WW1 - SA Heavy Artillery, Cooden Camp, Bexhill-on-Sea

Quote from Steve on September 8, 2025, 3:40 pmIn July 1915, Prime Minsier General Louis Botha, the victor in the German South West Africa campaign, offered to support the war in Europe with 4 South African infantry battalions, 5 heavy artillery batteries, a general hospital and a signal company. The heavy artillery batteries were affiliated to the British Royal Garrison Artillery as the 71st (Transvaal), 72nd (Griqualand West), 73rd (Western Cape), 74th (Eastern Province) and the 75th (Natal). Later a 6th battery, the 125th (Transvaal) was formed. All were armed with 6" howitzers.

The force embarked at Cape Town between 28 August and 17 October 1915 and all units involved were in England by November. The artillerymen moved to Cooden Camp, a British military training camp near Bexhill-0n-Sea which had been established at the start of WW1 on farmland. Initially the occupants of the camp were housed under canvas in a Lower Camp near the parade ground. By the end of 1914 wooden huts were constructed in an Upper Camp. The role and occupancy of Cooden Camp varied throughout the war.

1915. Real Phto Postcard. BEXHILL-ON-SEA ' 22 OC 15' to RETREAT, CP, SOUTH AFRICA 'NO 13 15'.

'The Night Hawks. S.A.H.A. Cooden Camp. II.T." (Photo by Geo. Chapman, Station Rd., Bexhill.)

Note that the Night Hawks are outside wooden huts "constructed .... at the end 1914".

Note: None have cap badges but most appear to wear metal shoulder titles.

These men were probably proud, loud and brash - and tight as ticks!With the arrival of the 700 strong detachment of SAHA (South African Heavy Artillery) in September 1915 the atmosphere in Cooden Camp changed. Having recently won the victorious German South Western African campaign, the first major Allied military success of the war, one entirely controlled by South African, not British, staff officers, these men were probably proud, loud and brash with the confidence to tell all who would listen that if left to the South Africans the Germans would be finished in weeks. These men were soon joined by two depots (training units) of the Royal Garrison Artillery, as well as other British and Australian artillerymen.

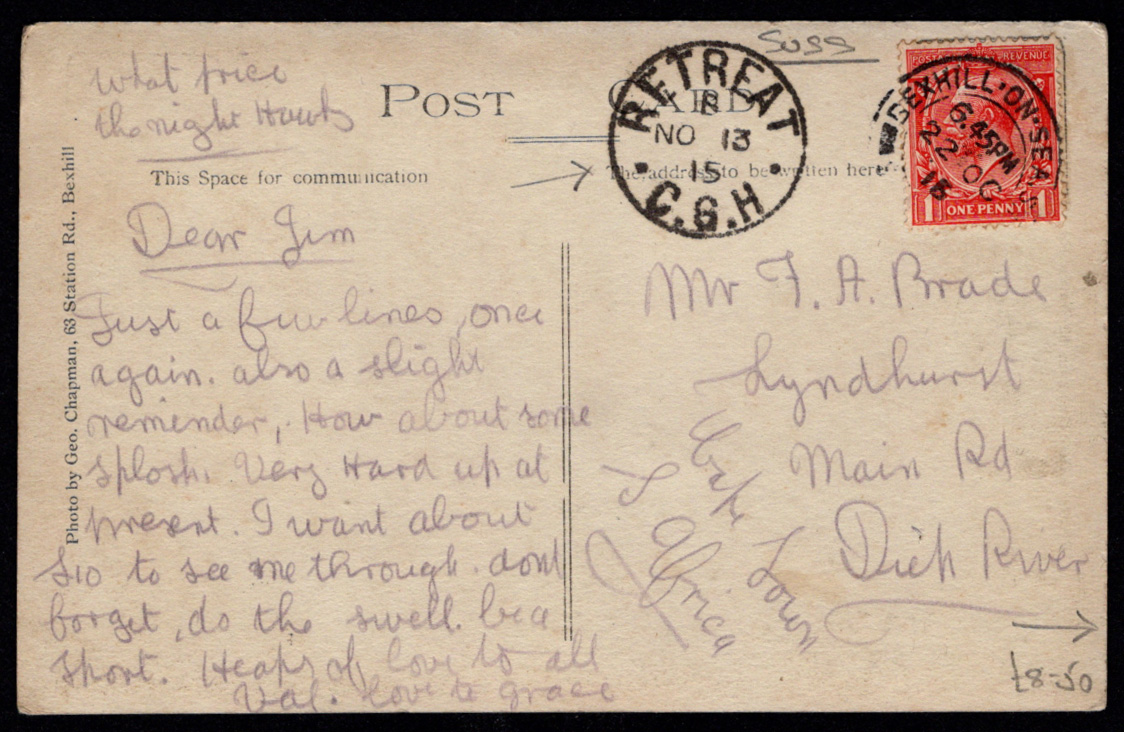

1915. Reverse of Postcard above. Late use of Colonial C.G.H datestamp.

"What price the night hawks. Dear Jim, Just a few lines once again, also a slight reminder. How about some splosh. Very hard up at present. I want about £10 to see me through. Don't forget, do the swell, be a sport. Heaps of love to all. Love to Grace. Val".The camp would remain an artillery training post for the next 18 months.At the end of their training in Cooden Camp the artillerymen proceeded to firing training in Lydd, Kent. The SAHA's five batteries of 6-inch howitzers deployed to the Western Front in 1916, where they fought under Royal Garrison Artillery command. The SAHA suffered 277 casualties including 26 deaths, many due to mustard gas. When the Germans launched their do-or-die Spring Offensive in March 1918 they made such a rapid advance that the gunners of 73rd (SA) Battery had to defend their guns with rifles, suffering heavy casualties. The 73rd Battery was drawn from the Western Cape. As the postcard above is being sent to Retreat, it suggest the lads in the photo were in the 73rd Battery.)

The SAHA was demobilised after the Armistice.

In July 1915, Prime Minsier General Louis Botha, the victor in the German South West Africa campaign, offered to support the war in Europe with 4 South African infantry battalions, 5 heavy artillery batteries, a general hospital and a signal company. The heavy artillery batteries were affiliated to the British Royal Garrison Artillery as the 71st (Transvaal), 72nd (Griqualand West), 73rd (Western Cape), 74th (Eastern Province) and the 75th (Natal). Later a 6th battery, the 125th (Transvaal) was formed. All were armed with 6" howitzers.

The force embarked at Cape Town between 28 August and 17 October 1915 and all units involved were in England by November. The artillerymen moved to Cooden Camp, a British military training camp near Bexhill-0n-Sea which had been established at the start of WW1 on farmland. Initially the occupants of the camp were housed under canvas in a Lower Camp near the parade ground. By the end of 1914 wooden huts were constructed in an Upper Camp. The role and occupancy of Cooden Camp varied throughout the war.

1915. Real Phto Postcard. BEXHILL-ON-SEA ' 22 OC 15' to RETREAT, CP, SOUTH AFRICA 'NO 13 15'.

'The Night Hawks. S.A.H.A. Cooden Camp. II.T." (Photo by Geo. Chapman, Station Rd., Bexhill.)

Note that the Night Hawks are outside wooden huts "constructed .... at the end 1914".

Note: None have cap badges but most appear to wear metal shoulder titles.

These men were probably proud, loud and brash - and tight as ticks!

With the arrival of the 700 strong detachment of SAHA (South African Heavy Artillery) in September 1915 the atmosphere in Cooden Camp changed. Having recently won the victorious German South Western African campaign, the first major Allied military success of the war, one entirely controlled by South African, not British, staff officers, these men were probably proud, loud and brash with the confidence to tell all who would listen that if left to the South Africans the Germans would be finished in weeks. These men were soon joined by two depots (training units) of the Royal Garrison Artillery, as well as other British and Australian artillerymen.

1915. Reverse of Postcard above. Late use of Colonial C.G.H datestamp.

"What price the night hawks. Dear Jim, Just a few lines once again, also a slight reminder. How about some splosh. Very hard up at present. I want about £10 to see me through. Don't forget, do the swell, be a sport. Heaps of love to all. Love to Grace. Val".

The camp would remain an artillery training post for the next 18 months.At the end of their training in Cooden Camp the artillerymen proceeded to firing training in Lydd, Kent. The SAHA's five batteries of 6-inch howitzers deployed to the Western Front in 1916, where they fought under Royal Garrison Artillery command. The SAHA suffered 277 casualties including 26 deaths, many due to mustard gas. When the Germans launched their do-or-die Spring Offensive in March 1918 they made such a rapid advance that the gunners of 73rd (SA) Battery had to defend their guns with rifles, suffering heavy casualties. The 73rd Battery was drawn from the Western Cape. As the postcard above is being sent to Retreat, it suggest the lads in the photo were in the 73rd Battery.)

The SAHA was demobilised after the Armistice.

Quote from Jamie Smith on September 8, 2025, 7:19 pmThe signals were stationed in Eastern England and were reponsabe for the network of telegraph poles through that area. I only know of two heavy guns in S.A. one was at the Union Building in Pretoria and the other was in a Zoo, I think it was Johannesburg. I only remember one other gun but that was a Turkish field gun that poked over a garden wall in Duncanville, Vereeniging, that one was brought back from Mesopotamia by the Cape Corps. Regarding the shoulder tags, I know orange tags were worn in WW2 to show that the wearer had volunteered for overseas service; it may have also applied in WW1.

Some of the SA troops, were sent to North Africa (under Gen. Lukin) by the British High command on the theory was that coming from Africa, they were used to African conditions. Those still in UK were sent to the Western front, - Delville Wood was one of the engagements. At the end of the war, many enlisted in the British Army and served in Northern Russia -1919.

The signals were stationed in Eastern England and were reponsabe for the network of telegraph poles through that area. I only know of two heavy guns in S.A. one was at the Union Building in Pretoria and the other was in a Zoo, I think it was Johannesburg. I only remember one other gun but that was a Turkish field gun that poked over a garden wall in Duncanville, Vereeniging, that one was brought back from Mesopotamia by the Cape Corps. Regarding the shoulder tags, I know orange tags were worn in WW2 to show that the wearer had volunteered for overseas service; it may have also applied in WW1.

Some of the SA troops, were sent to North Africa (under Gen. Lukin) by the British High command on the theory was that coming from Africa, they were used to African conditions. Those still in UK were sent to the Western front, - Delville Wood was one of the engagements. At the end of the war, many enlisted in the British Army and served in Northern Russia -1919.