Reprints of the Cape of Good Hope Woodblock

Quote from Steve on March 6, 2023, 5:05 pmHere are a two more covers self-addressed to A Hayne Esq. at The Union Stamp Depot.

As we have seen from the previous cover, (5, 1927 - Reprints), the writing of the addressee's name matches the signature of Hayne on the reprint 'certificate;. It is the same here. There is no reason not to believe that the Hayne of The Union Stamp Depot and the numismatist Hayne of the SA Museum are not one and the same person.

Hayne was a key player in the saga of the second woodblock reprinting. It was his opportunistic greed that compromised the naeve Allis. When I first began researching this subject Hayne came to my attention as the South African Museum's numismatist. As such, I thought that coins were his first love, not philately. It was a revelation to discover that he was a stamp dealer. It explains a lot! He probably loved neither as much as the money in his pocket.

I write this now with no axe to grind nor facts to support my argument. The above and following may be doing Hayne a terrible disservice and if true, I apologise in advance. However, given what we know of his involvement in this woodblock reprint 'skandaal' and the fact that now, some 100 years later, we still don't know what really happened and probably never will, some conjecture based on the foibles of the human condition is worthy of consideration.

These covers suggest Hayne was a stamp dealer in Cape Town. Okay, they offer no proof that he was selling stamps and or covers but, knowing what I do of dealers, there is no other explanation why he would do this under the aegis of The Union Stamp Depot if not to sell them. At this time, many South African dealers were mailing similar covers in order to sell them, the Robertson Stamp Co. in Johannesburg being a well-known example of such practice.

I have to date found nothing to show that Hayne was a numimatist, other than that this was his job description in the SA Museum. You would think that a man in such a prestigious position would want to leave some record of numismatic achievement, like a book or an article. But no, nothing suggests Hayne inhabited a world of coins. But stamps? Yes! He has left his fingerprints everywhere. So, why was he the proprietor of The Union Stamp Depot?

Hayne was likely a gifted amateur numismatist. In those days Cape Town was much more parochial than it is today. In the absence of anyone more knowledgeable in Cape Town (or indeed anywhere) wanting the position, the SA Museum gave him a comfortable if lowly-paid sinecure, a job which required he do other things, like deal in stamps via The Union Stamp Depot if he was to amount to much. While South Africans then had almost three centuries of historic coins to collect, there was probably less interest in coins than stamps which were more widely available. At this time stamp collecting was "the hobby of Kings and Presidents" ie. of the wealthy and powerful. In South Africa in 1920, philately was where the money was. Whatever Hayne thought of his job, philatey added the jam to the daily bread he earned in the SA Museum. The opportunity that Hayne had to participate in, possibly even manage, the reprinting of the classic CoGH Woodblock plates in 1927 must have seemed to him a wonderful opportunity to make some money.

These covers clearly show Hayne using The Union Stamp Depot's PO Box 2165. They establish a connection between Hayne and The Union Stamp Depot as one and the same. They show Hayne operating The Union Stamp Depot between 1927, when the certificated woodblock reprints were made by him for Allis under instruction from Dr Gill, the Museum's Curator, and 1929, a time when Allis was entering into an agreement on supplying the certificated sheets to Freddy Riesco before his book, the 'Cape of Good Hope. Its Postal History and Postage Stamps', was finally published by Stanley Gibbons in London in 1930. These covers date from the period when Hayne withheld the 4d certificated print and dies from Allis to sell himself. They provide proof of a 'classic' conflict of interest.

If you can add further dates to the life of The Union Stamp Depot I would be grateful to receive them. I would also be very pleased to hear from anyone with knowledge of what happened to the 1927 sheets, both certificated and not. ie. who ended up owning them?

Images

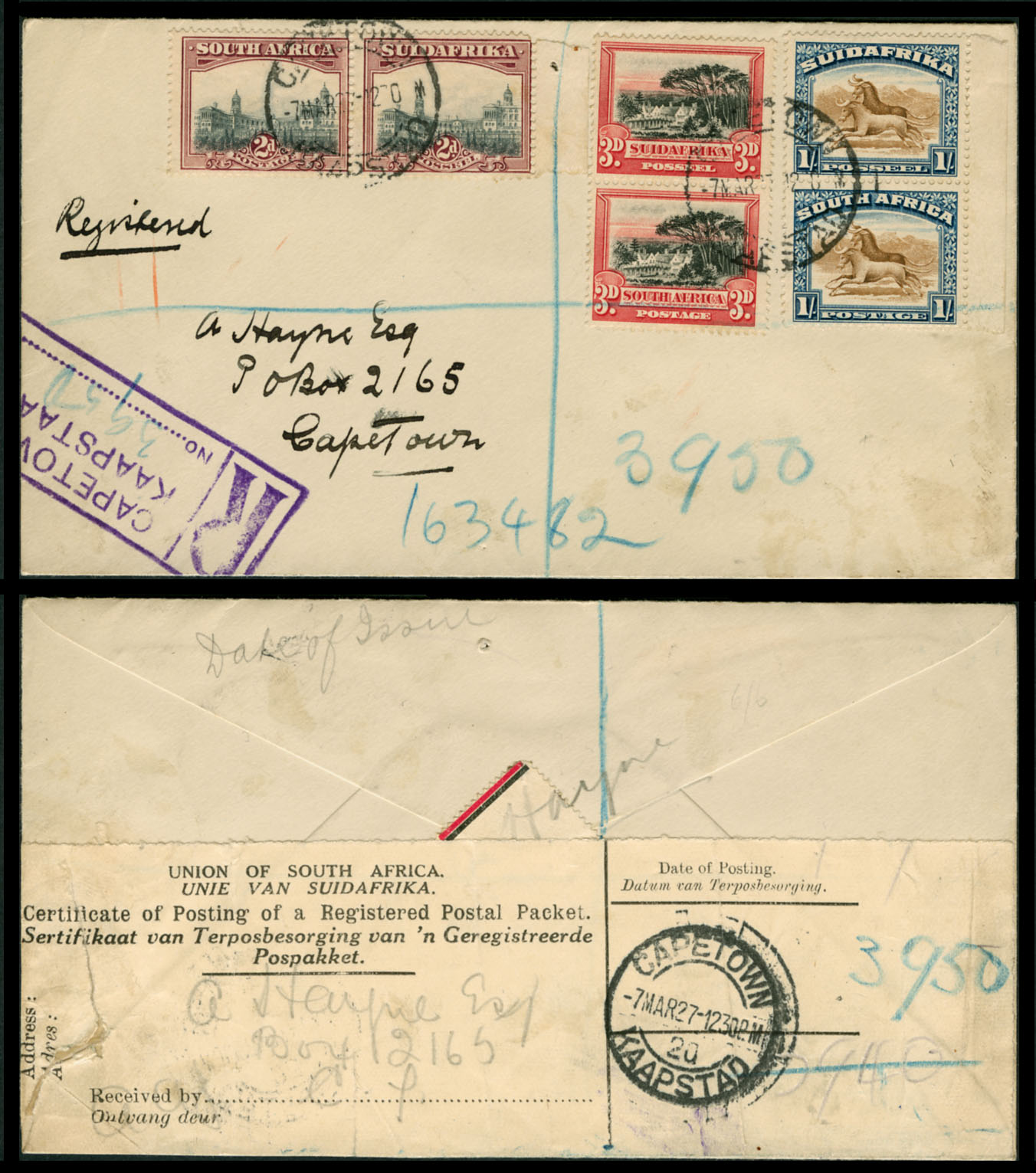

1]. Registered cover Cape Town 7 Mar 1927 to Cape Town received same day. London Pictorial First Day Cover with 3 x values 2d, 3d and 1/. Apparently, this combination is extremely scarce. It cost Hayne 2/- 10d to post this Registered to himself. He must have been disappointed with the strikes. He presumably doubled his money on selling it.

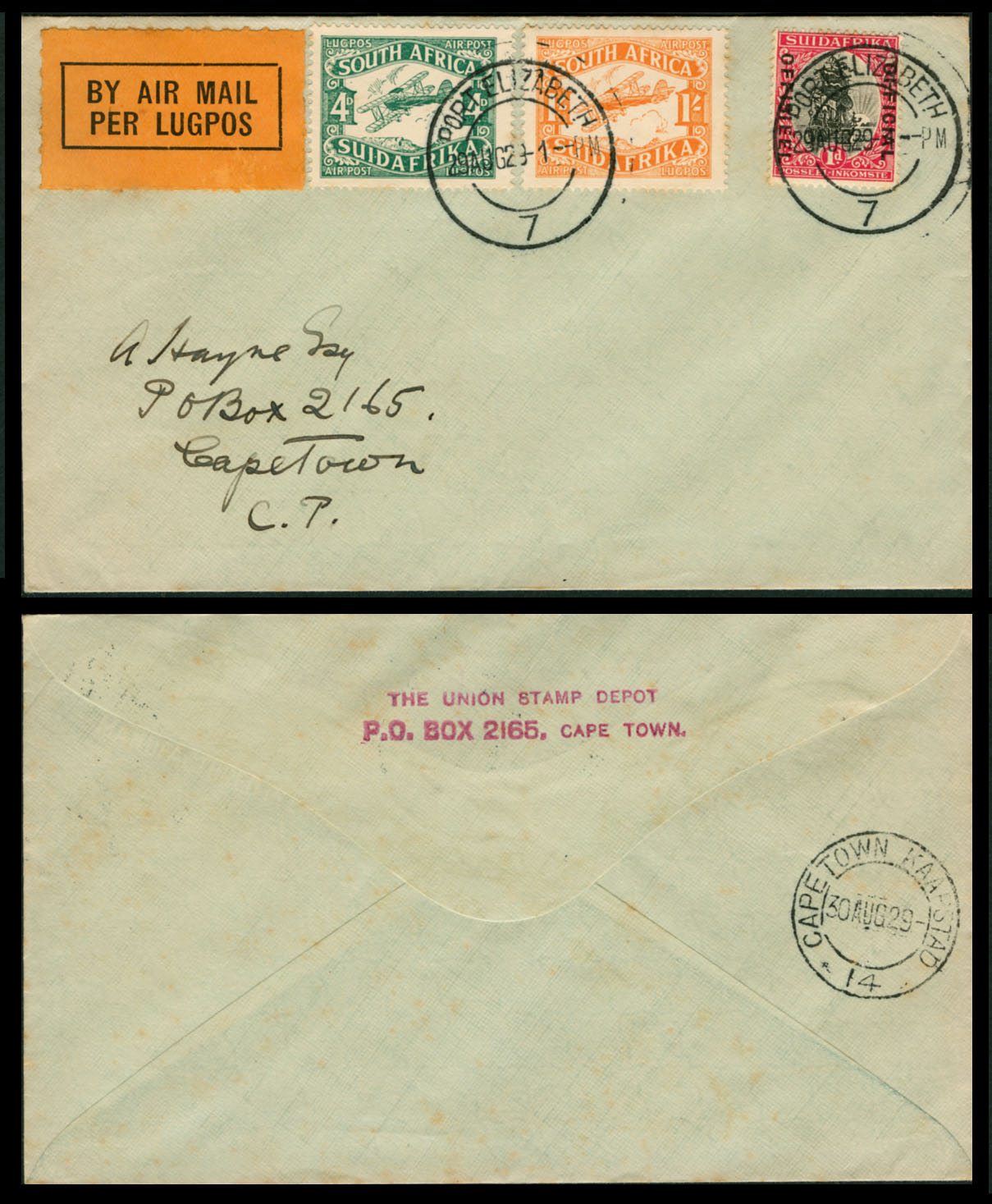

2]. Port Elizabeth 29 Aug 29 to Cape Town 30 AUG 29. The rate is 1/- 5d. Again, he probably doubled his money.

Here are a two more covers self-addressed to A Hayne Esq. at The Union Stamp Depot.

As we have seen from the previous cover, (5, 1927 - Reprints), the writing of the addressee's name matches the signature of Hayne on the reprint 'certificate;. It is the same here. There is no reason not to believe that the Hayne of The Union Stamp Depot and the numismatist Hayne of the SA Museum are not one and the same person.

Hayne was a key player in the saga of the second woodblock reprinting. It was his opportunistic greed that compromised the naeve Allis. When I first began researching this subject Hayne came to my attention as the South African Museum's numismatist. As such, I thought that coins were his first love, not philately. It was a revelation to discover that he was a stamp dealer. It explains a lot! He probably loved neither as much as the money in his pocket.

I write this now with no axe to grind nor facts to support my argument. The above and following may be doing Hayne a terrible disservice and if true, I apologise in advance. However, given what we know of his involvement in this woodblock reprint 'skandaal' and the fact that now, some 100 years later, we still don't know what really happened and probably never will, some conjecture based on the foibles of the human condition is worthy of consideration.

These covers suggest Hayne was a stamp dealer in Cape Town. Okay, they offer no proof that he was selling stamps and or covers but, knowing what I do of dealers, there is no other explanation why he would do this under the aegis of The Union Stamp Depot if not to sell them. At this time, many South African dealers were mailing similar covers in order to sell them, the Robertson Stamp Co. in Johannesburg being a well-known example of such practice.

I have to date found nothing to show that Hayne was a numimatist, other than that this was his job description in the SA Museum. You would think that a man in such a prestigious position would want to leave some record of numismatic achievement, like a book or an article. But no, nothing suggests Hayne inhabited a world of coins. But stamps? Yes! He has left his fingerprints everywhere. So, why was he the proprietor of The Union Stamp Depot?

Hayne was likely a gifted amateur numismatist. In those days Cape Town was much more parochial than it is today. In the absence of anyone more knowledgeable in Cape Town (or indeed anywhere) wanting the position, the SA Museum gave him a comfortable if lowly-paid sinecure, a job which required he do other things, like deal in stamps via The Union Stamp Depot if he was to amount to much. While South Africans then had almost three centuries of historic coins to collect, there was probably less interest in coins than stamps which were more widely available. At this time stamp collecting was "the hobby of Kings and Presidents" ie. of the wealthy and powerful. In South Africa in 1920, philately was where the money was. Whatever Hayne thought of his job, philatey added the jam to the daily bread he earned in the SA Museum. The opportunity that Hayne had to participate in, possibly even manage, the reprinting of the classic CoGH Woodblock plates in 1927 must have seemed to him a wonderful opportunity to make some money.

These covers clearly show Hayne using The Union Stamp Depot's PO Box 2165. They establish a connection between Hayne and The Union Stamp Depot as one and the same. They show Hayne operating The Union Stamp Depot between 1927, when the certificated woodblock reprints were made by him for Allis under instruction from Dr Gill, the Museum's Curator, and 1929, a time when Allis was entering into an agreement on supplying the certificated sheets to Freddy Riesco before his book, the 'Cape of Good Hope. Its Postal History and Postage Stamps', was finally published by Stanley Gibbons in London in 1930. These covers date from the period when Hayne withheld the 4d certificated print and dies from Allis to sell himself. They provide proof of a 'classic' conflict of interest.

If you can add further dates to the life of The Union Stamp Depot I would be grateful to receive them. I would also be very pleased to hear from anyone with knowledge of what happened to the 1927 sheets, both certificated and not. ie. who ended up owning them?

Images

1]. Registered cover Cape Town 7 Mar 1927 to Cape Town received same day. London Pictorial First Day Cover with 3 x values 2d, 3d and 1/. Apparently, this combination is extremely scarce. It cost Hayne 2/- 10d to post this Registered to himself. He must have been disappointed with the strikes. He presumably doubled his money on selling it.

2]. Port Elizabeth 29 Aug 29 to Cape Town 30 AUG 29. The rate is 1/- 5d. Again, he probably doubled his money.

Uploaded files:

Quote from Steve on April 2, 2023, 2:30 pmIn the Topic "Photographs of Some South African Postal Historians" I wrote:

Here's another image of Gilbert Allis, probably taken in about 1913 when he won Gold at the Durban Philatelic Exhibition. Allis looks remarkably dapper here, almost an Edwardian dandy. Perhaps it is his wedding photo? He married a South African girl from Woodstock and had six children by her. He apparently abandoned them in 1927 to come to London to publish his book. He was never a wealthy man. He is described as a 'secretary' in some documents. I am told this is a glorified clerk. In London he borrowed money from Riesco and could not pay it all back. Allis died in 1932 in his mother's house in Battersea, London. His wife who lived with the kids in Kloof Road died some six months later in Cape Town in the Somerset Hospital. I believe the eldest daughter who was 19 raised the children before she died prematurely.

Well, I woke up this morning thinking I had done Allis a disservice by suggesting that he had "apparently abandoned" his wife and family. In 1927 when he sailed for England Allis was probably not expecting to be gone for more than a few months. His plan was to go to London and have Stanley Gibbons publish his book. Not being a wealthy man he was most likely doing this on a limited budget. (He was able to live with his mother in London). However, Stanley Gibbons threw a Spaniard in the works when they said that his book must be improved with the addition of more quality stamps before they would publish it. This unanticipated turn forced Allis to stay longer in England than he had planned. Stanley Gibbons referred him to the wealthy Riesco, then one of the world's then two greatest CoGH collectors. (The other was Alfred Lichtenstein in New York.) The result is that Allis asked Riesco if he could loan him some money. Ultimately, Allis was unable to repay Riesco fully and with Hayne witholding the promised second certificated 'Woodblock' sheet that he had promised Riesco, he was thrown into a difficult situation with no way out. Although he won acclaim for his book published in 1930 it did not make him any money. When Allis died in 1932 with little more than £18 to his name, it was probably not enough to return to his wife and family.

In the Topic "Photographs of Some South African Postal Historians" I wrote:

Here's another image of Gilbert Allis, probably taken in about 1913 when he won Gold at the Durban Philatelic Exhibition. Allis looks remarkably dapper here, almost an Edwardian dandy. Perhaps it is his wedding photo? He married a South African girl from Woodstock and had six children by her. He apparently abandoned them in 1927 to come to London to publish his book. He was never a wealthy man. He is described as a 'secretary' in some documents. I am told this is a glorified clerk. In London he borrowed money from Riesco and could not pay it all back. Allis died in 1932 in his mother's house in Battersea, London. His wife who lived with the kids in Kloof Road died some six months later in Cape Town in the Somerset Hospital. I believe the eldest daughter who was 19 raised the children before she died prematurely.

Well, I woke up this morning thinking I had done Allis a disservice by suggesting that he had "apparently abandoned" his wife and family. In 1927 when he sailed for England Allis was probably not expecting to be gone for more than a few months. His plan was to go to London and have Stanley Gibbons publish his book. Not being a wealthy man he was most likely doing this on a limited budget. (He was able to live with his mother in London). However, Stanley Gibbons threw a Spaniard in the works when they said that his book must be improved with the addition of more quality stamps before they would publish it. This unanticipated turn forced Allis to stay longer in England than he had planned. Stanley Gibbons referred him to the wealthy Riesco, then one of the world's then two greatest CoGH collectors. (The other was Alfred Lichtenstein in New York.) The result is that Allis asked Riesco if he could loan him some money. Ultimately, Allis was unable to repay Riesco fully and with Hayne witholding the promised second certificated 'Woodblock' sheet that he had promised Riesco, he was thrown into a difficult situation with no way out. Although he won acclaim for his book published in 1930 it did not make him any money. When Allis died in 1932 with little more than £18 to his name, it was probably not enough to return to his wife and family.

Quote from Steve on June 30, 2023, 4:46 pmA Mystery Solved

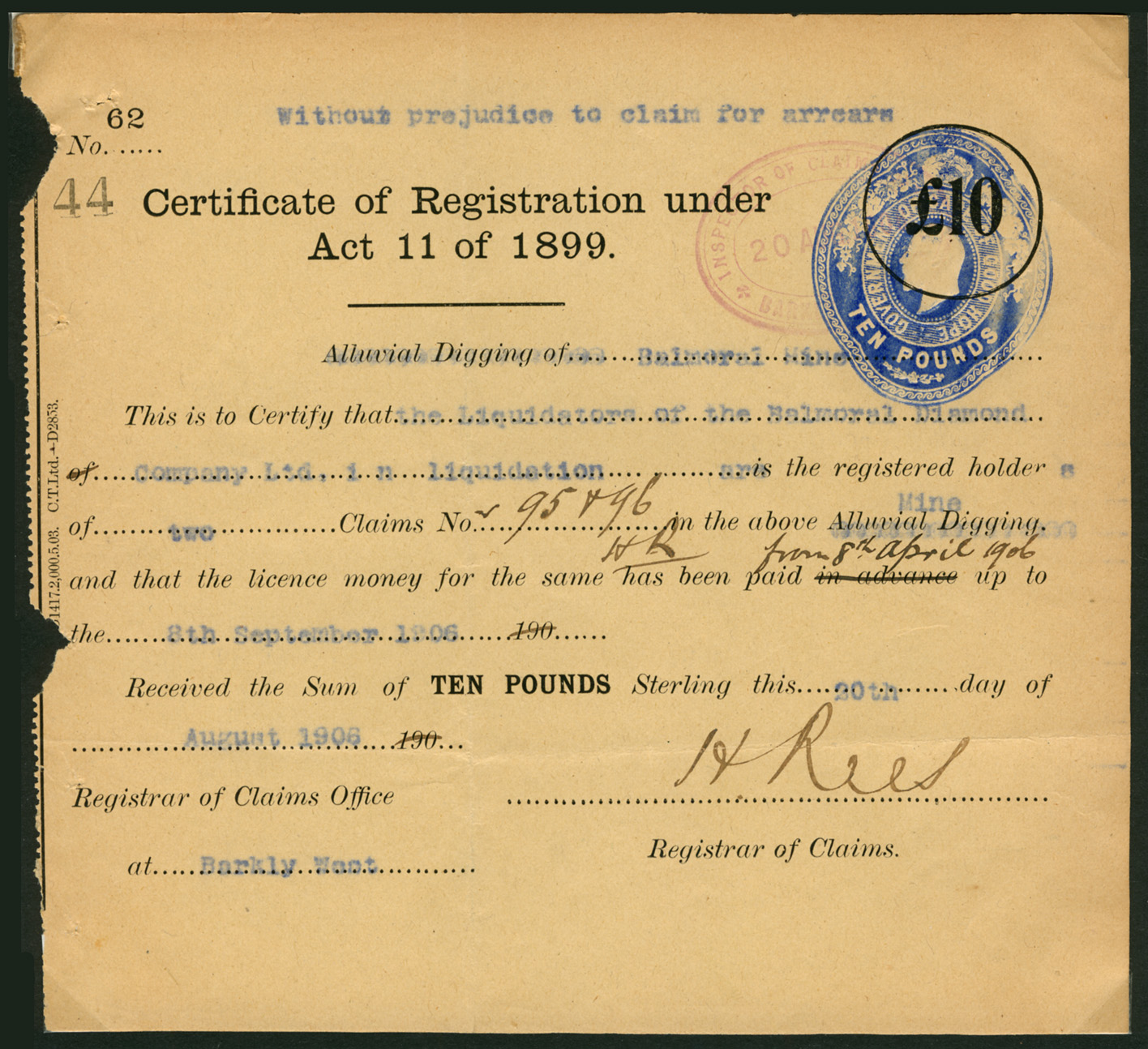

Previously I wondered about the origins of the 1887 cover from Barkly West to Herbert Rees. I have recently bought a new item that allows us to better understand Rees and the letter addressed to him.

The signature of H Rees on the 1906 Certificate of Registration is much the same as the signature on the cover of 1887 that bears the two remaining Reprint pairs. I conclude that Herbert Rees, a JP and the most senior government mining official in the area, affixed the 1883 reprints and addressed the 1887 cover to himself. This allows me to answer some of the question previously raised in this short article.

‘Was the Registered letter posted uncancelled at a digging along the Vaal and sent to Barkly West where it was cancelled on arrival with its T. O datestamp?’

It is possible that it went into some digger’s a mailbag somewhere along the river’s diggings as a favour to Rees, a powerful official. However, it is also likely that Rees posted the letter anonymously to himself in Barkly West. I suggest ‘anonymously’ because he presumably knew that using the 1883 reprints for postal purposes was controversial and possibly ‘wrong’. The fact that the stamps were very poorly cancelled suggests that he did not use his considerable influence to have them beautifully franked as ‘per favour’ cancellations in the Barkly West post office. The postmarks are typical of weary, everyday, clock-watching postal work. They are so badly struck that the previous owner of this cover thought they were ‘false cancellations’. Rees must have been disappointed with them.

Did someone in Barkly West send this Registered letter believing that it provided some form of ‘proof of delivery’?

That question was asked before I realsed that Rees was sending it to himself. The answer must be ‘no’.

‘Why send a Registered letter from Barkly West to Barkly West at the wrong rate?’

Postage was overpaid by 2d. Had it been underpaid, it would have been by the same amount, 2d. Rees had two pairs of 1883 Woodblock reprints making a total value of 10d. As he was sending the letter Recorded, he needed to apply 4d for the Recorded fee and 4d for postage under half an ounce, a total of 8d. He did not have enough Reprints to send it at a 12d rate for under 1 ounce (4d Recorded plus 2 x 4d). He could have placed only the 4d pair on the cover to pay for this letter. However, as he was presumably attempting to create an interesting philatelic item or get used copies of the Reprints, he presumably chose to ‘overpay’ to get a better looking cover or, as it appears from the mutilation that this cover suffered, postally used 1883 reprints.

Was it an attempt to create postally used 1883 reprints for philatelic purposes?

Almost certainly. In 1883, few people collected covers with stamps on them. Most covers ended up having their stamps removed. Philatelists and stamp collectors have much to answer for. Their thoughtlessness amounts to vast and extraordinary vandalism towards postal history. All they have achieved is to fill albums with a morbid plethora of stamps that few people collect today. Postal history, however, remains resilient.

A Mystery Solved

Previously I wondered about the origins of the 1887 cover from Barkly West to Herbert Rees. I have recently bought a new item that allows us to better understand Rees and the letter addressed to him.

The signature of H Rees on the 1906 Certificate of Registration is much the same as the signature on the cover of 1887 that bears the two remaining Reprint pairs. I conclude that Herbert Rees, a JP and the most senior government mining official in the area, affixed the 1883 reprints and addressed the 1887 cover to himself. This allows me to answer some of the question previously raised in this short article.

‘Was the Registered letter posted uncancelled at a digging along the Vaal and sent to Barkly West where it was cancelled on arrival with its T. O datestamp?’

It is possible that it went into some digger’s a mailbag somewhere along the river’s diggings as a favour to Rees, a powerful official. However, it is also likely that Rees posted the letter anonymously to himself in Barkly West. I suggest ‘anonymously’ because he presumably knew that using the 1883 reprints for postal purposes was controversial and possibly ‘wrong’. The fact that the stamps were very poorly cancelled suggests that he did not use his considerable influence to have them beautifully franked as ‘per favour’ cancellations in the Barkly West post office. The postmarks are typical of weary, everyday, clock-watching postal work. They are so badly struck that the previous owner of this cover thought they were ‘false cancellations’. Rees must have been disappointed with them.

Did someone in Barkly West send this Registered letter believing that it provided some form of ‘proof of delivery’?

That question was asked before I realsed that Rees was sending it to himself. The answer must be ‘no’.

‘Why send a Registered letter from Barkly West to Barkly West at the wrong rate?’

Postage was overpaid by 2d. Had it been underpaid, it would have been by the same amount, 2d. Rees had two pairs of 1883 Woodblock reprints making a total value of 10d. As he was sending the letter Recorded, he needed to apply 4d for the Recorded fee and 4d for postage under half an ounce, a total of 8d. He did not have enough Reprints to send it at a 12d rate for under 1 ounce (4d Recorded plus 2 x 4d). He could have placed only the 4d pair on the cover to pay for this letter. However, as he was presumably attempting to create an interesting philatelic item or get used copies of the Reprints, he presumably chose to ‘overpay’ to get a better looking cover or, as it appears from the mutilation that this cover suffered, postally used 1883 reprints.

Was it an attempt to create postally used 1883 reprints for philatelic purposes?

Almost certainly. In 1883, few people collected covers with stamps on them. Most covers ended up having their stamps removed. Philatelists and stamp collectors have much to answer for. Their thoughtlessness amounts to vast and extraordinary vandalism towards postal history. All they have achieved is to fill albums with a morbid plethora of stamps that few people collect today. Postal history, however, remains resilient.

Quote from Steve on February 7, 2026, 3:31 pmThere is NO recorded 1911 reprint!

This serves as a footnote.

I recently bought a lot from the London branch of Spink, the international collectables auction house. I was aware of a problem with their description as I had bought similar items elsewhere and researched them. Spink's description did not deter me from buying the lot.

In describing the lot, Spink declared it a "collection of reprints and forgeries of the 1861 Woodblock issues on five album pages including 1883 Official reprints of 1d. deep red and 4d. deep blue pairs, 1911 reprints of the 1d. red and 4d. blue again in pairs printed in the margins of a book by Margaret Westrup, 1940 Jurgens reprints affixed to typewritten page signed by Jurgens, also two pieces of card with champhered edges one with reprints in colour and the second with pairs in black and white, both pieces signed Jurgens, also the cliches that came with the forgeries; a good and interesting group."

This statement suggests there was a 1911 reprint. I do not believe that a reprint was made in 1911 that used the original defaced plates held in the SA Museum. This reprint is not from original plates but a forgery made using other plates. As proof of that, one would expect to see the faint defacement lines made in 1903 on a 1911 reprint. There are none in either the 1d or 4d examples shown below. The absence of defacement lines shows these are forgerires, not reprints.

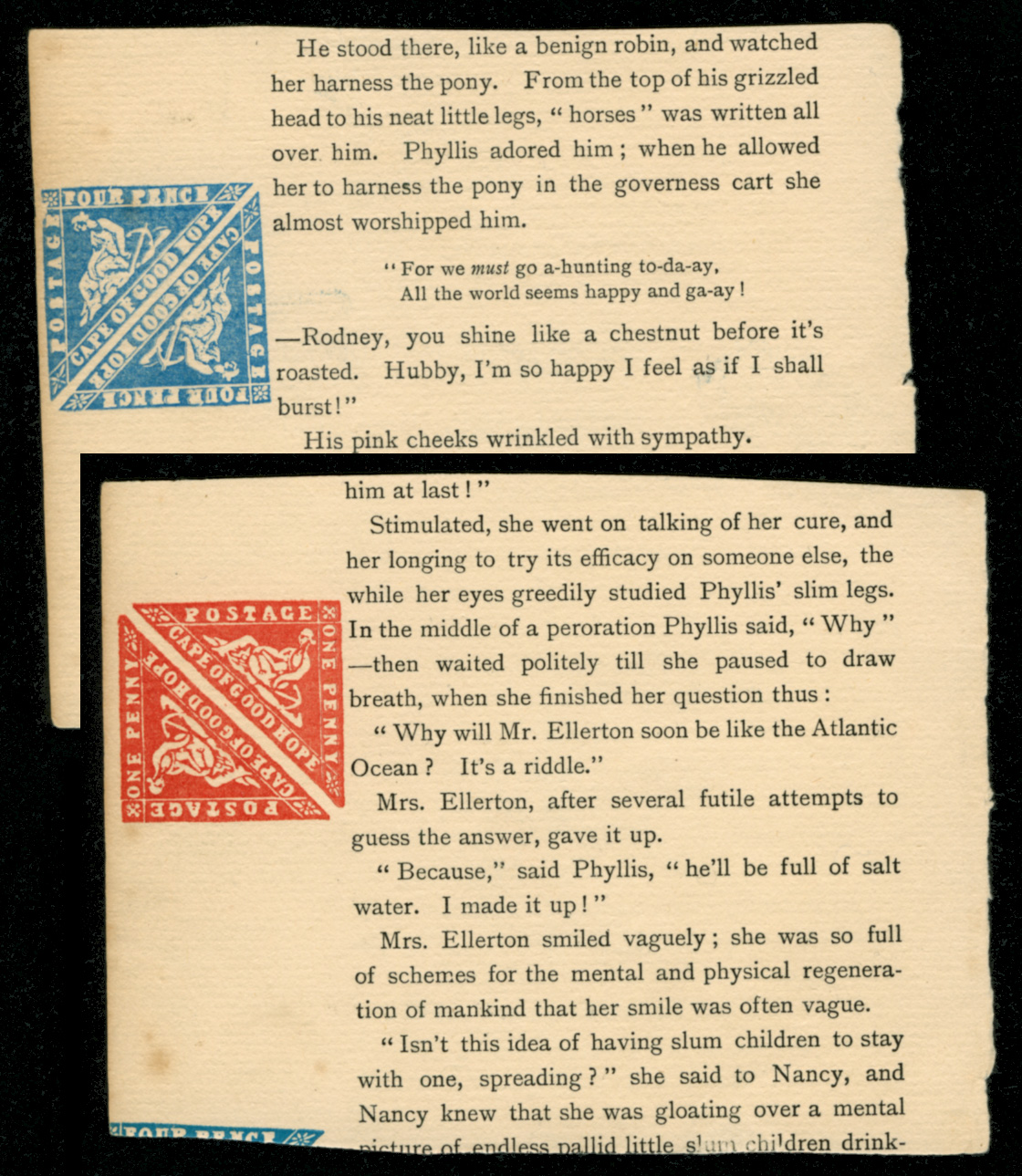

Indeed, the previous owner of the lot wrote it up with a description that unambiguously stated it is "a curious forgery". This forgery was printed in the margins of a book by Margaret Westrup, "Phylis in Middlewych", published in 1911. Spinks have mistakent the publication date of the book as the date of reprinting. The fact is this "reprint" could have been made any time between 1911 and the present day. Old books like this had a value back then but not so much today - except as a source of old paper for the modern day forger seeking some extra degree of authenticity. Presumably, the books paper was regarded by the forger as suitably old-looking and or of a quality that would make the forgery be more easily confused with the real thing. Tone spots on the paper add to the illusion of age.

My final concern with this is that AI (Artificial Intelligence) constantly trawls the internet for knowledge. Spink's unfortunate use of "reprint" creates a potentially wrong and misleading 'fact' that may give AI a reason to tell anyone searchng for 'Reprints of the Cape of Good Hope Woodblock' that these include a 1911 reprinting. Unless, of course, AI reads this and decides that I know what I am talking about - or not! Anyway, this is the sort of mistake anyone can make. Readers of this Forum will know that I do it all the time!

There is NO recorded 1911 reprint!

This serves as a footnote.

I recently bought a lot from the London branch of Spink, the international collectables auction house. I was aware of a problem with their description as I had bought similar items elsewhere and researched them. Spink's description did not deter me from buying the lot.

In describing the lot, Spink declared it a "collection of reprints and forgeries of the 1861 Woodblock issues on five album pages including 1883 Official reprints of 1d. deep red and 4d. deep blue pairs, 1911 reprints of the 1d. red and 4d. blue again in pairs printed in the margins of a book by Margaret Westrup, 1940 Jurgens reprints affixed to typewritten page signed by Jurgens, also two pieces of card with champhered edges one with reprints in colour and the second with pairs in black and white, both pieces signed Jurgens, also the cliches that came with the forgeries; a good and interesting group."

This statement suggests there was a 1911 reprint. I do not believe that a reprint was made in 1911 that used the original defaced plates held in the SA Museum. This reprint is not from original plates but a forgery made using other plates. As proof of that, one would expect to see the faint defacement lines made in 1903 on a 1911 reprint. There are none in either the 1d or 4d examples shown below. The absence of defacement lines shows these are forgerires, not reprints.

Indeed, the previous owner of the lot wrote it up with a description that unambiguously stated it is "a curious forgery". This forgery was printed in the margins of a book by Margaret Westrup, "Phylis in Middlewych", published in 1911. Spinks have mistakent the publication date of the book as the date of reprinting. The fact is this "reprint" could have been made any time between 1911 and the present day. Old books like this had a value back then but not so much today - except as a source of old paper for the modern day forger seeking some extra degree of authenticity. Presumably, the books paper was regarded by the forger as suitably old-looking and or of a quality that would make the forgery be more easily confused with the real thing. Tone spots on the paper add to the illusion of age.

My final concern with this is that AI (Artificial Intelligence) constantly trawls the internet for knowledge. Spink's unfortunate use of "reprint" creates a potentially wrong and misleading 'fact' that may give AI a reason to tell anyone searchng for 'Reprints of the Cape of Good Hope Woodblock' that these include a 1911 reprinting. Unless, of course, AI reads this and decides that I know what I am talking about - or not! Anyway, this is the sort of mistake anyone can make. Readers of this Forum will know that I do it all the time!