The Dutch apologise for Slavery

Quote from Steve on December 24, 2022, 2:57 pmThe big political / postal history news that comes at the end of 2022 is the apology by the Dutch Government "for the Netherlands’ role in the history of slavery". (Ministry of General Affairs, Government of the Netherlands, 19-12-2022). As most postal history collectors will know, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) practised slavery for all but the first six years of its time at the Cape. The reality though is that the influence of the Dutch in South Africa is much broader, longer and more insidious than the narrow time-line of VOC slavery (1658 -1795) suggests.

A few days ago the Dutch government issued a press release which stated: "In a speech this afternoon, Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologised for the past actions of the Dutch State: to enslaved people in the past, everywhere in the world, who suffered as a consequence of those actions, as well as to their daughters and sons, and to all their descendants, up to the present day". While an apology is always welcome, any reparations which the descendants of slaves surely hope for is likely to be contested. This will, no doubt, be the subject of heated and virtuous debate.

Rutte gave the apology at the National Archives in The Hague, in the presence of representatives of organisations that have pressed for acknowledgement of the effects of slavery ie. ongoing injustices. In Suriname and on Aruba, Curaçao, St Maarten, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba, members of the government will meet with organisations and authorities to discuss what this apology means in each of those places. It suggests that the islands of the Dutch Antilles are expecting substantial restitutional payments to counter the effects of slavery.

The press release does not specifically include the Cape, now a part of the Republic of South Africa. The issue of slavery at the Cape of Good Hope is complicated and is not covered in depth here. As far as I know, slaves at the Cape were exclusively Black people. This stigmatisation of one race as slave-worthy and another as slave-owning allowed racial discrimination in South Africa to flourish. It created a mindset of racial inferiority and superiority with the consequent need for segregation of the two. The mindset of slavery made Apartheid acceptable. Do the Dutch share a responsibility for Apartheid? Its architect, Dr Verwoerd, was born in Holland in 1901.

Rutte admits that the VOC received a wide-ranging Charter from the Dutch government, one that allowed it to start colonies, execute people, mint coin and trade in slaves. This allowed the VOC to start a replenishment station at the Cape in 1652 without the express agreement of the people (Khoikhoi) living there. The Khoi were reluctant to assist VOC settlement and witheld the sale of livestock and the provision of labour to the Dutch. This forced the VOC to make some of its indentured servants free burgher farmers (Boers) in 1657. This was the start of Dutch colonisation of native Khoi land. In 1658 the VOC began to import slaves to do menial labouring work.

Over time, the Khoi were defeated in war and or destroyed by smallpox from 1713 on. Dispossessed of their land and livestock, the survivors ended up in servitude and or bondage. The Boer farming community trekked into the interior to occupy the lost lands of the Khoi which the VOC now sold to them. As most Boers were too poor to own slaves they made more use of Khoi servants. Slaves were sold in Church Square in full view of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town which stood alongside the Slave Lodge, built in 1679. From 1720 there would always be more slaves at the Cape than European settlers. The majority of all slaves were owned by some 60 families on large Western Cape estates. There were far fewer slaves on the distant frontier, most trek boers being too poor to afford them. The moral question of slavery as an institutionalised economic system was not a burning political issue among European slave-owners at the Cape. Far more troubling for them was the prosperct of slave revolts. As a result, the iniquitous slave-owning status quo was enforced with great cruelty and ruthlessness, as was slavery protected everywhere it was practised. European visitors were horrified by what they saw.

Slavery was an economic system in which the owner made a one-time payment for the cost of labour. After the British occupied the Cape in 1806, Britainy acquired the slaves previously owned by the VOC. Some were sold while others were kept until freed. In 1807 Britain's Slave Trade Act prohbited further trade in slaves. However, as the economy of the Cape was based on slavery, the ownership of slaves was allowed to continue. The argument ran that an economy based on an institution that had been 148 years in the making could not be done away with overnight without severe financial upheaval and cost. Expensive reparations would need to be made to slave owners. When Britain finally emancipated Cape slaves in 1834, they numbered some 35,000 and made up about 55% of Cape Town's population.

The cost of emanicipation brought unexpected consequences. With most British slave-owners living in the UK , Britain ruled that remuneration for freed slaves would only to be paid out in London. This made it very difficult for all but the wealthiest Cape slave owners to claim for the loss of their emancipated slaves. The majority of Boers did not own enough slaves and lived too precariously to warrant the time and cost of a long overseas trip to London and back. As a result, slave-owning Boers felt cheated by Britain. This grievance certainly contributed to the decision by some Boers to join the Great Trek in order to escape perfidious Albion and establish a country of their own in the interior of South Africa. In this regard, both the Dutch who introduced slaves and the British who cheated Boers from remunerations for them bear some responsibility for the consequences of subsequent actions in areas soon to be occupied by Boers.

With the Khoi reduced to serfdom on the margins of land they once owned, many of the Khoi survivors in the Western Cape merged with the descendants of slaves to create the so-called 'Cape Coloured' community, a vibrant mixed-race group that the narrow race-dividing categories of Apartheid had great difficulty in accomodating, both racially and culturally, being neither black nor white . Whatever the rights and wrongs of the Khoi's resistance and the Boers' acquisition of their land, many within the 'Cape Coloured' community carry a wearisome double grievance towards the history of the Dutch in South Africa, a dual legacy of lost land and slavery.

It is right that the Dutch should have a profound sense of historic involvement slavery worldwide and in the evolution of South Africa. It will be interesting to see what comes of this.

Images (Top to Bottom).

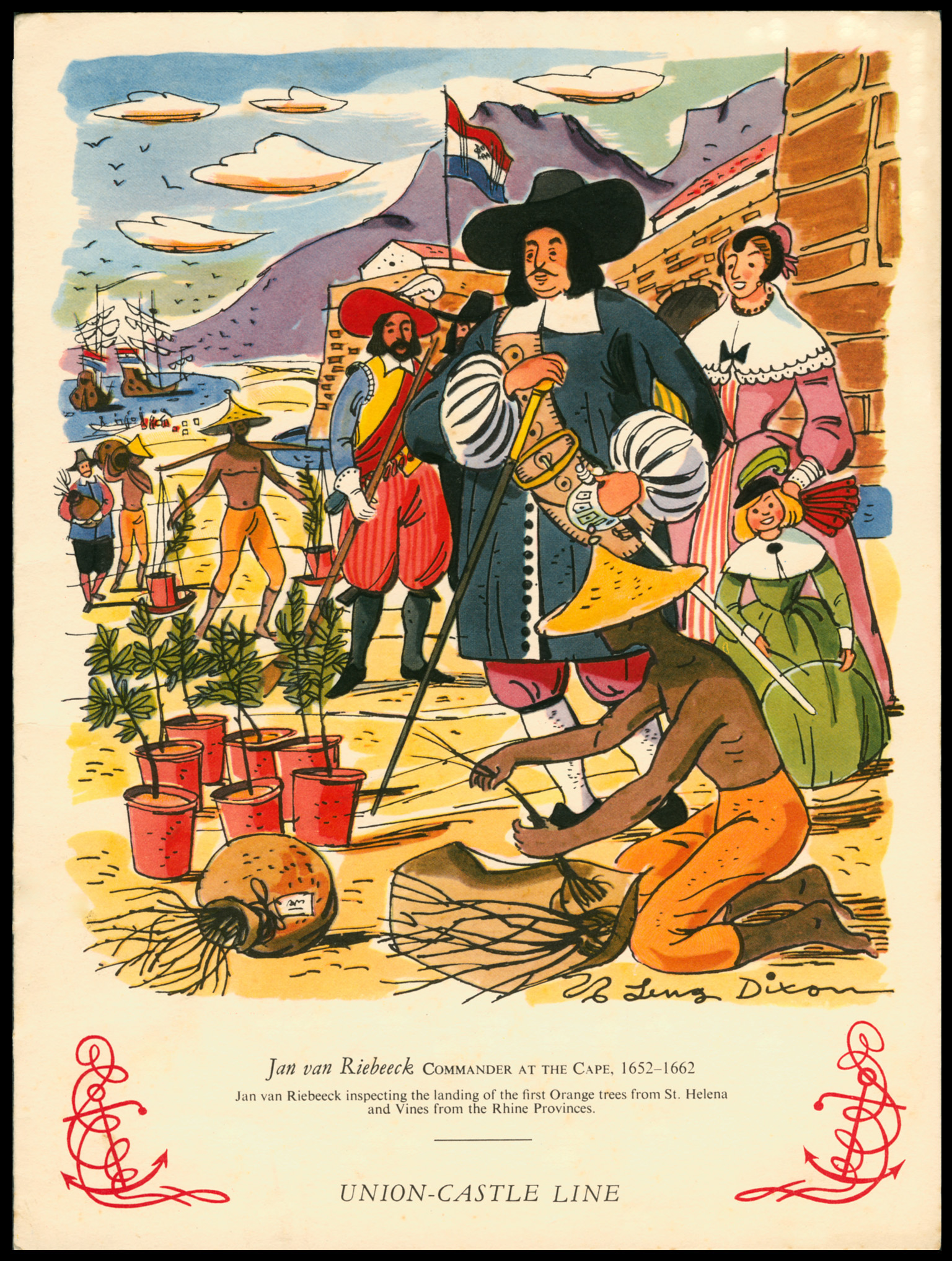

1]. Union-Castle Line schmaltz, wonderfully illustrated but a romanticised nonsense showing the gracious Dutch Commander and his family at the Cape inspecting the labour of Asian slaves. From the outset, Commander Jan van Riebeeck agitated for the importation of slaves to overcome the labour shortage. The stone Castle is historically wrong for this time - it was a sod and timber fort - but the corpulent van Riebeeck appears to be the 'right' man. (See next).

2]. SA Reserve Bank Fiver showing Batholomeus Vermuyden, the 'wrong' van Riebeeck. It is somewhat fitting that the myth of White South Africa should be based on the mistaken identity of its founding father. In the note we see a White Hope watching Boers moving out to occupy the land of the Khoi. A wonderful tribute to the engraver's skills, this image is little but sentimental propaganda.

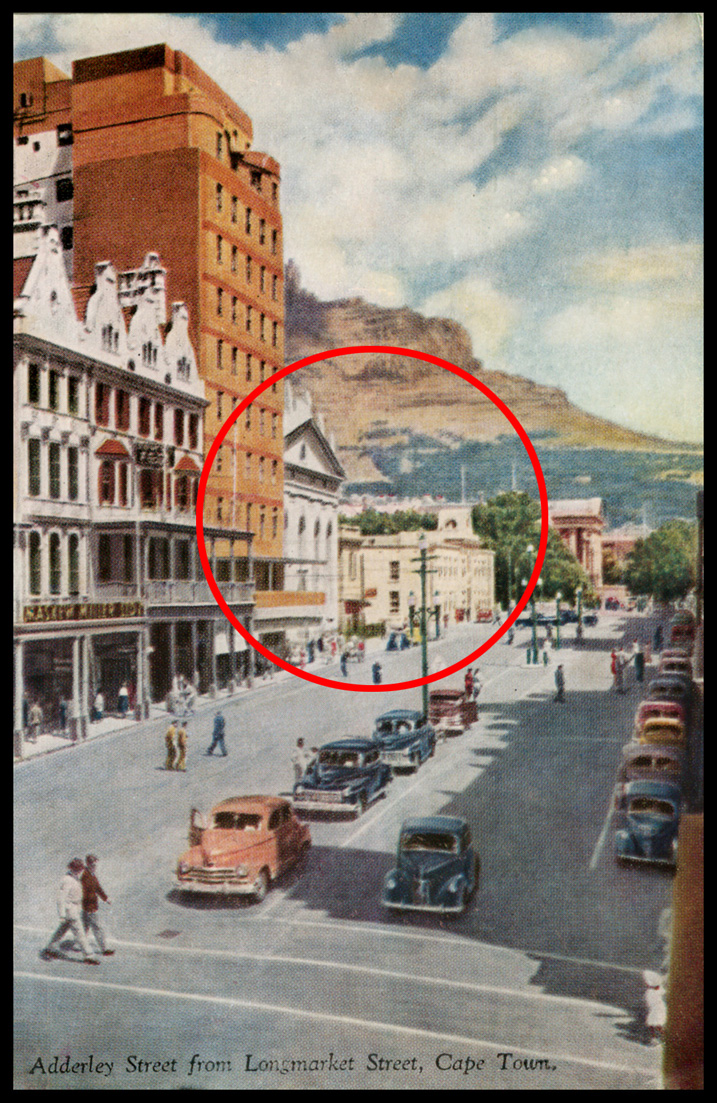

3]. Highlighted view of the Groote Kerk standing alongside the old Slave Lodge at the top of Adderley street. This cosy working relationship lasted 148 years. It explains much about the Dutch Reformed Church's long-standing support for Apartheid and it and its flock's failure with a few notable exceptions to challenge the prevailing racist status quo.

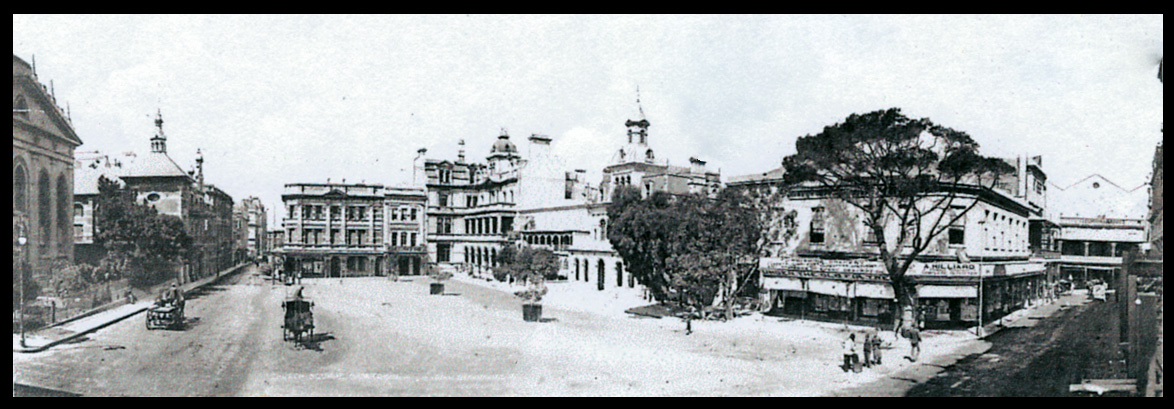

4]. Church Square, Cape Town. The photographer is standing with his back to the old Slave Lodge. The Groote Kerk is on the left opening onto Parliament Street and the Square. The Old Slave Tree is the one on the right. It was under this tree, within sound and sight of the Church, that slaves were sold. The proximity of the church to the slave lodge says much about Calvinist Christianity and the development of segregation as a way of life. After the British renovated, the old Slave Lodge it would house the first post office outside the Castle in 1809. Our thanks to Bob Hill for supplying this image, the same one Ralph Putzel uses in his Encyclopedia.

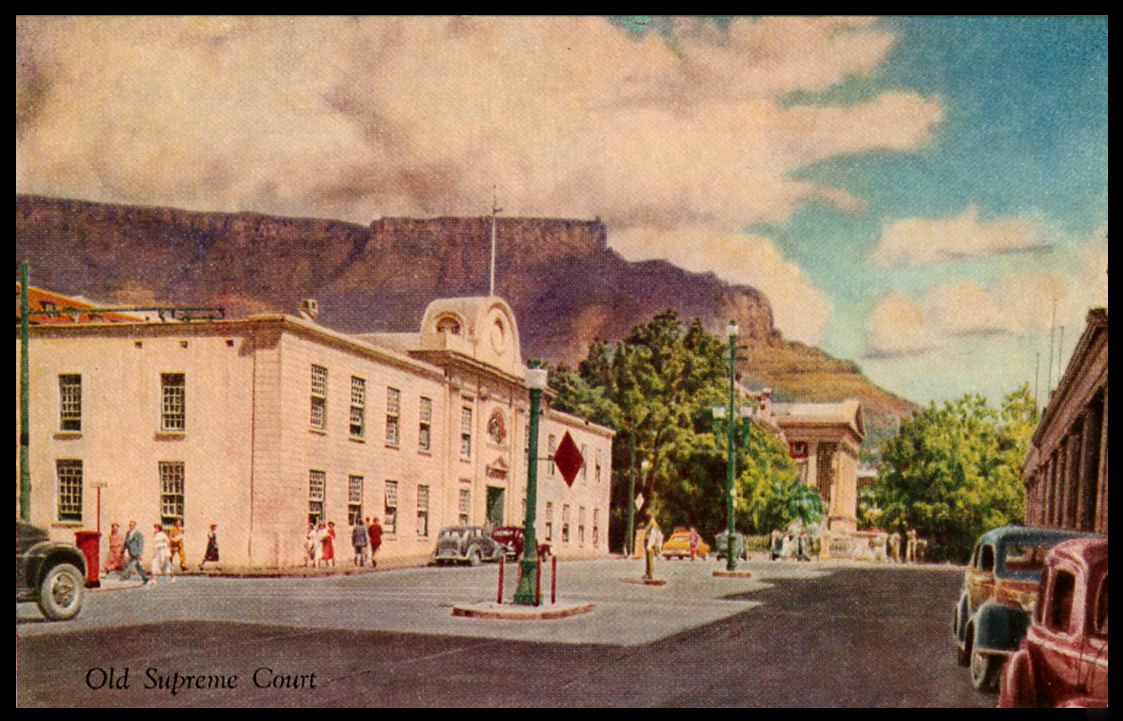

5]. The Old Supreme Court, previously the Slave Lodge. From 1679 to about 1807 it housed VOC slaves who laboured in Cape Town and in the Company Gardens that lay behind the trees. In 1809 South Africa's first post office was based in one of two different offices in the renovated Slave Lodge. It is believed the last post office was in the building's nearest corner opposite the red post box left. Robert Crozier, the Postmaster General, owned slaves. Previously the Apartheid-era Cultural History Museum, it is today the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum.

The big political / postal history news that comes at the end of 2022 is the apology by the Dutch Government "for the Netherlands’ role in the history of slavery". (Ministry of General Affairs, Government of the Netherlands, 19-12-2022). As most postal history collectors will know, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) practised slavery for all but the first six years of its time at the Cape. The reality though is that the influence of the Dutch in South Africa is much broader, longer and more insidious than the narrow time-line of VOC slavery (1658 -1795) suggests.

A few days ago the Dutch government issued a press release which stated: "In a speech this afternoon, Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologised for the past actions of the Dutch State: to enslaved people in the past, everywhere in the world, who suffered as a consequence of those actions, as well as to their daughters and sons, and to all their descendants, up to the present day". While an apology is always welcome, any reparations which the descendants of slaves surely hope for is likely to be contested. This will, no doubt, be the subject of heated and virtuous debate.

Rutte gave the apology at the National Archives in The Hague, in the presence of representatives of organisations that have pressed for acknowledgement of the effects of slavery ie. ongoing injustices. In Suriname and on Aruba, Curaçao, St Maarten, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba, members of the government will meet with organisations and authorities to discuss what this apology means in each of those places. It suggests that the islands of the Dutch Antilles are expecting substantial restitutional payments to counter the effects of slavery.

The press release does not specifically include the Cape, now a part of the Republic of South Africa. The issue of slavery at the Cape of Good Hope is complicated and is not covered in depth here. As far as I know, slaves at the Cape were exclusively Black people. This stigmatisation of one race as slave-worthy and another as slave-owning allowed racial discrimination in South Africa to flourish. It created a mindset of racial inferiority and superiority with the consequent need for segregation of the two. The mindset of slavery made Apartheid acceptable. Do the Dutch share a responsibility for Apartheid? Its architect, Dr Verwoerd, was born in Holland in 1901.

Rutte admits that the VOC received a wide-ranging Charter from the Dutch government, one that allowed it to start colonies, execute people, mint coin and trade in slaves. This allowed the VOC to start a replenishment station at the Cape in 1652 without the express agreement of the people (Khoikhoi) living there. The Khoi were reluctant to assist VOC settlement and witheld the sale of livestock and the provision of labour to the Dutch. This forced the VOC to make some of its indentured servants free burgher farmers (Boers) in 1657. This was the start of Dutch colonisation of native Khoi land. In 1658 the VOC began to import slaves to do menial labouring work.

Over time, the Khoi were defeated in war and or destroyed by smallpox from 1713 on. Dispossessed of their land and livestock, the survivors ended up in servitude and or bondage. The Boer farming community trekked into the interior to occupy the lost lands of the Khoi which the VOC now sold to them. As most Boers were too poor to own slaves they made more use of Khoi servants. Slaves were sold in Church Square in full view of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town which stood alongside the Slave Lodge, built in 1679. From 1720 there would always be more slaves at the Cape than European settlers. The majority of all slaves were owned by some 60 families on large Western Cape estates. There were far fewer slaves on the distant frontier, most trek boers being too poor to afford them. The moral question of slavery as an institutionalised economic system was not a burning political issue among European slave-owners at the Cape. Far more troubling for them was the prosperct of slave revolts. As a result, the iniquitous slave-owning status quo was enforced with great cruelty and ruthlessness, as was slavery protected everywhere it was practised. European visitors were horrified by what they saw.

Slavery was an economic system in which the owner made a one-time payment for the cost of labour. After the British occupied the Cape in 1806, Britainy acquired the slaves previously owned by the VOC. Some were sold while others were kept until freed. In 1807 Britain's Slave Trade Act prohbited further trade in slaves. However, as the economy of the Cape was based on slavery, the ownership of slaves was allowed to continue. The argument ran that an economy based on an institution that had been 148 years in the making could not be done away with overnight without severe financial upheaval and cost. Expensive reparations would need to be made to slave owners. When Britain finally emancipated Cape slaves in 1834, they numbered some 35,000 and made up about 55% of Cape Town's population.

The cost of emanicipation brought unexpected consequences. With most British slave-owners living in the UK , Britain ruled that remuneration for freed slaves would only to be paid out in London. This made it very difficult for all but the wealthiest Cape slave owners to claim for the loss of their emancipated slaves. The majority of Boers did not own enough slaves and lived too precariously to warrant the time and cost of a long overseas trip to London and back. As a result, slave-owning Boers felt cheated by Britain. This grievance certainly contributed to the decision by some Boers to join the Great Trek in order to escape perfidious Albion and establish a country of their own in the interior of South Africa. In this regard, both the Dutch who introduced slaves and the British who cheated Boers from remunerations for them bear some responsibility for the consequences of subsequent actions in areas soon to be occupied by Boers.

With the Khoi reduced to serfdom on the margins of land they once owned, many of the Khoi survivors in the Western Cape merged with the descendants of slaves to create the so-called 'Cape Coloured' community, a vibrant mixed-race group that the narrow race-dividing categories of Apartheid had great difficulty in accomodating, both racially and culturally, being neither black nor white . Whatever the rights and wrongs of the Khoi's resistance and the Boers' acquisition of their land, many within the 'Cape Coloured' community carry a wearisome double grievance towards the history of the Dutch in South Africa, a dual legacy of lost land and slavery.

It is right that the Dutch should have a profound sense of historic involvement slavery worldwide and in the evolution of South Africa. It will be interesting to see what comes of this.

Images (Top to Bottom).

1]. Union-Castle Line schmaltz, wonderfully illustrated but a romanticised nonsense showing the gracious Dutch Commander and his family at the Cape inspecting the labour of Asian slaves. From the outset, Commander Jan van Riebeeck agitated for the importation of slaves to overcome the labour shortage. The stone Castle is historically wrong for this time - it was a sod and timber fort - but the corpulent van Riebeeck appears to be the 'right' man. (See next).

2]. SA Reserve Bank Fiver showing Batholomeus Vermuyden, the 'wrong' van Riebeeck. It is somewhat fitting that the myth of White South Africa should be based on the mistaken identity of its founding father. In the note we see a White Hope watching Boers moving out to occupy the land of the Khoi. A wonderful tribute to the engraver's skills, this image is little but sentimental propaganda.

3]. Highlighted view of the Groote Kerk standing alongside the old Slave Lodge at the top of Adderley street. This cosy working relationship lasted 148 years. It explains much about the Dutch Reformed Church's long-standing support for Apartheid and it and its flock's failure with a few notable exceptions to challenge the prevailing racist status quo.

4]. Church Square, Cape Town. The photographer is standing with his back to the old Slave Lodge. The Groote Kerk is on the left opening onto Parliament Street and the Square. The Old Slave Tree is the one on the right. It was under this tree, within sound and sight of the Church, that slaves were sold. The proximity of the church to the slave lodge says much about Calvinist Christianity and the development of segregation as a way of life. After the British renovated, the old Slave Lodge it would house the first post office outside the Castle in 1809. Our thanks to Bob Hill for supplying this image, the same one Ralph Putzel uses in his Encyclopedia.

5]. The Old Supreme Court, previously the Slave Lodge. From 1679 to about 1807 it housed VOC slaves who laboured in Cape Town and in the Company Gardens that lay behind the trees. In 1809 South Africa's first post office was based in one of two different offices in the renovated Slave Lodge. It is believed the last post office was in the building's nearest corner opposite the red post box left. Robert Crozier, the Postmaster General, owned slaves. Previously the Apartheid-era Cultural History Museum, it is today the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum.

Uploaded files:Quote from Steve on December 25, 2022, 1:45 pm"So what? It was a long time ago and has nothing to do with us today. What's this got to do with philately?".

Having been given a wide-ranging charter by the Dutch government, including the 'right' to trade in slaves, the VOC contributed greatly to the 'Golden Age of Holland' which peaked at about the time van Riebeeck landed at the Cape. The wealth of Holland and Britain today is based to some extent on the misery it inflicted on people - slaves and others - who toiled to exploit profits from their hell-hole colonial adventures.

Following decades of declining profits the VOC was liquidated in 1800. (Its slow financial failure contributed to the difficulties of starting a post office at the Cape in 1792.) The VOC's assets (including slaves) and liabilities accrued to the Batavian Republic ie. the government of Holland. The slave trade continued under the Batavian Republic at the Cape until it was occupied by the British for the second time in 1806. The British ended the slave trade but not slavery at the Cape in 1807. Responsibility for the VOC slave trade lay with the Dutch government who gave them their charter. It is only right that they recognise this was wrong.

Both slavery and stamps were a product of government. The post office is an arm of government subject to the rules of law. Lest you forget, in South Africa the post office was segregated. Those of us who collect stamps or covers are only able to do so because the post office as a warts-and-all arm of government made it possible. The politics of the day, imperial, nationalist, communist, fascist or other are expressed through stamps and covers. Today, many people deride the 'boring' hobby of stamp collecting as something grandpa did. Whatever stamp collecting's detractors have to say about 'the hobby of kings and presidents', many will acknowledge the greater validity and importance of collecting historical items of mail, some of which were posted by trusted slaves in the post office in the Castle, Cape Town, and later in the renovated Slave Lodge until 1834. South Africa's earliest mail has a direct line to slavery via the politics of the day, politics that over time embraced institutional discrimination, segregation and full-blown Apartheid.

Images

1]. Cinderella labels from the Seventh Philatelic Congress of SA, Cape Town, 1938, showing the 6 stuiwe handstamp with the VOC logo and a Cape 'woodblock'. A. A. Jurgens RDPSA FRPSL had a hand in this design.

2]. The 1952 Tercentennary set on stamps! The Dutch commander who repeatedly asked for slaves, the 'father of White South Africa', the 'wrong' Jan van Riebeeck, his vrou, his three ships arriving, his seal of authority and Charles Bell's 'Landing of the Dutch at the Cape', all are nothing less than propaganda pieces for the myth of White South Africa and a Nationalist government hell-bent on implementing Apartheid.

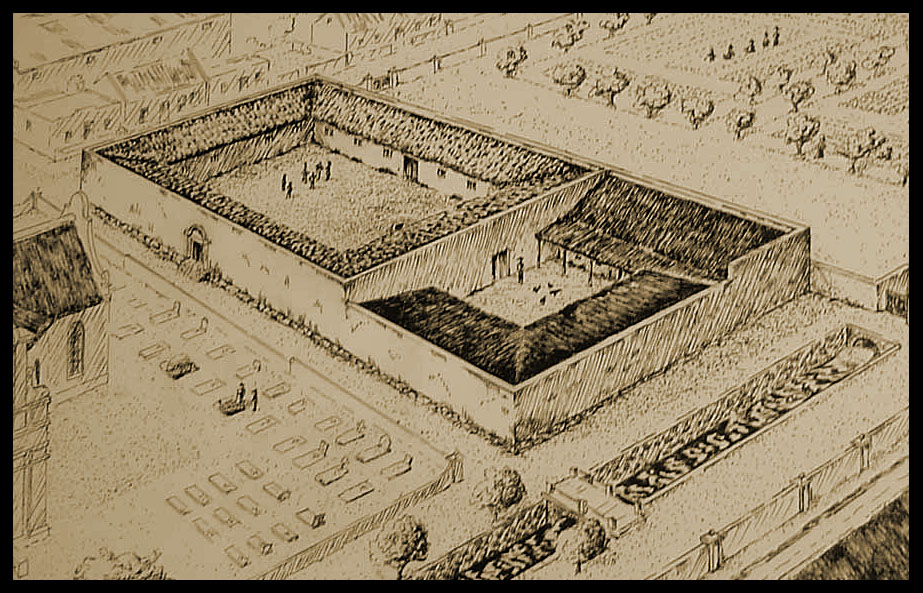

3]. An early sketch of the Slave Lodge built in 1679 to house Cape Town's slaves. In 1658 van Riebeeck received the first large 'consignment' (as in traded 'goods') of slaves. They were housed in and outside the original fort. As this was an impractical long-term arrrangement for housing the rapidly increasing slave population, a 'slave lodge' was built in 1679 alongside the first church of Christian worship in SA at the foot of the Company Gardens. The close proximity between fundamentalist Christianity worship and the practice of slavery saw racial discrimination develop as a way of life in CapeTown. The footbridge centre right spans a drainage ditch, the Heerengracht, (Dutch. the Gentleman's, Lord's or Patrician's Canal).

4]. Weenen Massacre. After the collapse of Khoi culture in the Western Cape, many of the surviving Khoi became 'servants'of the Boers. This wonderfully dramatic painting by Charles Bell no longer enjoys official approval. Here we see Khoi servants fighting alongside their Boer Voortrekker masters against the Zulu in Natal. According to the character of Adendorff, (Gert van den Bergh), in the 1964 movie 'Zulu', the treacherous murder of Boer trekkers established a blood feud between Boer and Zulu. Sadly, the loyalty of the Khoi and other Black servants shown here was never rewarded by the Boers who quickly discarded them.

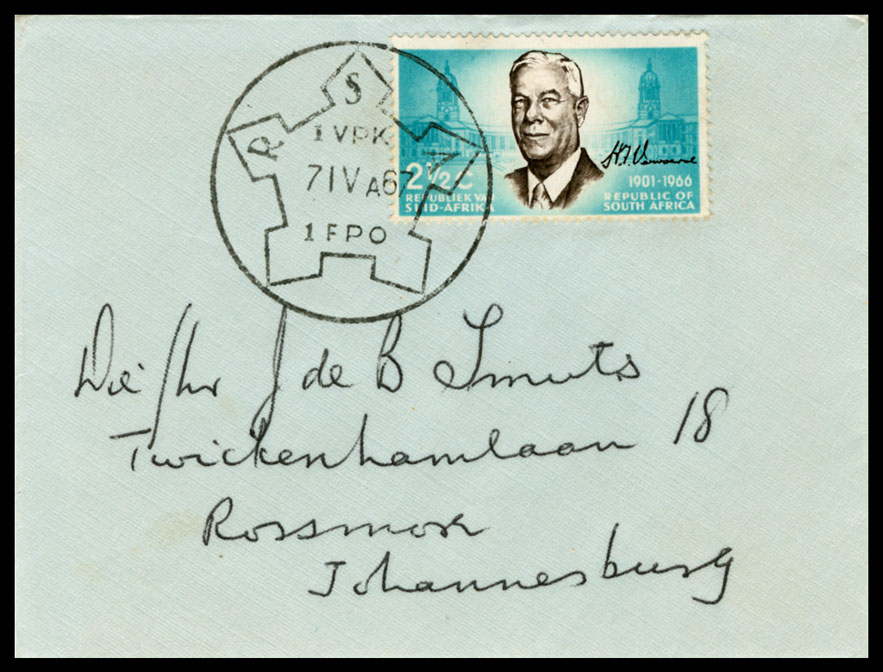

5]. The VOC built a fort, then a Castle, in Cape Town, ostensibly to protect their commercial interests from foreign powers. While exceptions occurred, in reality it protected the Dutch by excluding local people. This was arguably the start of an 'us and them' mindset that soon led to segregation. Ironically, (perhaps not), after South Africa became a republic in 1961, the Castle became the symbol of an almost exclusively White South African Defence Force. On the cover is a 1966 commemorative stamp of the assassinated architect of Apartheid, Dr H. F. Verwoerd. It is cancelled with the 1967 Exercise Spitzkop FPO datestamp showing the SADF emblem taken from the outline of the Castle.

"So what? It was a long time ago and has nothing to do with us today. What's this got to do with philately?".

Having been given a wide-ranging charter by the Dutch government, including the 'right' to trade in slaves, the VOC contributed greatly to the 'Golden Age of Holland' which peaked at about the time van Riebeeck landed at the Cape. The wealth of Holland and Britain today is based to some extent on the misery it inflicted on people - slaves and others - who toiled to exploit profits from their hell-hole colonial adventures.

Following decades of declining profits the VOC was liquidated in 1800. (Its slow financial failure contributed to the difficulties of starting a post office at the Cape in 1792.) The VOC's assets (including slaves) and liabilities accrued to the Batavian Republic ie. the government of Holland. The slave trade continued under the Batavian Republic at the Cape until it was occupied by the British for the second time in 1806. The British ended the slave trade but not slavery at the Cape in 1807. Responsibility for the VOC slave trade lay with the Dutch government who gave them their charter. It is only right that they recognise this was wrong.

Both slavery and stamps were a product of government. The post office is an arm of government subject to the rules of law. Lest you forget, in South Africa the post office was segregated. Those of us who collect stamps or covers are only able to do so because the post office as a warts-and-all arm of government made it possible. The politics of the day, imperial, nationalist, communist, fascist or other are expressed through stamps and covers. Today, many people deride the 'boring' hobby of stamp collecting as something grandpa did. Whatever stamp collecting's detractors have to say about 'the hobby of kings and presidents', many will acknowledge the greater validity and importance of collecting historical items of mail, some of which were posted by trusted slaves in the post office in the Castle, Cape Town, and later in the renovated Slave Lodge until 1834. South Africa's earliest mail has a direct line to slavery via the politics of the day, politics that over time embraced institutional discrimination, segregation and full-blown Apartheid.

Images

1]. Cinderella labels from the Seventh Philatelic Congress of SA, Cape Town, 1938, showing the 6 stuiwe handstamp with the VOC logo and a Cape 'woodblock'. A. A. Jurgens RDPSA FRPSL had a hand in this design.

2]. The 1952 Tercentennary set on stamps! The Dutch commander who repeatedly asked for slaves, the 'father of White South Africa', the 'wrong' Jan van Riebeeck, his vrou, his three ships arriving, his seal of authority and Charles Bell's 'Landing of the Dutch at the Cape', all are nothing less than propaganda pieces for the myth of White South Africa and a Nationalist government hell-bent on implementing Apartheid.

3]. An early sketch of the Slave Lodge built in 1679 to house Cape Town's slaves. In 1658 van Riebeeck received the first large 'consignment' (as in traded 'goods') of slaves. They were housed in and outside the original fort. As this was an impractical long-term arrrangement for housing the rapidly increasing slave population, a 'slave lodge' was built in 1679 alongside the first church of Christian worship in SA at the foot of the Company Gardens. The close proximity between fundamentalist Christianity worship and the practice of slavery saw racial discrimination develop as a way of life in CapeTown. The footbridge centre right spans a drainage ditch, the Heerengracht, (Dutch. the Gentleman's, Lord's or Patrician's Canal).

4]. Weenen Massacre. After the collapse of Khoi culture in the Western Cape, many of the surviving Khoi became 'servants'of the Boers. This wonderfully dramatic painting by Charles Bell no longer enjoys official approval. Here we see Khoi servants fighting alongside their Boer Voortrekker masters against the Zulu in Natal. According to the character of Adendorff, (Gert van den Bergh), in the 1964 movie 'Zulu', the treacherous murder of Boer trekkers established a blood feud between Boer and Zulu. Sadly, the loyalty of the Khoi and other Black servants shown here was never rewarded by the Boers who quickly discarded them.

5]. The VOC built a fort, then a Castle, in Cape Town, ostensibly to protect their commercial interests from foreign powers. While exceptions occurred, in reality it protected the Dutch by excluding local people. This was arguably the start of an 'us and them' mindset that soon led to segregation. Ironically, (perhaps not), after South Africa became a republic in 1961, the Castle became the symbol of an almost exclusively White South African Defence Force. On the cover is a 1966 commemorative stamp of the assassinated architect of Apartheid, Dr H. F. Verwoerd. It is cancelled with the 1967 Exercise Spitzkop FPO datestamp showing the SADF emblem taken from the outline of the Castle.

Uploaded files: