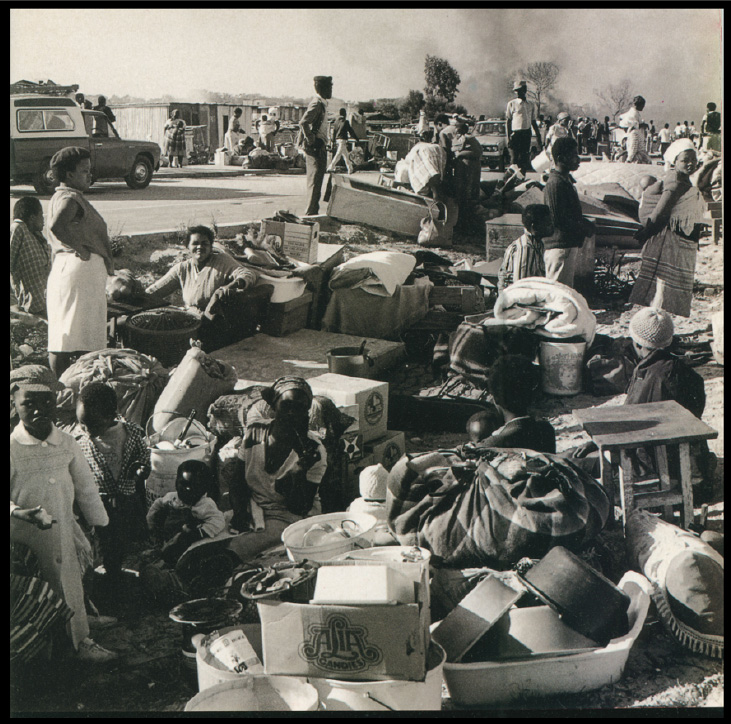

The awful events that took place in Sophiatown when the Nationalists forcibly evicted its residents were not unique to it. The image below shows a moment frozen in time from a similar enforced eviction in Cato Manor, Durban, Natal. Like Sophiatown, Cato Manor was a mixed residential area of Indians and Blacks close to Durban's city centre. District Six in central Cape Town suffered the same fate for the same reasons - White segrgationists did not want Blacks living in close proximty to areas like City Centres zoned for Whites. The removal of Coloured people to places like Bonteheuwel on the Cape Flats ripped the heart and soul out of Cape Town. I recall an American visitor to Cape Town saying that at night it was "like a third rate cemetery in New York with the lights turned off!"

Few on the Apartheid Government’s side have ever dared describe how they developed the bloody-minded, heartless indifference to human suffering needed to enforce Apartheid's Group Areas Act which had thousands of people thrown onto the streets in all sorts of weather while their homes were bull-dozed to the ground around them. Perhaps this heartlessness resulted from the sad fact that none of this was new. There were many times in the early 19th Century when Black people were burned out of their huts and had their land, cattle and children stolen by other tribes and left destitute to flee and starve in the veld. Ditto the Whites who came in search of farmland and who were in turn burned out by the Britsh Army during the South African War (1899 - 1902). It is not an excuse to do the same again.

Despite our rich history of holocaust and homeless horror, the reality of the Group Areas Act’s social engineering was more than many could bear to witness in what we thought post-WW2 was a more civilized age. Images like the above from Cato Manor in Durban in the 1960s added weight to the Western liberal charge that ‘White South Africa’ was a pariah nation to be boycotted.

I fear I was not strong enough in describing why Sophiatown was razed to the ground and rebuilt as the White suburb of Triomf. The single most compelling reason is that White segregationists did not want a Black residential area within central Johannesburg.

It has been suggested to me by someone who should know better that Sophiatown was a 'shanty town'. This suggests that it was unplanned and built willy-nilly with available ad hoc materials like corrugated iron, timber, recycled bricks and carboard. It was nothing of the sort. It was a properly surveyed, laid-out and built suburb much like any other suburb built for Whites in 1903 - 1910. As Sophiatown attracted more Black residents than Whites, most properties had annexes and outhouses built on or attached to them over time to accomodate the growing Black population's need for accomodation. This created a ramshackle appearance around what was a core of solid houses. See the painting 'Yellow Houses, Sophiatown 1949' by Gerard Sekoto below.

1996. 2 June. Miniature Sheet. 'Yellow Houses, Sophiatown', Gerard Sekoto, 1940.

The awful events that took place in Sophiatown when the Nationalists forcibly evicted its residents were not unique to it. The image below shows a moment frozen in time from a similar enforced eviction in Cato Manor, Durban, Natal. Like Sophiatown, Cato Manor was a mixed residential area of Indians and Blacks close to Durban's city centre. District Six in central Cape Town suffered the same fate for the same reasons - White segrgationists did not want Blacks living in close proximty to areas like City Centres zoned for Whites. The removal of Coloured people to places like Bonteheuwel on the Cape Flats ripped the heart and soul out of Cape Town. I recall an American visitor to Cape Town saying that at night it was "like a third rate cemetery in New York with the lights turned off!"

Few on the Apartheid Government’s side have ever dared describe how they developed the bloody-minded, heartless indifference to human suffering needed to enforce Apartheid's Group Areas Act which had thousands of people thrown onto the streets in all sorts of weather while their homes were bull-dozed to the ground around them. Perhaps this heartlessness resulted from the sad fact that none of this was new. There were many times in the early 19th Century when Black people were burned out of their huts and had their land, cattle and children stolen by other tribes and left destitute to flee and starve in the veld. Ditto the Whites who came in search of farmland and who were in turn burned out by the Britsh Army during the South African War (1899 - 1902). It is not an excuse to do the same again.

Despite our rich history of holocaust and homeless horror, the reality of the Group Areas Act’s social engineering was more than many could bear to witness in what we thought post-WW2 was a more civilized age. Images like the above from Cato Manor in Durban in the 1960s added weight to the Western liberal charge that ‘White South Africa’ was a pariah nation to be boycotted.

Quote from Steve on August 27, 2025, 3:02 pmAs stated above, Drum magazine romanticised the tsotsis (gangsters) of Sophiatown. It was a desperate time. Apartheid seemed fixed in stone, categorising people by race and races by tribe. There seemed to few charismatic heroes in the Black community capable of standing up to the Apartheid regime and the SAP (South African Police) who implemented its race laws, often with cruel relish.

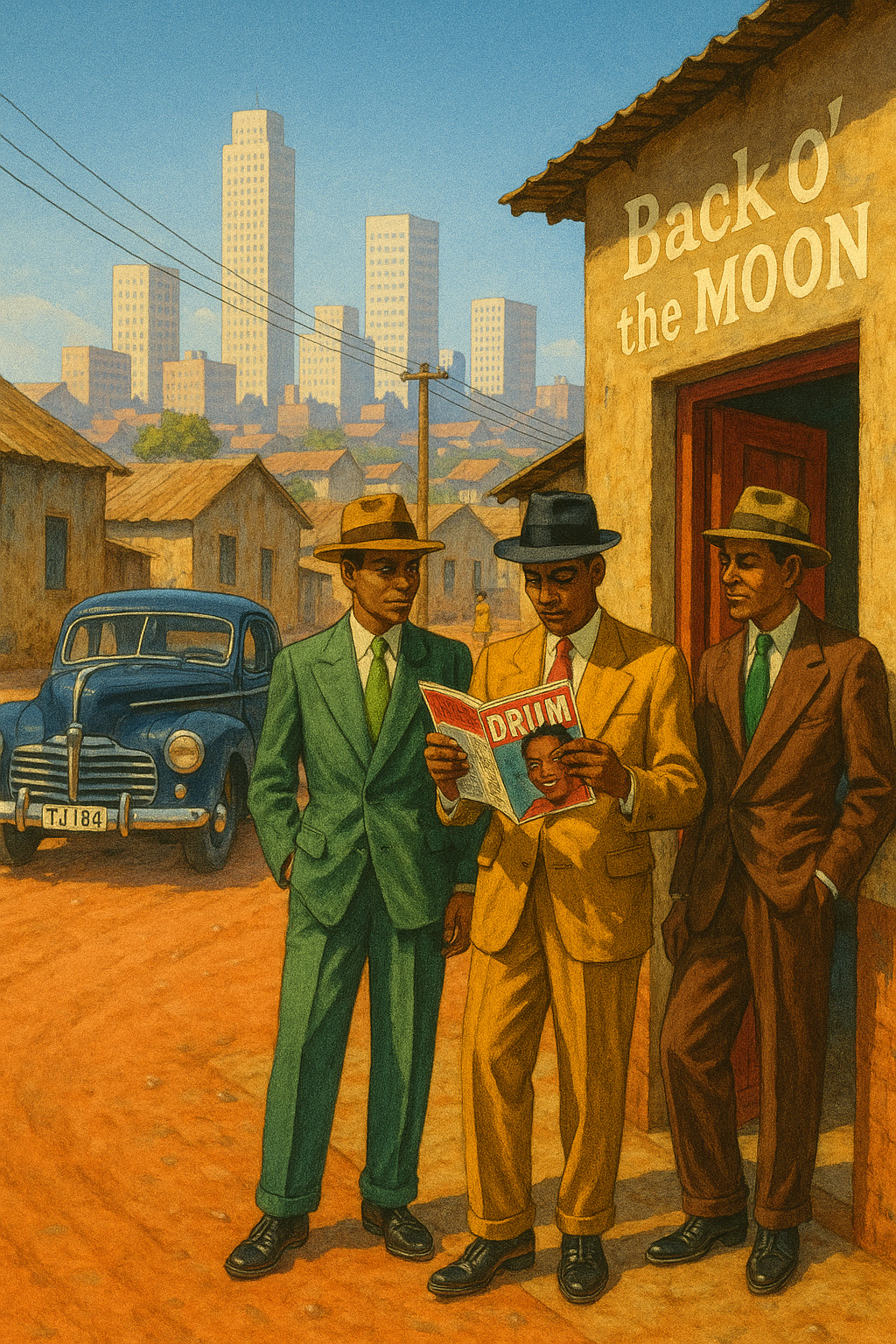

ChatGPT AI image. "What is Drum saying about us today?"

Johannesburg tsotis hang out at Sophiatown's Back o' the Moon shebeen in the 1950s.

They are well-dressed, have an American car and shoes. Importantly, they have money, respect and publicity.Many of the Black intelligentstia lived in Sophiatown, some writing for Drum magazine. It idealised the cheerful, cheeky tsotsi criminals and made much of their claim to steal only from Whites. These Robbin' Hoods became a role model of a sort for the new South African metropolitan Black man, one who could get rich quick only by breaking the law and stealing from the wealthy Whites. Drum magazine made the case that the proud tsotsi represented a form of Black liberation and the redistribution of White wealth by other means.

This colourful narrative was readily acceptable to the Black majority and also to liberal Whites. In Cape Town in the 1970s I met an old jailbird, a scarred and tattoed Coloured 'joster', Cape slang for gangster, He proudly proclaimed "I am an honest gangster. I only robbed Whites, not my own people, not like this rubbish today." This was in part Drum's influence. The magazine's argument about the nobility of tsotsi crime made its way into mainstream of Black politics and White liberal guilt. With anti-Apartheid politics based around a core central tenet that it was wrong for Whites to have it all to themselves, there was a recognition of the need for the redistribution of wealth by fair means and foul. Today's corrupt criminal activties by members of the ANC government is in part the consequence of Drum confusing criminal behaviour with heroism, political resistance and some sort of retributive justice against Whites and the State.

Whatever the truth, ANC corruption today has made all South Africans poorer. The ANC feels no guilt or shame in what its members have done to enrich themselves. Few have paid their ill-gotten gains back, apologised or been caught and sentenced. It's okay if you can get away with it. Just don't get caught. Its a sad fact that theft remains the only way many unemployed Black South Africans can advance financially today. The tragic reality, however, is that ANC corruption takes place not in a dark back alley in downtown eGoli but in the well-lit corridors of power, a place the poor cannot access despite politicians promising that they are working on their behalf. A lot and very little has changed since the final days of Sophiatown when its oppressed hoped for a bright and prosperous democratic future.

As stated above, Drum magazine romanticised the tsotsis (gangsters) of Sophiatown. It was a desperate time. Apartheid seemed fixed in stone, categorising people by race and races by tribe. There seemed to few charismatic heroes in the Black community capable of standing up to the Apartheid regime and the SAP (South African Police) who implemented its race laws, often with cruel relish.

ChatGPT AI image. "What is Drum saying about us today?"

Johannesburg tsotis hang out at Sophiatown's Back o' the Moon shebeen in the 1950s.

They are well-dressed, have an American car and shoes. Importantly, they have money, respect and publicity.

Many of the Black intelligentstia lived in Sophiatown, some writing for Drum magazine. It idealised the cheerful, cheeky tsotsi criminals and made much of their claim to steal only from Whites. These Robbin' Hoods became a role model of a sort for the new South African metropolitan Black man, one who could get rich quick only by breaking the law and stealing from the wealthy Whites. Drum magazine made the case that the proud tsotsi represented a form of Black liberation and the redistribution of White wealth by other means.

This colourful narrative was readily acceptable to the Black majority and also to liberal Whites. In Cape Town in the 1970s I met an old jailbird, a scarred and tattoed Coloured 'joster', Cape slang for gangster, He proudly proclaimed "I am an honest gangster. I only robbed Whites, not my own people, not like this rubbish today." This was in part Drum's influence. The magazine's argument about the nobility of tsotsi crime made its way into mainstream of Black politics and White liberal guilt. With anti-Apartheid politics based around a core central tenet that it was wrong for Whites to have it all to themselves, there was a recognition of the need for the redistribution of wealth by fair means and foul. Today's corrupt criminal activties by members of the ANC government is in part the consequence of Drum confusing criminal behaviour with heroism, political resistance and some sort of retributive justice against Whites and the State.

Whatever the truth, ANC corruption today has made all South Africans poorer. The ANC feels no guilt or shame in what its members have done to enrich themselves. Few have paid their ill-gotten gains back, apologised or been caught and sentenced. It's okay if you can get away with it. Just don't get caught. Its a sad fact that theft remains the only way many unemployed Black South Africans can advance financially today. The tragic reality, however, is that ANC corruption takes place not in a dark back alley in downtown eGoli but in the well-lit corridors of power, a place the poor cannot access despite politicians promising that they are working on their behalf. A lot and very little has changed since the final days of Sophiatown when its oppressed hoped for a bright and prosperous democratic future.

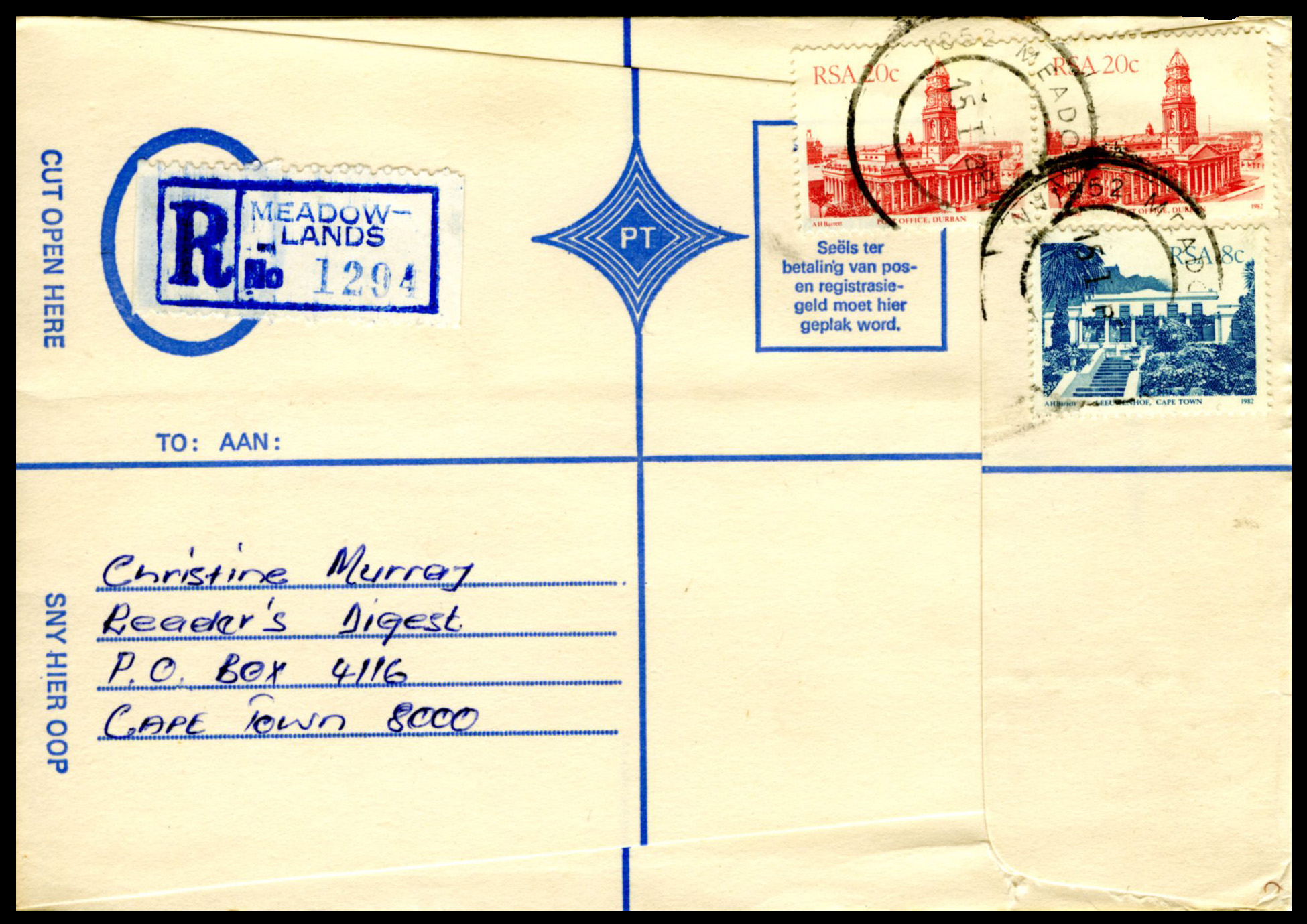

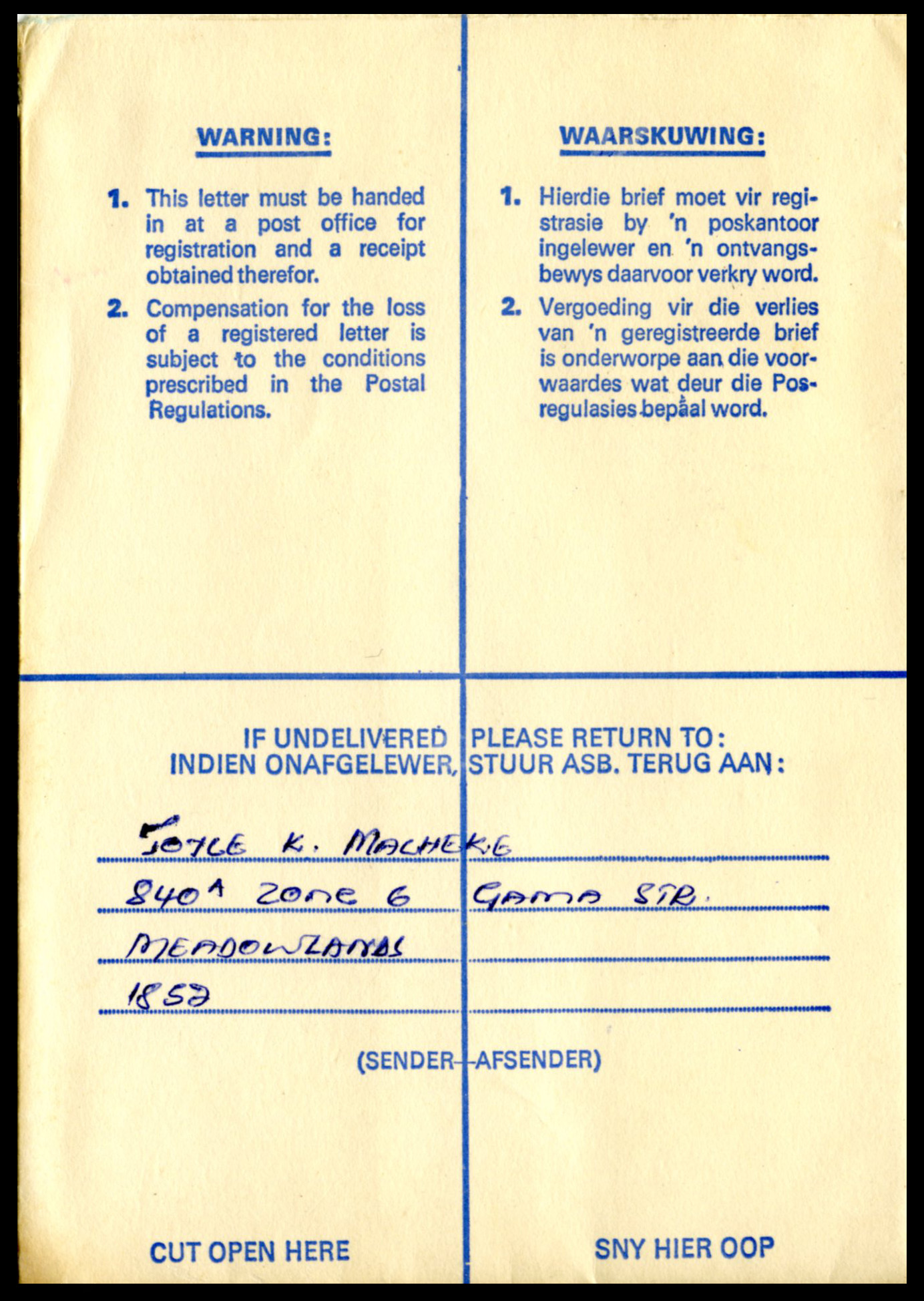

Quote from Steve on September 15, 2025, 4:39 pmThe Black residents of Sophiatown were in the most part relocated to Meadowlands township, part of the sprawling Soweto (South Western Townships) complex that provided workers to the Rand industrial area. Bob Hill has sent the following Registered letter from Meadowlands to more-or-less complete the unhappy postal history of the average Sophiatown resident.

1983. Registered letter stationery front. MEADOWLANDS '15 I 83' to CAPE TOWN.

1983. Registered letter stationery reverse. MEADOWLANDS '15 I 83' to CAPE TOWN.

The Black residents of Sophiatown were in the most part relocated to Meadowlands township, part of the sprawling Soweto (South Western Townships) complex that provided workers to the Rand industrial area. Bob Hill has sent the following Registered letter from Meadowlands to more-or-less complete the unhappy postal history of the average Sophiatown resident.

1983. Registered letter stationery front. MEADOWLANDS '15 I 83' to CAPE TOWN.

1983. Registered letter stationery reverse. MEADOWLANDS '15 I 83' to CAPE TOWN.