My writings.

Quote from Jamie Smith on September 29, 2020, 6:43 amA change of scene.

A change of scene.

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on September 30, 2020, 6:20 amBetween Vereeniging and Vanderbijlpark there used to be a vlei. I stopped at the side of the road many times to watch black headed or squacco herons, malachite kingfishers and fish eagles (these among many other birds) going about their daily business but some time in the late 1970's it was filled in and a motorway was built over it. What I will say in the authorities defence is that with it gone so were the nightly plagues of mosquitoes that plagued the factories at that end of town. But! I still missed my bird watching.

Between Vereeniging and Vanderbijlpark there used to be a vlei. I stopped at the side of the road many times to watch black headed or squacco herons, malachite kingfishers and fish eagles (these among many other birds) going about their daily business but some time in the late 1970's it was filled in and a motorway was built over it. What I will say in the authorities defence is that with it gone so were the nightly plagues of mosquitoes that plagued the factories at that end of town. But! I still missed my bird watching.

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on September 30, 2020, 11:09 pmAfter reading the news about South African Airways today I decided to post this short piece that I wrote when they kicked my old friend the Jumbo Jet out.

After reading the news about South African Airways today I decided to post this short piece that I wrote when they kicked my old friend the Jumbo Jet out.

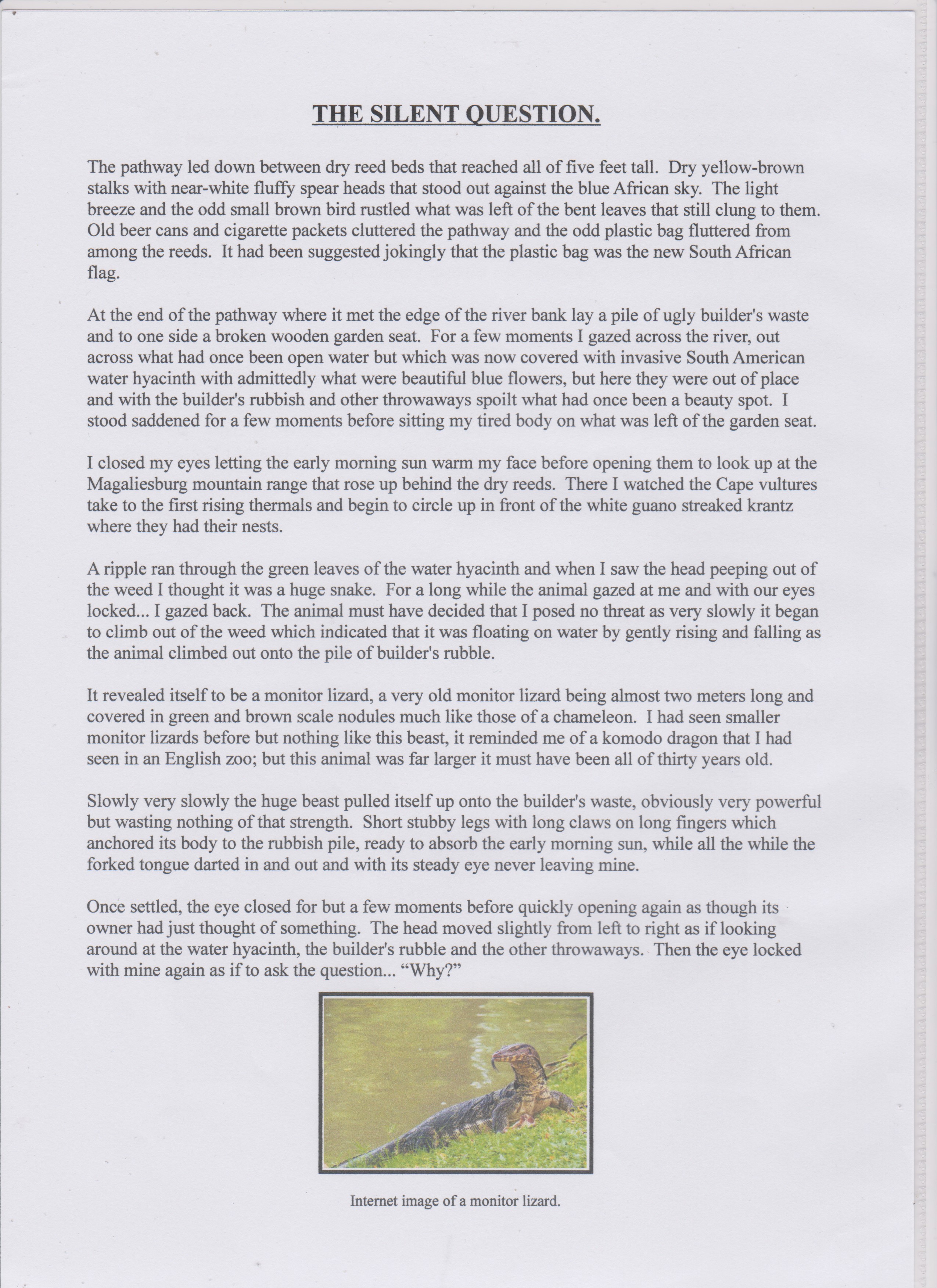

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on October 1, 2020, 6:12 amA few kilometres from Hartbeesport Dam.

A few kilometres from Hartbeesport Dam.

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on October 2, 2020, 12:05 amIn the Free State.

In the Free State.

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on October 2, 2020, 9:17 pmSomewhere in the Okavango Delta.

Somewhere in the Okavango Delta.

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on October 3, 2020, 11:35 pmA bushman's story?

A bushman's story?

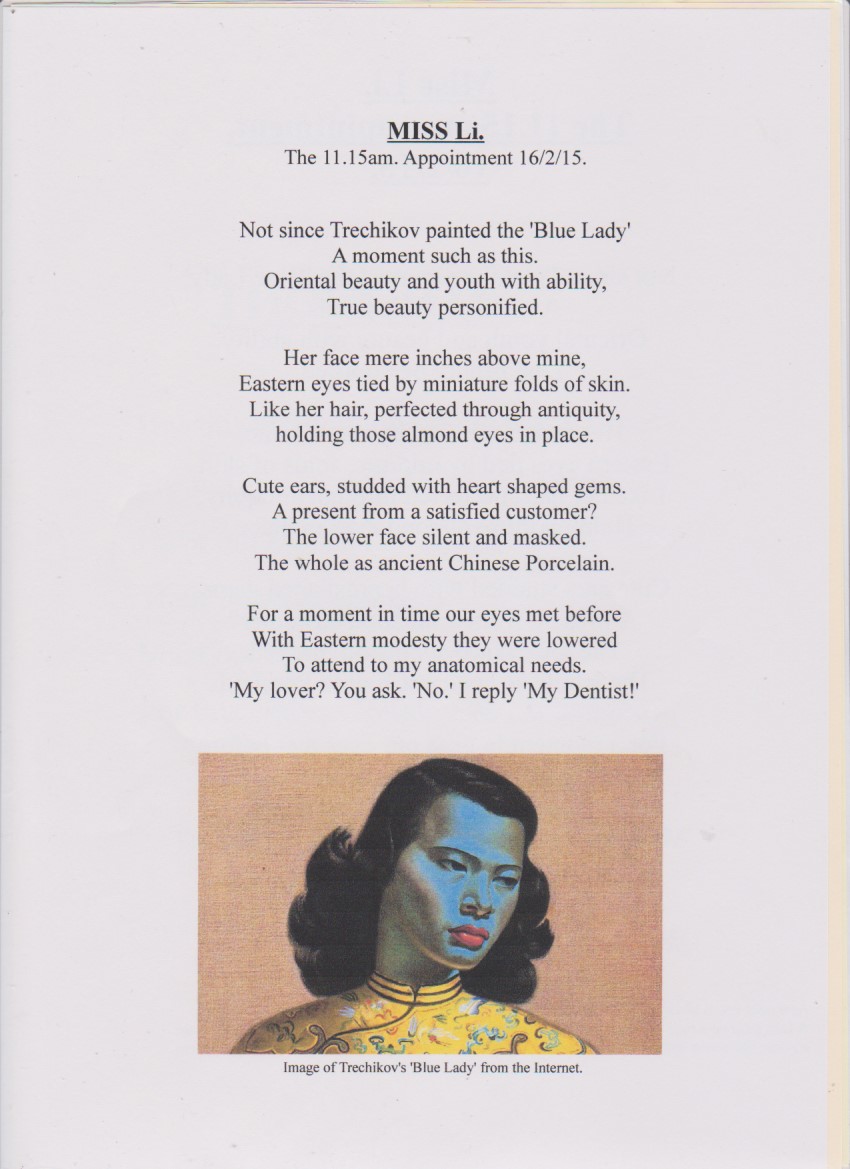

Uploaded files:Quote from Jamie Smith on October 5, 2020, 12:44 amI believe the Artist Vladimir Tretchikoff lived in Cape Town.

I believe the Artist Vladimir Tretchikoff lived in Cape Town.

Uploaded files:

Quote from Jamie Smith on October 7, 2020, 1:43 amJust another African 'Tall Story' or is it?

Just another African 'Tall Story' or is it?

Uploaded files:Quote from Steve on October 7, 2020, 10:01 amTretchikoff, well there's a blast from the past.

Chinese Girl (popularly known as "The Green Lady") is a 1952 painting by Vladimir Tretchikoff, a white Russian emigre who lived in Cape Town.

Tretchikoff's "Green Lady" hung in the lounge of my parents house in Pinelands. They had bought it at the same time as the spindly-legged Sixties furniture which my Mom proudly called her "Fruit Salad Lounge Suite". Every piece was a different shade of watermelon pink and green, apricot and peach. It was accompanied by a new, only marginally stereo Bush radiogram in an equally modern cabinet. These things co-existed alongside the sentimental clutter of my parents' lives, WW1 trench art brass shell cases that had been engraved by my grandfather, an art deco green rabbit with a chipped ear, a mantelpiece clock of indeterminate 1920s design and several Victorian brass candlesticks. The Green Lady, framed in a stoutly functional off-white frame, hung above the fireplace, lording it over this mish-mash, respendently mysterious, beautiful, exotic and intriguing.

This image reminds me once again of growing up in Pinelands during the Sixties. While there was much that was wonderful about being unconsciously young, privileged and white in Cape Town at that time, it was accompanied by a slowly awakening sense of horror about just how awful our society was. If we questioned the nature of it, the half-dead older generation replied that we were not old enough to understand the sacrifice they had made on our behalf, fighting wars to keep us free, lord and master in a country that historically had denied liberty and human rights to all its people. While I was a serious child, I could not expressed these thoughts then. All I knew was that South African society was rotten to the core, based on cruelty enforced by brutality, on an inequality that defined people's lives by the colour of their skin. Yet there, hanging in our living room, was the most superior brown and blue-skinned creature, the most desirable woman that I and many other white kids had ever seen.

At that time, many of my Pinelands friends' homes displayed a Tretchikoff print, invariably "The Green Lady", in their lounge. (It was never a loving room, then!) Perhaps this local commercial success was understandable. At one time Tretchikoff had been more successful in the USA than Picasso whom he had outsold. He occassionally visited our next door neighbour in Camp Road. I didn't realise it then but our neighbour was a know-all, a name-dropper and a bully who lusted after my Mom. When I was in high school he paid me more money to water his garden than I earned in my first proper job. This probably contributed in some way to my lifelong indifference to the importance of money as a major motivational factor in my life. One hot summer's day Tretchikoff parked his Porsche on the grass verge outside our house. My Mom spied him doing so from behind the net curtains in my sister's bedroom. Back then, net curtains were the Sixties equivalent of today's surveillance camera systems.

"Stephen, she commanded, "go and tell that awful Mr Tretchikoff not to park his sports car on our grass."

"Aaagh, ma..." I resisted. I was never going to tell the master of popular culture, perhaps the most commercially successful artist of his generation, to please be aware of my mother's middle-class sensitivities.

I was a callow boy and he was a famous man. I was under his spell. He had made me a slave to the beauty of the enigmatic Eurasian women he painted. Perhaps this contributed to my attraction to Suzie, the petite half-Javanese Coloured beauty who was our servant at that time. My Mom had taken her on from another family after she fell pregnant and was fired for being an unmarried embarrassment that needed to be explained. Sadly Suzie had had her perfectly fine, porcelain white front teeth removed so she "could kiss better". I never did kiss her but wish I had done so now. And more. If only.... what might have been.... how different I might have been, hey? I liked Suzie because she was fun. We would sit together after school on wet afternoons and read her Chunky Charlie comics and Marmaduke cartoons. Together we shared the equality of innocent laughter listening to my Searchers LP, the one she would borrow and ruin. But I never danced with her. Boy, I bet she could dance!

"Sweets for my sweet, sugar for my honey

Your first sweet kiss thrilled me so

Sweets for my sweet, sugar for my honey

I'll never ever let you go…".I don't know what happened to Suzie or why. She was a princess who didn't work hard enough for my Mom.

Tretchkoff's Green Lady bought into our lives the strongest statement about other lives lived many times more colourfully and exotically than anything learned in Pinelands High Scool, the Methodist Church and from the National Party. In Cape Town in the Sixties there was no swinging vibrant, colourful indigenous white or black cultural revolution. A visiting American described Cape Town as "a third rate cemetery in New York with the lights switched out!" It was exactly that! Our white youth culture came from Britain, most essentially a dark and dingy place in Liverpool called The Cavern. We were shadow people in the sunshine, hidden in the grey drabness Britain exported to Africa. Tretchikoff's rich colours and the detail he painted into a piece of brocade, a drop of water, a flower or a jewel, brown skin painted in blue or green or red, elevated me to a point where I could began to glimpse the splendour of another life not lived behind stuffy, never dusty made-in-Manchester net curtains of up-tight South Africans in suburbs zoned for "Whites Only".

Over the years I developed some pretensions to knowing a thing-or-two about art after religiously applying myself to reading Robert Hughes in Time magazine every week. When I was working for Pink Software in Johannesburg in the mid-Eighties the strength of my faux snobisme gained me access to the private art gallery of the Annegarns, parents of the company's marketing director. Eric's father was an industrialist who had made a fortune and spent much of it buying the work of leading South African artists. Eric's wife Bev took me to see the collection which was housed in a room about the size of my current house. Immediately on entering I saw at a glance a full and fabulous spectrum of white South African art, everything from Baines to Boonzaaier, Pierneef and Stern. It probably included works by black artists too. It was incredible, unbelievable, breath-taking. But there, down at the far end, was what was clearly a Tretchikoff. I couldn't help but blurt out to Bev, and I still do not understand why I did,"It's amazing", I said "but why on earth have you spoilt it with that Tretchikoff print." She laughed. "Go and have a closer look". It was the real thing.

Tretchikoff, well there's a blast from the past.

Chinese Girl (popularly known as "The Green Lady") is a 1952 painting by Vladimir Tretchikoff, a white Russian emigre who lived in Cape Town.

Tretchikoff's "Green Lady" hung in the lounge of my parents house in Pinelands. They had bought it at the same time as the spindly-legged Sixties furniture which my Mom proudly called her "Fruit Salad Lounge Suite". Every piece was a different shade of watermelon pink and green, apricot and peach. It was accompanied by a new, only marginally stereo Bush radiogram in an equally modern cabinet. These things co-existed alongside the sentimental clutter of my parents' lives, WW1 trench art brass shell cases that had been engraved by my grandfather, an art deco green rabbit with a chipped ear, a mantelpiece clock of indeterminate 1920s design and several Victorian brass candlesticks. The Green Lady, framed in a stoutly functional off-white frame, hung above the fireplace, lording it over this mish-mash, respendently mysterious, beautiful, exotic and intriguing.

This image reminds me once again of growing up in Pinelands during the Sixties. While there was much that was wonderful about being unconsciously young, privileged and white in Cape Town at that time, it was accompanied by a slowly awakening sense of horror about just how awful our society was. If we questioned the nature of it, the half-dead older generation replied that we were not old enough to understand the sacrifice they had made on our behalf, fighting wars to keep us free, lord and master in a country that historically had denied liberty and human rights to all its people. While I was a serious child, I could not expressed these thoughts then. All I knew was that South African society was rotten to the core, based on cruelty enforced by brutality, on an inequality that defined people's lives by the colour of their skin. Yet there, hanging in our living room, was the most superior brown and blue-skinned creature, the most desirable woman that I and many other white kids had ever seen.

At that time, many of my Pinelands friends' homes displayed a Tretchikoff print, invariably "The Green Lady", in their lounge. (It was never a loving room, then!) Perhaps this local commercial success was understandable. At one time Tretchikoff had been more successful in the USA than Picasso whom he had outsold. He occassionally visited our next door neighbour in Camp Road. I didn't realise it then but our neighbour was a know-all, a name-dropper and a bully who lusted after my Mom. When I was in high school he paid me more money to water his garden than I earned in my first proper job. This probably contributed in some way to my lifelong indifference to the importance of money as a major motivational factor in my life. One hot summer's day Tretchikoff parked his Porsche on the grass verge outside our house. My Mom spied him doing so from behind the net curtains in my sister's bedroom. Back then, net curtains were the Sixties equivalent of today's surveillance camera systems.

"Stephen, she commanded, "go and tell that awful Mr Tretchikoff not to park his sports car on our grass."

"Aaagh, ma..." I resisted. I was never going to tell the master of popular culture, perhaps the most commercially successful artist of his generation, to please be aware of my mother's middle-class sensitivities.

I was a callow boy and he was a famous man. I was under his spell. He had made me a slave to the beauty of the enigmatic Eurasian women he painted. Perhaps this contributed to my attraction to Suzie, the petite half-Javanese Coloured beauty who was our servant at that time. My Mom had taken her on from another family after she fell pregnant and was fired for being an unmarried embarrassment that needed to be explained. Sadly Suzie had had her perfectly fine, porcelain white front teeth removed so she "could kiss better". I never did kiss her but wish I had done so now. And more. If only.... what might have been.... how different I might have been, hey? I liked Suzie because she was fun. We would sit together after school on wet afternoons and read her Chunky Charlie comics and Marmaduke cartoons. Together we shared the equality of innocent laughter listening to my Searchers LP, the one she would borrow and ruin. But I never danced with her. Boy, I bet she could dance!

"Sweets for my sweet, sugar for my honey

Your first sweet kiss thrilled me so

Sweets for my sweet, sugar for my honey

I'll never ever let you go…".

I don't know what happened to Suzie or why. She was a princess who didn't work hard enough for my Mom.

Tretchkoff's Green Lady bought into our lives the strongest statement about other lives lived many times more colourfully and exotically than anything learned in Pinelands High Scool, the Methodist Church and from the National Party. In Cape Town in the Sixties there was no swinging vibrant, colourful indigenous white or black cultural revolution. A visiting American described Cape Town as "a third rate cemetery in New York with the lights switched out!" It was exactly that! Our white youth culture came from Britain, most essentially a dark and dingy place in Liverpool called The Cavern. We were shadow people in the sunshine, hidden in the grey drabness Britain exported to Africa. Tretchikoff's rich colours and the detail he painted into a piece of brocade, a drop of water, a flower or a jewel, brown skin painted in blue or green or red, elevated me to a point where I could began to glimpse the splendour of another life not lived behind stuffy, never dusty made-in-Manchester net curtains of up-tight South Africans in suburbs zoned for "Whites Only".

Over the years I developed some pretensions to knowing a thing-or-two about art after religiously applying myself to reading Robert Hughes in Time magazine every week. When I was working for Pink Software in Johannesburg in the mid-Eighties the strength of my faux snobisme gained me access to the private art gallery of the Annegarns, parents of the company's marketing director. Eric's father was an industrialist who had made a fortune and spent much of it buying the work of leading South African artists. Eric's wife Bev took me to see the collection which was housed in a room about the size of my current house. Immediately on entering I saw at a glance a full and fabulous spectrum of white South African art, everything from Baines to Boonzaaier, Pierneef and Stern. It probably included works by black artists too. It was incredible, unbelievable, breath-taking. But there, down at the far end, was what was clearly a Tretchikoff. I couldn't help but blurt out to Bev, and I still do not understand why I did,"It's amazing", I said "but why on earth have you spoilt it with that Tretchikoff print." She laughed. "Go and have a closer look". It was the real thing.